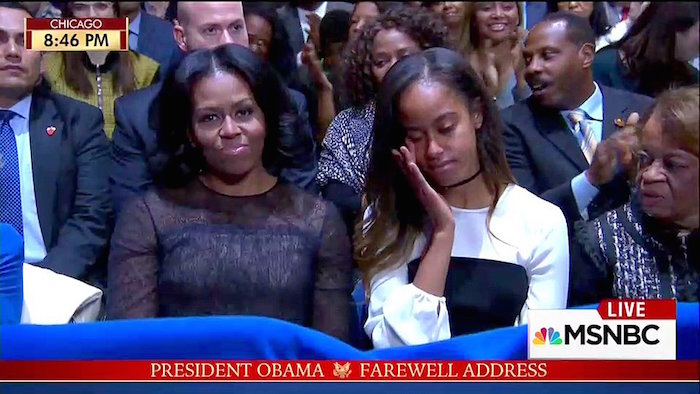

Donald Trump has been the president of the United States for just over a week. Though that week has had, within it, some radiant moments of hopefulness (mainly, the women’s march), what follows is not hopeful. What follows is living after the end of hope, a moment marked, I think, by Malia Obama’s tears at our previous president’s Farewell Address.

Malia’s was a hard cry to watch — for me and I am sure for many — because it was a cry that we know intimately: the public-private kind of breakdown that one usually has for the first time in the late teens or early 20s (Malia is 18.) The kind of cry you might have on a bus, listening to music, looking out the window and letting your mind wander, only to realize, after the tears have already come, that you are not invisible to your fellow passengers. It was a cry caught between the loneliness of the window and the humiliation of the aisle.

Sylvia Plath writes about this kind of cry in The Bell Jar, when the young narrator confides, “I knew that if anybody spoke to me or looked at me too closely the tears would fly out of my eyes and the sobs would fly out of my throat and I’d cry for a week.” It was the kind of cry that is about a lot of things that happened before only to become sharpened to a point, intensified, irrevocably, embarrassingly, by the sound of a parent’s voice picking up the phone.

But this is important: it was not Barack’s mention of his family that made Malia cry. It was not, as one headline reported, “Malia Brought to Tears By Obama’s Message to Michelle.” When the camera turned to Malia as Barack said the word “Michelle,” Malia’s eyes were already rimmed in tears. She had been crying. The footage that has now been so discussed and reposted was not of a daughter suddenly choked up by her powerful father’s tender sentiments towards his family. These were the tears of a young, female citizen of color on the precipice of a terrifying political era who received a call from her father. A young woman on the biggest bus in the world, realizing that her private moment is suddenly very public.

In Tom Lutz’s The Natural and Cultural History of Tears, he cites the 18th-century distinction between physical crying and moral weeping. Physical crying is the sort that might be produced by rhetoric or a sentimental performance. Moral weeping comes from the deepest recesses of the heart. This was undoubtedly moral weeping, as we can see acknowledged by her grandmother, who unmistakably whispered to her, face tensed with concern, Are you all right? Michelle, too, seemed to acknowledge the depth of Malia’s cry with a smile that insisted her daughter mirror her, a smile tinged with the strength and pain of someone older, someone who has been devastated before.

Malia’s tears are a moment of profoundly mythic national iconography on level with JFK Jr.’s pathetic salute. And just as tragic as a child forced into the rituals of militarism at his father’s funeral is a young woman forced to smile in the face of an unthinkable political and social reality, rife with outright racism and brutal misogyny.

The speech that made Malia cry covered all sorts of ground, quoting everyone’s fantasy father, Atticus Finch, early on, and ending with a zinger from our collective national father George Washington, with many other bits and pieces of founding-father prose sprinkled throughout. At times, Obama verged with Polonius-like tendency toward aphorism. Polonius, you remember, is the father in Hamlet who sends his son off to school in France with the wise words, “This above all: to thine own self be true” — a sentiment reiterated by Obama throughout the speech in many different guises. And, finally, he urged us: “Ultimately, that’s what our democracy demands. It needs you.” But who is this “you”? And have we had enough time to find out?

Here is why Polonius’s oft-quoted advice to Laertes is meaningless: how can someone who has yet to really learn anything know what the nature of his or her self is? The self is forged in the smithy of experience. To tell a teenager to follow the self as a guide is to hand over a blank chart of latitudes and longitudes and ask them to locate a foreign country.

