En route to my coffee date with Jawdat Michael Zuhair, a Palestinian peace activist from Gaza, I wondered what it would be like to finally meet him in person. Jawdat had suggested that we brunch at Café Hillel on Jaffa Street because it was close to the bus stop he knew at Damascus Gate. I paused at the thought that a different branch of Café Hillel, in Jerusalem’s Germany Colony, just one mile from my home, had been the site of a suicide bombing attack by a Palestinian that killed seven and injured more than 50 in September 2003.

Jawdat and I had first met virtually in May 2018 when I was given the opportunity to host eight Gazan peace activists in my living room — via Skype. They were members of a group in Gaza City that promotes peace and education for democracy in Gaza. The “Youth Committee” is led by a friend of mine, Rami Aman. Rami had initiated a project called “From Gaza to America: Let’s Share Ramadan Together,” supported financially by the US Consulate, in which members of the Youth Committee in Gaza skype with folks in other countries over the iftar (break-the-fast) meal.

Rami created the project to connect Gazans to the outside world. Though I have been involved in Israeli-Palestinian peace activism for more than 20 years, Rami was the only Gazan I knew before participating in his project; we had met via Skype in 2014, at an event sponsored by the US Consulate in Jerusalem. In Israel, Gazans have been so “otherized,” leading to a distance not only physical but to a greater extent — psychological/emotional. I have many Palestinian friends and have always been interested in meeting people from Gaza, so my family and I had welcomed the opportunity to meet some of Rami’s partners, including Jawdat, Fatma, Ramiz, Mohammed, Mahmoud, and the smiley Alaa, 13, sporting her fashionably ripped jeans. My three school-age sons bobbed their heads around my laptop, intrigued to grab some face time with Gazans, who are almost never seen in Israel, even in the media.

As it turned out, on that balmy Saturday night, my husband and I chatted primarily with Jawdat. A 27-year-old program manager for a church training center, Jawdat is one of Gaza’s 1000-strong Christian community, a tiny minority among nearly two million predominantly Muslim residents. As Jawdat related how he wove the Committee’s peace efforts into his daily life, threading peace activities into his work schedule at the church and around visits to the YMCA, my husband I were both struck by his passion and commitment.

The experience was uplifting and inspiring. Buoyed by the discovery that Israeli peace activists had several real partners in Gaza, I wrote the story up for Tablet and shared it on Facebook. I headed out to the neighborhood pool with my kids to savor the gathering sunshine.

That assumption of alliance shattered into pieces several hours later when a startling image suddenly appeared on my personal Facebook page, posted by a reader I did not know.

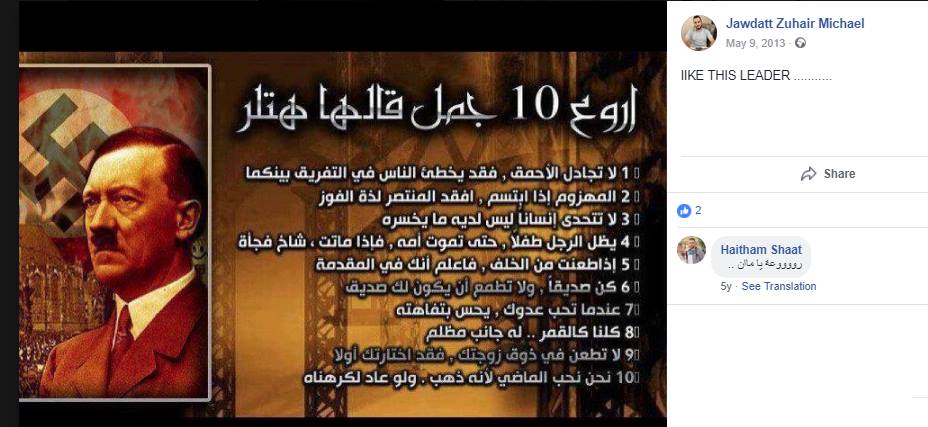

“Look who your new friend loves,” noted the reader sardonically. He had shared an imposing screenshot from Jawdat’s Facebook page of a uniformed Hitler standing against the backdrop of a red flag with a swastika, and to the right, a list of Hitler’s sayings translated into Arabic against ironworks faded into copper haze.

