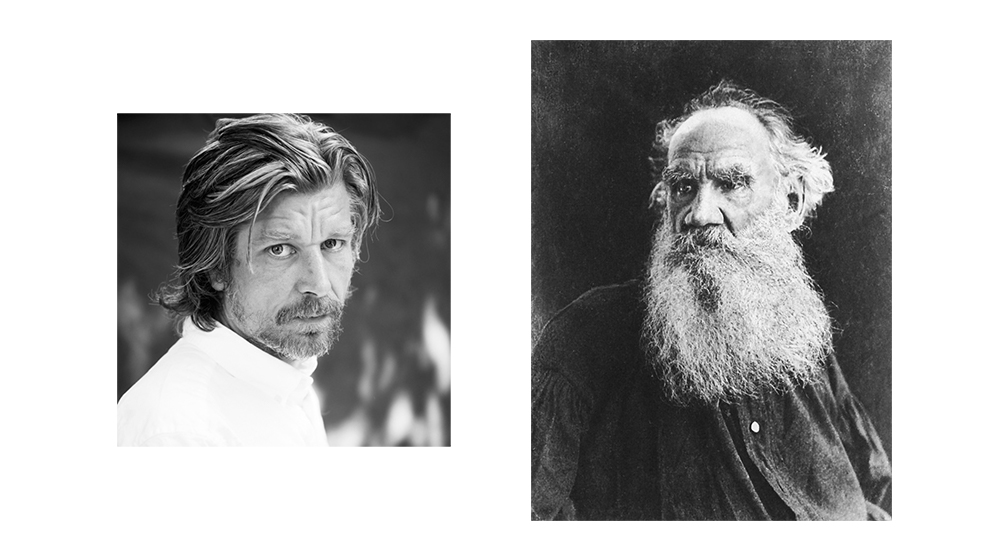

In Inadvertent, his good essay-lecture on the theme of “Why I Write” for the Yale library, Karl Ove Knausgaard remembers his boyhood reading habits: “I didn’t know anyone else who read except my brother, so I never talked about what I experienced in books, but it didn’t matter, the whole point of them being precisely that I read them alone, and yet I never felt like that, for while you were reading you were always together with someone else.” When I read Knausgaard, and I’ve read everything of his that’s been published in English except the last three-quarters of A Time for Everything (it felt like I didn’t have time to keep reading about angels), I do feel he’s the “someone else” whose presence I’m in.

I wrote him at his and his brother’s publishing house in Norway this spring to invite him for a conversation about Tolstoy, but I didn’t hear back from him. (It was a long shot.) Now I wish I could imagine into existence a talk with him about War and Peace. My number one novel is Anna Karenina, but War and Peace ain’t bad neither. For the last few months I’ve been reading it in Russian a page or two a night. Every so often, maybe because I have to read Russian very slowly, I stop in amazement and appreciation as I realize: That single paragraph there is ONE volume of Knausgaard! I love the depth of Knausgaard’s books, but reading War and Peace I keep stumbling upon molecules that seem to contain planets:

Near the altar of the church at Bald Hills there was a chapel over the tomb of the little princess, and in this chapel was a marble monument brought from Italy, representing an angel with outspread wings ready to fly upwards. The angel’s upper lip was slightly raised as though about to smile, and once on coming out of the chapel Prince Andrew and Princess Mary admitted to one another that the angel’s face reminded them strangely of the little princess. But what was still stranger, though of this Prince Andrew said nothing to his sister, was that in the expression the sculptor had happened to give the angel’s face, Prince Andrew read the same mild reproach he had read on the face of his dead wife: “Ah, why have you done this to me?”

As Tolstoy noted in one of his pedagogical essays, “Every artistic phrase … distinguishes itself from the inartistic in that it calls up countless possible thoughts, imaginings and revelations.” This moment in Prince Andrew’s life is one of those that vivifies thinking and feeling.

Knausgaard has these moments too, and whenever they happen, my sense of the world expands for a second into infinity. I didn’t complain to anybody about Volume 6 of My Struggle, except for the 400-page Hitler section, which, by reverse engineering could, I think, be condensed into one paragraph. Otherwise I’m completely down with My Struggle, the happiest extended literary experience I’ve had since I started reading Russian novels in the original.

But in Inadvertent, I was amused to learn that Knausgaard had only read War and Peace (“a book I love above all others”) twice. Twice! (“ … and both times I have been sucked into it, as happens only with the greatest of novels, when you invest more and deeper emotions into what you are reading than you do in your own life, and at times may find yourself yearning for the spaces opened up by the novel, even longing for its characters”). How many times should one read one’s book of books? Yes, War and Peace is a big book, but still!

My knowing of Knausgaard’s acknowledgment of War and Peace made me conscious of the resonance of passages where Tolstoy had condensed life into diamonds and that Knausgaard, in Struggle after Struggle, expanded into the stars. In his essay, Knausgaard points to this paragraph from Book VI, Chapter XIX (he or his translator Ingvild Burkey use Louise and Aylmer Maude’s translation):

After dinner Natasha, at Prince Andrew’s request, went to the clavichord and began singing. Prince Andrew stood by a window talking to the ladies and listened to her. In the midst of a phrase he ceased speaking and suddenly felt tears choking him, a thing he had thought impossible for him. He looked at Natasha as she sang, and something new and joyful stirred in his soul. He felt happy and at the same time sad. He had absolutely nothing to weep about yet he was ready to weep. What about? His former love? The little princess? His disillusionments? … His hopes for the future? … Yes and no. The chief reason was a sudden, vivid sense of the terrible contrast between something great and illimitable within him, and that limited and material that he, and even she, was. The contrast weighed on and yet cheered him while she sang.

One more scene from War and Peace that does for me in an instant what all of Knausgaard’s brilliant “Seasons” quartet did for me over days:

As often happens after long sleeplessness and long anxiety, he was seized by an unreasoning panic—it occurred to him that the child was dead. All that he saw and heard seemed to confirm this terror.

“All is over,” he thought, and a cold sweat broke out on his forehead. He went to the cot in confusion, sure that he would find it empty and that the nurse had been hiding the dead baby. He drew the curtain aside and for some time his frightened, restless eyes could not find the baby. At last he saw him: the rosy boy had tossed about till he lay across the bed with his head lower than the pillow, and was smacking his lips in his sleep and breathing evenly.

What I mean is that Tolstoy and Knausgaard are writers who get carried away and carry me away. They are exhaustive and intense, but like all great authors, they make me happy in their own ways.