By John Shannon

In 1939 Henry Miller published a humorous autobiographical sketch in the forgotten pacifist journal Phoenix (Vol. 2, No 1) called “Via Dieppe-New Haven,” chronicling his failed 1935 attempt to ferry himself over the Channel to visit England. Having little cash on hand, he was sent straight back.

In 1973, knowing nothing about that illustrious attempted journey, I was living without much cash on hand in Southern England, also writing. I regularly ferried the exact reverse of Miller’s trip, from nearby New Haven to Dieppe, in order to stay in France a day or two, allay the Foreign Office’s suspicion, and then renew my two-month tourist visa with a big innocent smile. That’s the first irony.

I’ve always resisted writing anything like autobiography, because who the hell am I? But during that special year, the accidental influences, the social changes going on, and sheer dumb luck dropped me among people, issues, and books worth talking about.

In case you’re getting impatient, the books in question are by the great British art critic, essayist and novelist John Berger, who will turn 90 in November of this year. By my count Berger has written 35 books of essays, 11 novels, five screenplays, and several plays and collections of poetry. At least three of these are modern classics, picking apart the Swiss watch of the world to show where the springs are hidden. These are A Fortunate Man (1967), Ways of Seeing (1972), and A Seventh Man (1975), books that radically changed my life. Oh, yes, radically. But wait a bit. First, more ironies.

“He was in his mid thirties: at that time of life when, instead of being spontaneously oneself, as in one’s twenties, it is necessary, in order to remain honest, to confront oneself and judge from a second position.”

— John Berger, A Fortunate Man

From 1968 to 1970, I taught school in Africa for the Peace Corps, and on school holiday I fell in love (well, sort of) with a beautiful young blonde I met in what was then white-ruled Rhodesia. Later, on my way home through England, we met again as she was starting med school at Sussex University near Brighton.

Let’s call her Jennifer. Jennifer and I corresponded warmly on and off for years while I saved up enough money at meaningless writing jobs back home to escape Nixon’s America for good. We agreed that I would come to live with her. I saved, I scrimped, I borrowed — and bought a cheap one-way charter flight. But the day I showed up in Brighton I discovered what she’d neglected to tell me: she’d fallen madly in love with a charismatic German student named — let’s call him Rainer. That may not be an irony, but it was a shock. I had sold off and dismantled my life in America.

Rainer had been a student of Jürgen Habermas, the last of the great Frankfurt School critical theorists and post-structural Marxists. Rainer was also one of the leaders of the 1968 student uprisings in Frankfurt, a magnetic character, and a superb writer in both English and German (he ended up with Der Spiegel.) Within a day of my arrival Rainer and I were close friends and collaborating on translating Bertold Brecht’s allegorical Me-ti stories, humorous episodes that disguise Brecht’s practical non-dogmatic Marxism. (They weren’t in fact fully translated into English until 2016.)

Rainer and I recruited another student, call him Mike, and the three of us found a derelict nineteenth-century farmworker house (“tied cottage” is the British term) a half-mile outside a tiny village north of Brighton named Ringmer. The farmer was happy to let us fix it up. We painted, plastered, hammered, and furnished it from the dump (“the tip”) and various rummage sales (“jumblies”). And then Rainer, who had his eye on another woman, decided not to let Jennifer move in with us. Now that qualifies as irony. For me, anyway.

Mike was from a political family, too. His oldest sister was deeply involved in anti-racist politics in Birmingham and a leader in the Militant stream within the Labour Party. She became an MP and eventually entered Tony Blair’s cabinet, but she split with him over Iraq, bless her. Her whole combative family spent many weekends around our bright red kitchen table in Ringmer, arguing politics. Her younger sister was even more radical. This is all foreshadowing, if you stick it out with me.

Left-wing politics were as prevalent in England in the early 1970s as drizzly grey skies. You couldn’t step out of any tube in London without a dozen radical newspapers being thrust at you. I’d grown up in San Pedro alongside the children of Communist longshoremen, so none of that put me off. But by then an elite college (Pomona) had wrung most of the political thought out of me.

What the hell, I thought. I sat down at my upstairs desk — a door on bricks — and dove back into politics. In addition to working on a novel and journalism, I read Marx’s Capital and took careful notes. (Calling it Das Kapital in America is just the Cold War way of making it seem strange and alien, believe me. It’s Capital in England, Le Capital in France.) Then I read more Marx, a bit of the Frankfurt School, plus Gramsci and the post-structural Marxists. We all argued day in, day out, and my inner political ice shelf began breaking up during thaws and then refreezing in new shapes.

“Vulnerability may have its own private causes, but it often reveals concisely what is wounding and damaging on a much larger scale.”