If that were not enough, the image was accompanied by Jawdat’s words: LIKE THIS LEADER.

I felt my breath quicken and sweat bead on my neck. Then my eyes caught the date: May 9, 2013. Ah, the post was five years old. Okay, at least that. But it was still hard to swallow. “Neo-Nazi” didn’t seem to jive with the impression I’d gotten of Jawdat while skyping several weeks prior. Jawdat came across as gentle and likable; he talked about supervising the first mobile mammogram unit in Gaza. He also shared his experiences volunteering at the YMCA, encouraging children who were suffering from the conflict to paint their fears.

Of course, I knew that being gentle did not preclude one from being a Nazi sympathizer. I could already hear the resolute voices of friends and acquaintances who doubted any Palestinian impulses for peace.

Ruth, how many Nazi leaders were kind, likable, educated people who were good to their own families? To their pets? You are so naïve. Why would anyone suffering like Gazans perceive you and other Israelis to be anything other than their hostile enemies? And did you really think you could get a sense of a person on a screen?

Still, I felt I had gleaned something in our hour-long Skype visit. Nothing about Jawdat bespoke support for violence, fascism, or antisemitism. More importantly, he didn’t seem like the type to conceal things. Yet I could not ignore the fact that our conversation had been virtual. While I had spoken several times to Rami, the Youth Committee’s founder, over the years and even met him in person in the US in 2017, I had never met Jawdat in real life.

I sucked in my breath. Jawdat was a friend on Facebook. I waited to see if he would respond to the stranger’s query.

“Since 2013, you are talking about five years of knowledge, relationships, and political awareness, bro,” commented Jawdat later that day.

To understand the post better, I scheduled a follow-up conversation with Jawdat. It took several weeks to coordinate due to the rolling blackouts of electricity that are commonplace in Gaza. As of this writing, Gazans have electricity for 8 hours per day — sometimes inconsistently, and sometimes with unexpected additional stretches — due to an electricity crisis resulting from conflict between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, and financial issues with Israel. Just last summer, the allocation was limited to four hours a day.

Ten minutes into our Skype conversation, Jawdat disclosed the real reason for the Hitler post — it turned out to be less dramatic and sinister than I had expected, even anticlimactic. “I’m ashamed to admit it,” confessed Jawdat, sheepishly, “but it was a case of pure ignorance.”

On the screen, I watched him shrug his shoulders. “To tell you the truth, I really didn’t even know who Hitler was. I only knew that the Israelis hated him, and that was enough of a reason at the time for me to ‘like’ him. But I had no idea what he had done, the genocide he had masterminded, why Israelis hated him so much.” Jawdat’s brown eyes met my gaze. His expression communicated sincerity. Nevertheless, his confession surprised me. On the roster of reasons I had considered for why Jawdat had posted Hitler, ignorance was certainly not one of them.

But what about my own ignorance? Did I know the basic fears besetting Palestinians in Gaza, or even those who lived much closer to me in my hometown of Jerusalem? How familiar was I with the realities of the almost two million residents of Gaza? I was not aiming for false equivalence; nevertheless, his ignorance drew my attention to my own.

Jawdat proceeded to translate Hitler’s quotes, which appeared in the photo under a heading of “10 best quips that Hitler said”. It turned out these particular sayings had nothing to do with anti-Semitism or National Socialist ideology. They included things like this: “If you stab someone from behind, know that you are now in front.” And “Don’t challenge someone who has nothing to lose.” “A man remains a child until his mother dies, and when she dies, he quickly becomes old.” With a critical eye, one might interpret these sayings as general suggestions for aspiring fascists, aggressive in tone. But there was nary a word about murdering Jews.

In the middle, Jawdat took a deep breath. “I don’t even know if I believe that Hitler ever said any of these things,” he announced, trying to distance himself from the quotes, and from the Jawdat who posted them. What this Gazan didn’t say was that Jews were regularly called Nazis in the Palestinian media, that it was part of a mainstream discourse. We are seen as fascists and imperialists, explained a friend of mine who is fluent in Arabic and follows Palestinian media. The Jawdat of then probably didn’t think twice about sharing the post. But the Jawdat of today no longer saw it as legitimate.

