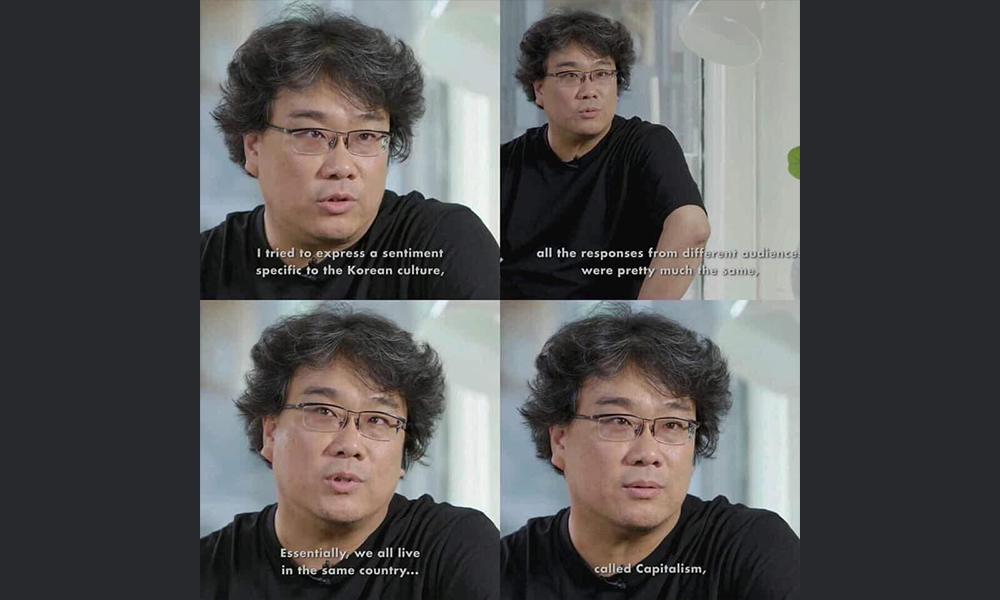

In a viral meme following Parasite’s sweep at the Oscars in four major categories (Best Picture, Best Director, International Film, and Original Screenplay), director Bong Joon-ho explains the runaway success of the film with an axiom: “Essentially, we all live in the same country called Capitalism.”

Made by the Insta-commentariat, the meme captures the essence of the film’s transnational critique of predatory capitalism, which is paradoxically everywhere and nowhere. In this fictional country, what you see is not what you get unless or until you understand a kind of pervasive and parasitic interdependency as its structure of feeling. It is seemingly innocuous and yet exploitative, and at once life sucking and life giving. As a kind of ludic auto-critique, the repetition of Bong’s deadpan close-ups mimics the hypnotic proliferation of its axiomatic message, and extends the film’s dazzling anti-capitalist and anti-racist sentiments. To say it has the effect of engaging but also exceeding the Koreanness of those sentiments is to say the least.

The Bong talking head further explains, “all of the responses from different audiences [of the film] were pretty much the same,” suggesting that capitalism like a viral condition produces many of the same recognizable feelings. More than that, one may not know of its transmission until one’s body symptomizes many of its compulsory affects and senses, or malaise and dysfunction, which the characters in the film perform with alacrity. One could say the genius of this meme-tastic lecture is its quick and exuberant re-articulation of that eminently quotable line in the film, “Wow! This is so metaphorical!” And we have not even begun to interrogate the mixed metaphors of parasitic relations produced by surplus value, theft, and the global circulation of Euro-American racism. What is clear is “we” are all living in a Parasite country, somewhere contained and somewhat Asian/American, whether in its dungeons, skid rows, mansions, or megastructures.

The space in and between “Asian” and “American” has always been a contentious one with multiple meanings delineated by a hyphen, a blank space, and a slash. If the hyphen connotes an otherness of the “forever foreigner,” the blank space emphasizes a citizenship claim that turns “Asian” into an adjective, which is a kind of corrective from a sense that the forever foreigner cannot be fully citizen or fully American. The slash turns the nationalist sentiment on its head by pointing to the transnational, diasporic and decolonial cultural meshings that makes disambiguation an impossible politic for understanding race, migration, and capitalism in the Asias, which includes Asian America. Asia/America is in this regard a geopolitical space that considers both the specificity of the countries where Asians reside and the inter-continental and inter-Asian predicaments that may in fact be countryless. Asia/America is both real and conceptual like the country called Capitalism.

