Fifty years ago this summer, France was between and betwixt events of lasting import. The wounds from the Algerian War — ended just four years earlier — still bled, while the tinder to the “events of May 1968” — namely the student rebellion and worker strikes that nearly pushed Charles de Gaulle from power — was still gathering. Echoes of both events can now be heard in the explosions of terrorist bombs and chants of protesting workers and students in Paris.

Given the lasting and seismic nature of these events, the impact that same summer of what film critic Pauline Kael called the “most efficacious make-out movie of the swinging sixties” amounts to a hill of beans. And yet, with apologies to Virginia Woolf, on or about July 1966, human character changed. Or, at least, my character changed when Claude Lelouch’s Un homme et une femme opened that month in the US.

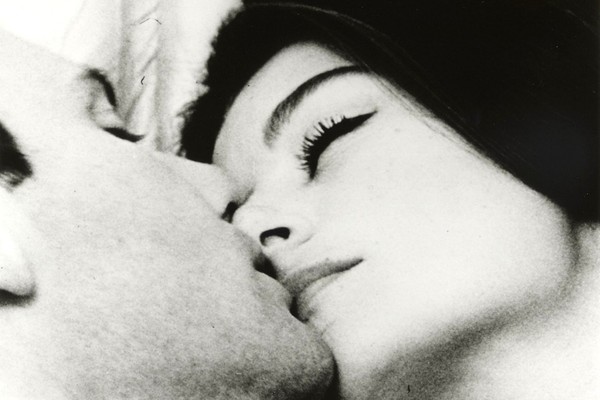

Though it was a few years later that, as a high school student, I first saw A Man and a Woman, the images and music had already buried themselves in my mind. The white-bordered poster framing a pink-hued shot of Jean-Louis Trintignant and Anouk Aimée hung in my brother’s bedroom. Their eyes are closed, which struck my barely teen self as perfectly normal. But their lips are also closed. Only recently introduced to the theory, not the practice, of French kissing, I should have thought this pose perfectly oxymoronic.

And yet, with apologies to Ludwig Wittgenstein, I suspect there are others who have, along with me, been held captive by this one picture and cannot get outside it. Dimly but deeply, I knew the image was right — as right as anything ever could be. This was France, a world of grace and gravity I wanted to be part of. It is no less right today, as is Francis Lai’s theme song I waited to hear on my transistor radio. The melody is short and sharp, while the lyrics are monosyllabic. Carried by two voices — a man and woman’s, bien sûr — it is a lazy cascade of ba-da-ba-da-da-da-da-da’s. Coasting along for less than three minutes, the song is mostly unencumbered with actual words. How could it be otherwise for lips that are closed?

In fact, the wordless song is perfect for a film also mostly unburdened with words. There are, to be sure, bits and pieces of conversation, but were they to disappear entirely the film would remain whole. The film doesn’t do much more than riff on the poster, images succeeding one another sometimes in black and white, sometimes in color. (The reason, Lelouch later revealed, was economic, not aesthetic: by the end of the filming, he was nearly broke.) A tracking shot of a Mustang race car fishtailing on a snowy road, or purring slowly along a beach; a prolonged shot of Trintignant behind the wheel of the Mustang, partly obscured by wipers sweeping away the rain, or a shot of Aimée watching her young daughter, partly obscured by her hand sweeping away her hair; a glimpse of them exchanging glimpses, or a glimpse of them exchanging kisses that are somehow both passionate and chaste.

Many of us, famously, learned how to kiss from the movies. While I should have taken better notes on that subject, the real lesson I took from A Man and a Woman was something different. I learned how we fall in love. A film carves an image in our minds, an image that shapes our responses to the world and to others. This is, with apologies to Virgil, the Dido response. Aeneas astonishes the Carthaginian queen by appearing, out of a mist, inside a temple she is building to Juno. The temple, it turns out, is version of a cinema house: carved along its walls are many scenes — what Virgil calls “mere image” — of the Trojan War. As Aeneas “feasts his eyes” on these moving pictures, he learns what Dido already knows: he’s the star in a DeMillian epic for which Dido has had a front row seat.

In short, Dido was already falling for Aeneas before they ever met. On that fateful day at the Carthage Cinémathèque, when she was in free fall, all he did was catch her, only to drop her a short time later in order to found Rome. When I first saw A Man and a Woman at the Bleeker Street Cinema in the early 70s, I was caught by an image of France. (That this happened to be the image of a woman was only natural: the personification of France, after all, is Marianne.) I was still falling a few years later when, at a youth hostel, a (French) woman caught me. She dropped me a few years later in order to move to Rome (not at the command of a Latin god, but at the invitation of an Italian biochemist.)

Since that abrupt ending, since becoming an historian of France and having a more complex understanding of the country — and, I hope, myself — than I did as an impressionable teen, I am still enthralled by my particular picture of France, but no longer captive.

Captivation is what cinema aims for, but in life, as we all know, it can be problematic. I keep returning to Aimée and Trintignant’s faces, graced by impossibly high cheekbones and alabaster skin, wreathed in cigarette smoke, even as I know that for others, the picture is different: Paris boulevards wreathed in smoke from tear gas grenades or a flaming police car. For others still, the picture is of an anniversary meal at a fine Paris restaurant, slowly wreathed in cigarette smoke from a neighboring table.

Of course, the sort of captivity I felt gazing at the poster is not exclusive to awkward American teenagers. It may well be that the images etched in Claude Lelouch’s mind as a Jewish child, hidden by his mother in movie houses to evade police dragnets in occupied Paris, shaped a film where faces, not words, express fear and doubt as well as hope and certainty. What images may have been pressed onto the imagination of the young Aimée, née Nicole Dreyfus, during the war? Given a false identity and hidden by her Jewish father in the French countryside, I now wonder how these “pictures” informed her performance as a widow traumatized by the death of her husband.

In the end, a picture can free us as well as capture us. When I recently watched A Man and a Woman for the first time since my Bleeker Street epiphany, I realized I had forgotten the film’s end. After Aimée and Trintignant are reunited at a train station, Lelouch does not give us a fade of embracing lovers. Instead, he gives us a freeze frame, catching Aimée and Trintignant between and betwixt. I stare hard at her expression, one of pain and relief, and despite the misbegotten sequel Lelouch made 20 years later, I still no more know what the future holds for her than she does. It is as open now as it was a half-century ago on Bleeker Street.