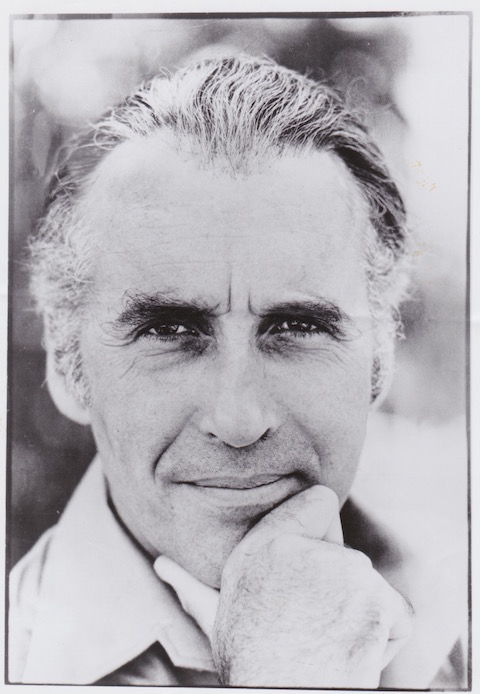

Our friend Ann Louise Bardach interviewed Christopher Lee for Los Angeles’s WET magazine in 1981. We post it with her permission here in memorium.

¤

Christopher Frank Carandini Lee was born in London on May 27, 1922. During WWII, he served in the British Royal Air Force in some intelligence capacity, the details of which he says he would rather not discuss. After the War, Lee decided to try acting. He appeared in his first film in 1949 and starred in The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957. Over the next decade, he became a fixture in the horror genre, often outclassing the gory potboilers in which he starred. In person, he’s quite tall but not spooky at all.

A.L. Bardach chats with Lee about his war years, which proved an odd sort of inspiration to his future career.

¤

A.L. BARDACH: Is Lee your real name?

CHRISTOPHER LEE: Yes. We are of Italian origin on my mother’s side. Lee is my father’s name. He was a professional soldier in the British army and his family came from the county of Hampshire, a Gypsy area of England. Lee is derived from the old English word “Leah,” meaning forest or wood, which is, of course, where Gypsies used to live. So I’m Gypsy on one side and Italian on the other.

Were you raised a Catholic?

Church of England. I was raised — like all boys of my background and upbringing — in a very traditional way indeed.

Presumably you attended English public school?

Yes. I took a scholarship at Eton and I took a scholarship at Wellington, which is an army school. I had a very conventional, traditional, what they call English upper-class upbringing. Not sheltered, luckily. I had to fend for myself at a fairly early age. Your comb is dropping out of your hair.

Thank you. What was the name of your first film?

It was called Corridor of Mirrors. It was made in Paris in 1947, directed by Terrence Young. I had one line.

When was your first prominent role?

I’m not too good at dates, but I would say in 1957 in Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. I played the wicked Marquis, who was later played by Basil Rathbone in the Ronald Coleman version. Then, of course, we had the Hammer period — between 1957 and ’70, more or less. I was never under contract, but I did a lot of movies for them.

Horror movies?

People call them horror movies. Some of them were, and some of them weren’t.

What was your favorite horror film?

Rasputin, because I was able to play a real person, not a fantasy.

Who directed Rasputin?

Don Sharp. In fact, I finished a movie with him not too long ago: Bear Island, shot in Alaska with Donald Sutherland and Vanessa Redgrave and Richard Widmark.

What part did you play?

A Polish scientist.

You were in, was it Dracula or Frankenstein?

Both. I played both and The Mummy, too. A long time ago.

That places you squarely in the sinister company of Bela Lugosi, Basil Rathbone, Vincent Price and friends.

A great friend of mine, Taft Schreiber, said something that I will never forget. He was a very charming, shrewd and delightful person, and he was the senior executive at MCA and Universal. He died in 1976 in a dreadful way: He was given the wrong blood after an operation. He said, “You know, there have been a great many British actors in the film world and many of them have left their mark playing villainous characters, people like Boris Karloff. Obviously. I had a natural bent for it, and I had the linguistic ability.