— John Berger, A Fortunate Man

The nub: As I started to situate myself within a new notion that social class can actually influence the way we see and think (it promotes a particular ideology, to be precise), a part of me rebelled. Way too crude, I thought. That famous Communist Manifesto doesn’t speak to me. “You have nothing to lose but your chains.” Hell, I’m not a proletarian waving a red banner. Brothers and sisters in manual labor, hell. (Though a few years later, back in America, I would choose to work in an industrial factory for two years. It’s okay, you can smirk.)

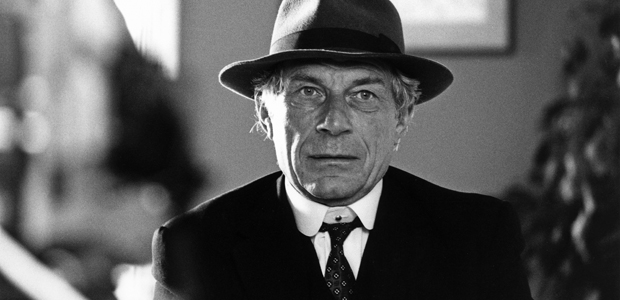

My inner American ice shelf was still largely intact in mid-1973 when I visited a friend in Brighton for a drink (probably Brendan Behan’s brother Brian, but that’s another story). He was preoccupied in his sitting room with a BBC TV show called Ways of Seeing. We didn’t have a telly out in Ringmer so I missed all of Monty Python, too! My eye caught on an almost lisping guy in a pointy disco collar who was talking about the hidden ideologies in advertising images that we don’t notice because we’re so overwhelmed by similar images.

“Who the hell is that?” I asked.

“John Berger, arsehole. Our only real radical thinker— except me, of course.”

You’ll soon know a lot more about John Berger, if the loving four-part documentary film by Tilda Swinton and others titled The Seasons in Quincy ever finds American distribution. It was a hit at the last Berlin Film Festival, but that means little in the States. PBS has never shown John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. It is, as far as I know, the only BBC show about art that was turned back at Ellis Island.

I immediately bought as many of John Berger’s books as I could find in Brighton. Berger has won a Booker Prize for a novel called G (1972) that I find quite odd but also fun and readable, despite the fact that “odd” has never been my thing in novels. But mostly he’s a stunning aphoristic essayist about art and our world. And he’s gone on writing his essays even after retreating four decades ago to the life of a peasant farmer in the middle of nowhere in France — in Quincy, pronounced “Keen-sy.” He has documented this life, too, in his novelesque trilogy Into Their Labors (1991), probably better known by the title of the first book, Pig Earth (1979). Yeah, geniuses get to go off into caves and do stuff like that.

Here’s my take on Berger’s most powerful books, in the order that they came at me:

1. Ways of Seeing. This is the one that crashed through my ice shelf for real. The most important thing it taught me is that critical theory and social analysis is not that crude Stalinist nonsense about tractors and heroes of labor. It’s a painstaking and scrupulous analysis of the assumptions that lie under the surface of our lives, and of the art that arises from it. For me this idea took off in essays 2 and 3, which concern artistic depictions of women and men. Berger talks about how men are usually shown in Western art in terms of what they can do to you or for you. Women, on the other hand, are forced to pose in terms of what can be done to them: “She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought as the success of her life.”

“Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Go ahead, Berger challenges, look at any famous painting of a nude woman — say, Goya’s The Naked Maja (1797-1800) — and imagine a man’s face on it: “Then notice the violence which that transformation does. Not to the image but to the assumptions of a likely viewer.”

I guess this insight has become almost a commonplace in feminist studies now, but 40-some years ago, it staggered me.

The next essay (No. 5), about how European oil painting reduced the world to things and materiality, was less affecting, but still convincing: “Oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects. Everything became exchangeable because everything became a commodity. […] What distinguishes oil painting from any other form of painting is its special ability to render the tangibility, the texture, the luster, the solidity of what it depicts. It defines the real as that which you can put your hands on.”

Finally, after another photo prelude, there’s the written version of the piece that caught my eye on the telly. Essay 7 is about advertising images. “No era before ours,” writes Berger, “has constructed such a dense assault of imagery on its citizens. “ Ads rarely tell you the advantages of a specific product (there probably aren’t any). They’re meant to make you envy the glamorous world you’re looking at, where handsome models are never unhappy and possess a VIP pass to everything. These images make us nebulously dissatisfied with who we are and subtly suggest that buying whatever commodity is shown will change it all. Buy and be!

(The TV version of Ways of Seeing is on YouTube, if you want to watch in small bites. You’ll get to see that embarrassing disco shirt.)

