Earlier this month, when USC announced that it might seek its own legal action against Lori Loughlin and her husband Mossimo Gianulli, you could almost hear the collective groan of pleasure ripple across the media. On social media, the reaction was every bit as enraged, offended, and self-righteous as you might imagine. But why?

One of the greatest social groundswells changing our public culture today is a move away from punitive reactionism in our judicial system and towards a view that sees a whole person who has been convicted of a crime — and not simply a “criminal” who’s lost the potential for personhood. This trend is a deep and important one, as it predicates not only how we view crime and criminality but also how we understand our society.

Increasingly, we’re becoming conscious of the real consequences of the kind of justice system we choose to embrace — whether it’s one that makes us cruel, hard-hearted, and given to zealous excess or compassionate, confident, willing to forgive, and hopeful of a better future.

This makes the recent dovetailing rounds of schadenfreude concerning Loughlin so much more perplexing. There’s no doubt that what Loughlin has been accused of is wrong. The perversion of our academic system is a deadly serious matter, especially when the effect is to tilt the playing field in the favor of people who already have nearly every advantage imaginable (except, maybe, that of common sense).

The story, as we tell it, includes clear implications of greed, vanity, arrogance, and a self-serving abasement of higher education. Loughlin’s unrepentant public stance, her absence of even nominal remorse, has only exacerbated things.

And that may all be true. But here’s the thing: is that really cause for delight? Is it not a moment when we can take our oft-hashtagged feelings of empathy and compassion and put them to use, not in spite of the obnoxiousness of this particular case but because of it?

Looking through a slightly different lens, we might see Loughlin and Gianulli as two parents who wanted the very best for their children — and did something they shouldn’t have in order to secure it. The saints among us excepted, it’s an utterly human impulse which we all carry inside ourselves.

In thinking and talking about America’s justice and penal systems, we’re frequently told stories about people who committed terrible crimes — crimes that destroyed lives and families — but who, with a second chance and enormous effort, manage to redeem themselves. One might argue that these stories of redemption often (but not always) feature men or women who have served their time and paid their dues. In the case of Loughlin and Gianulli, who haven’t even been convicted, it’s entirely imaginable they’ll be found innocent. And, even if found guilty, shouldn’t we offer them a chance at redemption?

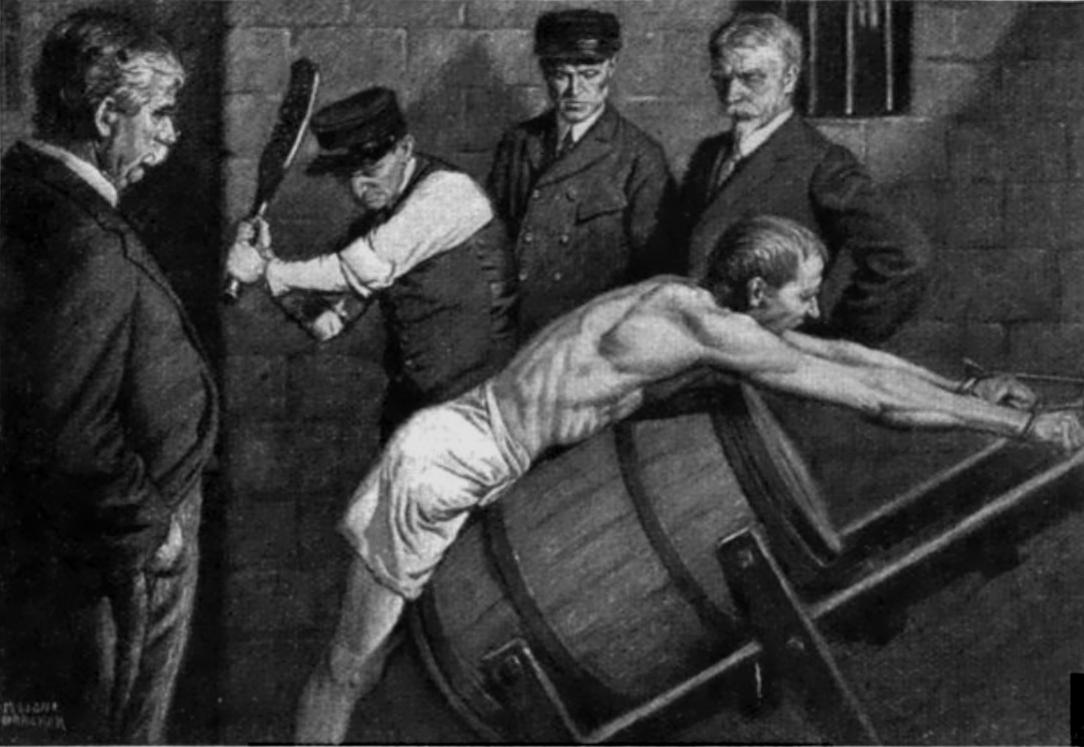

But the real point is a deeper one. Schadenfreude is a bit like torture: it leaves a wound on those who commit it by making them the kind of person that profits from someone else’s pain. Lori Loughlin and Mossimo Gianulli might not have a lot to teach us about how to live our lives. But by looking at our own reactions to their plight — and yes, whatever the causes might be, it’s a plight — we can learn something about ourselves.

The media may have pinned the scarlet letter on Loughlin’s breast, and social media pushed her onto the scaffold, but it’s we who serve as the jeering crowd. It’s for our benefit that a couple whose alleged crimes do not have a clear victim now face the prospect of sitting in prison, while white-collar criminals whose actions immiserate thousands regularly get off with a rap on the knuckles, or nothing at all.

More importantly, though, when the trap door finally drops and the condemned swing, we’ll be left needing to satisfy our bottomless hunger to demonstrate that we’re better, more righteous, and less fallible than the people who were once held up as paragons.

The question we each need to ask is: is that the kind of person I want to be? Is this the culture in which we want to live? The answer, I hope, is no.