Such a countryless country is lost on film critic Walter Chaw whose impassioned New York Times op-ed, “‘Parasite’ Won, but Asian-Americans Are Still Losing,” argues that Asian Americans have nothing to gain by Bong’s Oscar victory because the film has “nothing to do with people like me.” Chaw’s identity tantrum evokes the Chinese American cultural nationalism of the 1990s and subtends “Asian-Americans” to an unmarked cohesion and coherency dominated by East Asian, and more specifically Chinese American interests. It bears noting that Asian American transnational thinking has grappled with this misrepresentation, and advocated for studies of Asia/America beyond the racial hyphenation of Asian-America where Chaw is stuck. (Part of this has to do with the Times holding out on hyphenating Asian-American as a style issue in spite of the movement to drop the hyphen).

To put it another way, Chaw misapprehends Asian American solidarity as the occasion for consolidating Chinese American sensibilities fixed on a kind of macho binary thinking — a win/lose, liberal/conservative, us/them, male/female, East/West. Predictably, Donald Trump has also seized on the film’s “foreignness” and Oscar wins as incommensurable, which is consistent with his white nationalist mantras as well as the xenophobic tradition of “America First” that extends back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. What does the parasitic convergence of Trump nation and Chinese America portend? The question demands that we look back at the history of cultural nationalism and Cold War orientalism, which continue to be formidable force fields. Frank Chin, a Chinese American writer and proponent of cultural nationalism, would channel the heroic orthodoxy of Chinese origin stories as an antidote for the effete fictions that have castrated Chinese American manhood. Cold War orientalism is a postwar ideology that upholds American exceptionalism as a sentimental discourse that is forged through salvific (or “savior complex”) and satisfying bonds between Asians and Americans at home and abroad. Both issues are central to Asian American Studies as a field of study.

The middlebrow allure of getting Asian legibility and American satisfaction continues to drive many identity-driven narratives, confessionals and racial tropes that circulate widely in mainstream media. Chaw’s own origin story as one of the displaced “children of China’s 1949 revolution” saved ostensibly by capitalist America is a prime example of that necessary biography. It is the kind of “Asian” biography, perhaps the only kind, that would satisfy the requisite and repeating questions of the white gaze: “Where are you from?” and “Where are you really from?” Chaw’s Americanist alignment seeks to justify a form of straight Chinese American male privilege that is increasingly dissociated with the collective consciousness of Asian America as a transnational and decolonial project. Hence his imagined unity around the racial hyphenation of “Asian-Americans” against South Korean otherness is as jarring as his call for Chinese American director, Lulu Wang’s “The Farewell,” to be “our great hope for representation at the Oscars.”

Suffice to say, the violence of “our great hope” is ultimately about Chaw and his vexed Chineseness, and by extension, Chinese America’s conservative turn for proper and self-justifying representation, be it at the Oscars or at Harvard’s admission office. Is the unconscious sinicization of the great white hope the way to work through anti-Asian bias and assimilationist Chinese American angst that so many have experienced as teenagers growing up in the suburbs, including Chaw’s in Colorado? Being misrecognized for a relation of Bruce Lee as a child continues to haunt him, as do the racial taunts that countless Americans have to endure on a daily basis. But the problem of a deracinated and emasculated Chinese masculinity undergirding the American logic of multicultural inclusion is also a class critique, a problem of gender, a postcolonial issue, and a way to organize queer and cross-ethnic solidarities in a country called Capitalism. For the millions who have been rendered countryless by Capitalism and its corporate identitarian regimes, the critique of provincialism rings hollow when “Asian-America” is instrumentalized for a different kind of parochialism around race, gender, and class, one that is dangerously aligned with Trump’s America.

As the spread of the coronavirus unleashes new waves of racialized panic around “those Chinese people,” Asian Americans are similarly affected by its myriad viralities, epidemically and metaphorically. The fearmongering affecting Asians living in this country, like the offensive smell of the underclass depicted in the film, transcends the descriptive borders or identities that divide “us.” It returns us to the viral pedagogy of the meme, Bong axioms, and ever-proliferating cinematic stories that can revivify and redirect Asian American critique towards a more constellated approach of understanding global inequality. Now that is the kind of Asian/American “representation” I can get behind with or without any damn award.