2. A Fortunate Man. Not the first Berger I read, but maybe the most powerful. It starts out as the tale of a compassionate country doctor in an isolated community in Gloucestershire near Wales. In the book he’s called Dr. John Sassall. I hear now that many medical schools in England make the it required reading.

Berger looks at specific examples from the doctor’s practice, some quite astonishing, but gently and gradually the focus shifts to unraveling the cultural and economic deprivations that have been visited upon the villagers he treats: “They have no examples to follow in which words clarify experience. […] The culturally deprived have far fewer ways of recognizing themselves. […] Their chief means of self-expression is consequently through action: this is one of the reasons why the English have so many ‘do-it-yourself’ hobbies.” The men speak to one-another endlessly about “a motor-car engine, a football match.” Some critics of Berger consider this attitude condescending, but I grew up in the American suburbs, with men wandering from open garage to garage on weekends, beer can in hand, discussing their “projects,” and I find it acutely perceptive.

Dr. Sassall is a “fortunate man” because he’s the village’s healer, their shaman, their personal witness, and, more importantly, because he’s been able to examine his own life and its pains as most of them cannot: “The privilege of being subtle is the distinction between the fortunate and the unfortunate.” Indeed, Berger’s analysis accounts for the anti-intellectualism of the working poor, which so many of us find so frustrating: “[A]ll theory seems to most of the local inhabitants to be the privilege and prerogative of distant policy-makers. The intellectual — and this is why they are so suspicious of him — seems to be part of the apparatus of the State.”

By the end, Berger’s book has taken a turn — one almost unnoticed, because he writes so artfully — toward an insightful deconstruction of Western Civilization.

In assessing Sassall, Berger says, “I do not claim to know what a human life is worth — the question cannot be answered by word but only by action, by the creation of a more human society. All that I do know is that our present society wastes and, by the slow draining process of enforced hypocrisy, empties most of the lives which it does not destroy.”

Dr. Sassall’s real name was Dr. John Eskell, and, alas, the human needs of the residents of St. Briavels, as well as his own inner needs, finally consumed him. At age 62 he killed himself by gun and was reportedly denied a cemetery plot in the village where he served as healer and witness for years.

3. A Seventh Man. Before the recent flood of Syrian war refugees to Europe, every “seventh man” doing manual labor in Germany or England, and every fourth in France, was a guest-worker, almost invariably from the shores of the Mediterranean. To put it crudely — Turks to Germany and North Africans to France.

The word “man” is basically accurate. Most left their wives and children at home, in their impoverished villages, waiting for their men to return with a tiny bit of saved capital. Sometimes enough to build a house or start a small business. At its most poignant, this is as little as the money needed to buy a home bathroom scale and set it up in the village square as “Your weight for a penny.”

A large portion of this book is theoretical, about how the Third World has been systematically “underdeveloped.” (It was the Cubans who decided that was a verb.) Most of Berger’s statistics and theory about globalization are dated now. But what remains moving is the impressionistic access he proposes to the thoughts and feelings of the bewildered migrants themselves, faced with an opaque world that sees them as inferior beings. Or doesn’t see them at all.

“Migrant workers, already living in the metropolis, have the habit of visiting the main railway station,” he writes. It’s a kind of magic connection with home, a place of activity where they are accepted, though only as spectators. They come “[t]o talk in groups there, to watch the trains come in, to receive first-hand news from their home, to anticipate the day when they will begin the return journey.” Berger takes us to the station’s exit, where a worker finds others “talking in his own language. The words of it are like foliage re-appearing on a tree after winter.”

A village butcher becomes a worker in a giant abattoir, slaughtering cattle so rapidly he nearly hallucinates: “[T]he flow of heads to be washed and hoofs to be shifted never ceased, he began to have the impression that the machines were multiplying the animals: that they took one and turned it into a hundred.” After work he wanders the city, a bit stunned: “[H]e became more and more conscious that there were no animals to be seen.” From the nature of the village to the artifice of the city — in a single leap.

Another worker tacks up photos of women around the bunk in his crowded rooming house, “a votive fresco of twenty women, nude and shameless. The prayer is that his own virility be one day recognized.” And everything he is and knows.

The book’s argument is this: “To see the experience of another, one must do more than dismantle and reassemble the world with him at its center. One must interrogate his situation to learn about that part of his experience which derives from the historical moment. What is being done to him, even with his own complicity, under the cover of normalcy?”

These three books of John Berger examine the ideologies hidden in the ways we perceive the world, in the ways we value or can’t value human lives, and what our system does to those from the third world without us even thinking about it. John Berger made me think about that for the rest of my life.

John Shannon is the author of the Jack Liffey mystery novels that are based on Los Angeles ethnic and social history, and several other novels. His website is: jackliffey.com