To someone who is over 50 (like Barack Obama) or 60 or 70, history has produced (as a fatherly Obama reminded us) many ups and downs. Yet to someone who can only really remember the eight years of his presidency, to someone who is just 18, there is only the Obama administration and the administration that will follow it. There is only an idealistic hope for the future and a rage-filled call to return to the past.

The farewell speech as a whole was very forward-thinking: here is what we can do, here is how things will play out. He made predictions by way of frequently referencing our children, painting a picture of brown kids growing up to be the majority of the workforce, reminding us that everyone’s children are “just as curious and hopeful and worthy of love as our own.” But to those Americans who are young themselves (or, as Obama added, just “young at heart”), those without children on whom to project fantasies of unfulfilled promise, and those on whose shoulders the future (that an older man, a retiring president, can wax lyrically about) rests, the future does not look so bright.

The logo of the Obama campaign was a road stretching into a sun-lit distance. Hillary’s logo was an arrow pointing forward. But Hillary did not win. President Trump didn’t really have a graphic campaign logo unless you count his initial penetrating Pence’s, which inconsistently made the rounds. Instead, he had a slogan that asked us to go back. The future was yours, this outcome seems to say to an 18-year-old woman of color, now it is ours again.

Perhaps we can see her father’s speech in Malia’s eyes more clearly if we place it in dialogue with the speech her mother made in Manchester, NH, on October 13th, in which the then first lady responded to the breaking revelation of Trump’s notorious, sexually violent comments to Billy Bush. “I feel it so personally,” Michelle said of Trump’s words, “and I’m sure that many of you do, too, particularly the women … It is cruel … it hurts.” She asked, “If all of this is painful to us as grown women, what do you think this is doing to our children?” Near tears herself, she urged us to “[i]magine waking up on November the 9th and looking into the eyes of your daughter”

And there she was, on January 10th, sitting beside her own daughter, indeed forcing her to smile with her as her husband urged the nation to accept the outcome of the election as a part of our democratic process. To think about the future beyond the future, to be true to her own self. To a self under attack. To be true in a time when it is unclear what truth is.

Here is an aphorism I do find meaningful: Horace Walpole wrote to Horace Mann (from one Horace to another) “this world is a comedy to those that think, a tragedy to those that feel.”

The recent past has not, for the nation, been a time of thinking. This election was run and won on hot-headed anger, fueled by emotion rather than evidence or policy. Since Trump’s campaign began, there has been talk of entering a “post-truth” era. Indeed, “post-truth” was the Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year for 2016. Kellyanne Conway has also given us the “alternative fact,” the truth determined by the reality one feels—not the reality of science or critical inquiry.

For the past two months, I have been trying to stop feeling tragic and think my way to comedy. Or at least to follow Michelle’s lead and muster a tight-lipped smile. But in the haze of post-truth culture, rage culture, rape culture, hate culture, terror culture, I’m finding it hard to laugh. The kind of catharsis we need right now cannot come from a late night comedian or a political sketch. To watch Malia was to inhabit the world as tragedy. Was to stubbornly feel when we are being asked to think, to collectively mourn what has happened here.

There is another aphorism I like, which comes from Karl Marx and uses the same generic strategy as Walpole’s: “history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.” Marx is referring to Napoleon’s nephew’s reign, trying to explain the riddle that Obama, too, posed: why do we seem to move a bit forward politically only to take such a huge step back? Marx goes on to write:

“The tradition of all the generations of the dead weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem involved in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something that has never before existed, it is precisely in such periods of revolutionary crisis that they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow names, battle cries, and costumes from them in order to act out the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language.”

And so Obama’s speech was a curtain call on the promise of hope and change. The next act is the revival of Cold War paranoia and McCarthyism, “the golden era” of America before civil rights, before second-wave feminism.

Some time in the very recent past, Malia Obama woke up for the very last time in her bedroom in the White House — a house, her parents were fond of reminding the nation, that was built by slaves. And as she left with her family, the clock rewound, the future arrived as a version of the past that she and others like her have already been written out of. Perhaps we can grow to see it as farce, but it will take a lot of thinking to be able to laugh.