Then, somehow, magically, after broaching this sensitive matter, Jawdat and I fell into an open and intimate conversation about what he thought of Jewish Israelis. Gone was the talk about Nationalist Socialism, peace partnerships and the Youth Committee. Instead, we engaged in a frank meditation on identity.

In that 90-minute chat, Jawdat shared that since 2013, he had indeed undergone a transformation. But it did not reflect a conversion from raging anti-Semite to peace activist. It was the evolution from a person who did not believe in his power to affect change into an individual who believed that he could. Through Jawdat’s peace work with the Youth Committee, he had grown a sense of agency.

“Mind you, I never supported hurting Jews,” said Jawdat. “They are familiar to me from the Old Testament and from previous visits to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. I’ve met many nice Jewish Israelis. I myself am a religious minority in Gaza. It’s a Christian principle to not retaliate, so we are against violence altogether.”

Then he paused.

“Back then, I didn’t think like a peacemaker,” said Jawdat. “I focused on my studies, my friends. Though I supported peace with Israel as some faraway concept, in my mind Israel represented this one big bad thing.”

With no familiarity with or experience in peace, Jawdat had no experience of seeing other, reaching out to other, inquiring about other, knowing other. But after he started working with the Youth Committee in 2016, pursuing peace and democracy had become a life passion. “Joining our team, I felt the power and hope in our vision.” That translated into opening his eyes to understand, and embrace, other. The pursuit of peace went from something that lived outside Jawdat to something that had burrowed inside.

Listening to Jawdat, I realized that a similar process had happened to me. The pursuit of peace had also found itself inside me. I too had evolved into someone with a great passion to change my society from within.

“Christians, Muslims, and Jews — we are partners on this land,” affirmed Jawdat.

¤

In late December, Jawdat got a nearly-impossible-to-obtain permit to visit Israel for the Christmas holiday. Which is how I found myself suddenly sitting across the table from him, cupping a mug of steaming herbal tea, a slice of hot chocolate cake between us.

For me, the route to the cafe was a 10-minute drive and a short, wet walk from the car. Jawdatt came in from Jericho, which is 15 miles northeast of Jerusalem but a laborious hour-long trip comprising three buses and a checkpoint. His black leather jacket was soaked and his jeans dripped, water pooling on the café floor. But his eyes were alive and luminous.

The conversation flowed. Jawdat spoke about future activities with the Bob Marley Group in Tel Aviv, after-school programs with kids, a desire to learn how to pen articles, how we could marry our resources to work together.

“We sprinkle seeds of hope, and hope to enjoy the fruits, even if it takes 50 years.” Then he giggled, as if disclosing a secret. “You know, we start off our day in the office saying ‘Shalom’ to each other.”

The rain fell harder, smacking the ground. Gusts of winds picked up fiercely, and it almost looked like it was raining sideways. But Jawdat didn’t seem to notice. Motioning with his hands, he was waxing on about pursuing different peacemaking activities and educational programs, underscoring the challenge of keeping things sustainable in an area of lawlessness.

As compared to seeing Jawdat on my computer screen, Jawdat in real life was lovelier. Even softer. Yet more earnest. A spirited person with unending optimism. His face marked by a beard often broke into a smile. He had a cute little signature laugh, with crinkly eyes. Skype hadn’t allowed me to fully appreciate Jawdat’s gift of congeniality. Our morning together flew by.

As we embraced under the awning on the wet ground, I thought about how uncommon our meeting was. The unfortunate fallout of our peoples not knowing each other.

And so this story is different than the one I thought I’d write. It’s certainly not about a Nazi sympathizer masquerading as a peace activist. It’s about the ignorance between us, Israelis and Gazans, about the distrust that a reader feels that Gazans could be genuine peace activists. The very idea of someone being good seemed to elicit an automatic response of finding evidence to the contrary. And that evidence turned out to be untrue. Don’t we all somehow fall prey to our disbelief? And how likely are we to continue to fear and fight each other if we don’t know each other, if we remain strangers and uninformed?

What do Gazans need to learn about Israelis’ passions and fears, and what do we need to learn about theirs? How can we move from seeing the nearly two million residents of Gaza as people, not solely as the pawns of Hamas? How can they move to seeing us something other than occupiers and soldiers at the border who want to grab their land and kill them?

I don’t have the answers to these questions. But I can tell you this: I met a man from Gaza and took the time to get to know him — and he took the time to get to know me.