What languages do you speak? French and German?

Yes. And Italian. And a bit of Russian and Greek and Danish and Swedish.

Did you know an Englishman named Allan Beasley?

No. I am not permitted to discuss intelligence matters, and I don’t want to, because the past is the past. Some of it, all of it, is very vivid in my mind. Some of it comes back to me from day to day according to what is happening in the world. But one did not know people by their real names. You were a cipher — a code name or whatever.

I believe Allan Beasley worked for the English CIA. He was also a linguist and wrote travel books.

Oh, that could be the M15, which is military intelligence, or the M16, which is civilian intelligence, or SIS, the Special Intelligence Service.

He was a friend of Kenneth Tynan’s and, according to Tynan, he committed suicide when his cover was blown.

Oh, well, how do you know he committed suicide?

I see. That’s a good question.

“How do you know?” is a good question. That’s why I’ve said that these boys don’t play at games. We had nothing to do with the major war criminals, though. We were afteranybody, anybody who was on a list we were given.

How many people were on the list?

The figures were enormous. There were literally thousands of people arrested. I think out of that number, only some-thing like 150 were executed, actually.

Executed where? At Nuremberg?

I had nothing to do with that. The Nuremberg executions were carried out by an American hangman, a master sergeant named John Woods of San Antonio, Texas. We operated wherever we were told to go.

Were you present at any executions?

Yes, quite a few.

Twenty?

More than that.

Fifty?

More than that.

Hundred?

Not quite.

Did you ever see a war criminal show signs of remorse?

No, none whatsoever. They believed unshakeably, with total conviction and total sincerity, that they were doing the right thing. I’ll never forget that. It explains a great deal.

How old were you?

I was young. Twenty-four. Having been through the war, I was fairly inured to the bestiality or the cliche of man’s inhumanity to man. But it wasn’t until I saw those camps that I had any idea .. .

Which camps did you visit?

I really don’t want to discuss that. Not all of them, of course. Sometimes two days later, sometimes two, three weeks after, months. But when we saw the people responsible, we saw what they had done and spoke to them and interrogated them. You must remember that there were hundreds of people involved. It was difficult to feel that they were human beings because you had seen what they had done. I don’t recollect any remote indication of remorse right up until the moment of execution.

That must have been some experience for a twenty-fouryear-old English boy.

I wasn’t a boy and I wasn’t all that English.

Do you think your ability to characterize evil so well comes from your Nazi hunting and surveillance?

Oh no.

But in 1946, you were investigating the world’s evilest men and in 1947, you began to play them in the theater and films. Did you ever use the specific characteristics of a war criminal in a part you’ve played in a film?

Oh, yes. The clinical indifference, the emotionlessness, the cold, callous attitude.

Can you think of specific parts corresponding to specific people?

Yes, there have been instances, and I’ll tell you exactly what they are: Rochefort in The Three Musketeers, the great swordsman of France who had a sardonic sense of humor although he was a very evil guy; and Scalamandre, the professional assassin in The Man With the Golden Gun.

How about Rasputin?

Now that’s a different thing. Rasputin I based upon what knowledge I had about him. Of course he was a very complex individual. I met his daughter, Maria, around two years ago, before she died. She told me that I was like her father. She had seen the film. A compliment, I suppose.

Were you bothered by playing all the bad guys, monsters, and villains?

Oh no. They are much more fun to play — much more interesting than anybody else. They are usually better written, with more dimension to the characters. They’re wittier. People remember them better.

In the War, were you in a situation where you had to kill people?

Oh, I don’t want to get into that really. A man who drops bombs kills people. I’d rather not discuss that, I don’t really want to give the impression that I was some sort of mass murderer because I was in a plane that dropped bombs. I was one of 10,000s of people…I was, if you like to call it, involved in the infliction of death; so were millions of people. I was taught to do a lot of unattractive things, let’s put it that way. You can call the murder “licensed murder” or “political murder”— it doesn’t excuse it—but it’s war.