As the Trump Administration focuses on expansion of border patrol agents by lowering recruitment and admission standards, we would be wise to look back at another time in history in which these agents played a controversial role: the very time in which their standards were put in place.

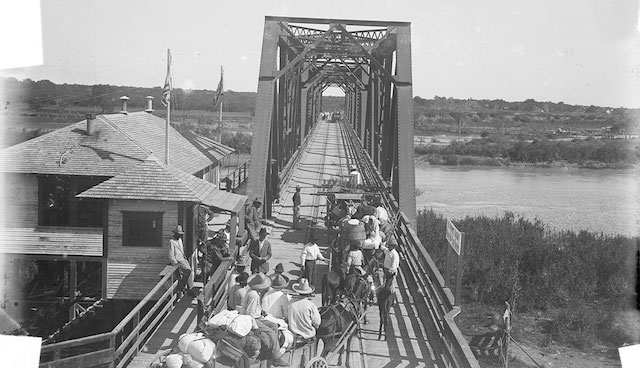

In early 2016 the Bullock Texas State History Museum opened the exhibit “Life and Death on the Border, 1910 – 1920” to memorialized a period of anti-Mexican violence that resulted in hundreds if not thousands of killings. It was the first state project that accounted for the role of state politicians, administrators, and police in creating a period of racial terror.

As a professor of American and Ethnic Studies at Brown University, alongside an entire group of professors, I collaborated with the staff, and with local residents to curate the exhibit.

Over 250 filled the lecture hall for the opening symposium and over the course of 10 weeks, approximately 40,000 people visited.

The award-winning exhibit displayed objects preserved in the private archives that were crucial to supplement the exhibit because state institutions had neglected to preserve accounts of the injustices that occurred 100 years ago. Family portraits and documents shared space in the exhibit with three bound volumes of Texas ranger abuses.

Looking back at the series of events that swiftly led to such violence, one can’t help but see parallels starting to emerge.

In January 1919, a committee of state legislators met to consider Texas’s role in anti-Mexican violence. The investigation was prompted by State Representative José T. Canales’s proposal to reform the Texas state police force by reducing its size, increasing agent salaries, and placing agents under bond. Whereas in 1915, 26 agents policed the state, at the request of politicians, the force had grown to approximately 1,350 agents by 1919.

However, the rapid growth of the force fueled abuses by state agents.

The 1919 investigation showed state agents regularly used extralegal violence and often colluded with local civilians in acts of vigilantism to incite racial terror in the border region. The committee did not call for the prosecution of any of the agents, but did agree that the number of the police force should be reduced.

This investigation is a reminder of the dangerous consequences when federal and state agents, authorized with guns and the law, are not properly trained or vetted. The establishment of the Border Patrol agency in 1924 aimed, in part, to develop a professional force of border agents. In the early years these agents turned their eye from policing unsanctioned European and Asian immigration and made Mexicans the face of unwanted immigration.

Today, the current administration is calling for the expansion of the agency by adding 15,000 new Border Patrol and ICE officers. To do this, a drafted report suggests waiving a required polygraph test (required by the Anti-Border Corruption Act of 2010) and removing language proficiency tests from Border Patrol entry exams.

This rapid effort to expand is in the midst of reports of border agent abuse and misconduct. In 2013 the Office of Inspector General examined CBP training to address excessive use of force incidents. The report outlined that polygraph testing 100 percent of prospective law enforcement agents “eliminates applicants who should not be in law enforcement.”

Having grown up in south Texas and knowing border patrol agents and local law enforcement, I know the work battling cartels is dangerous and taxing. This work must be conducted by the most intelligent, skilled, and compassionate agents.

Jeff Sessions’s speech in April in Nogales distorted the reality of the border by characterizing all immigrants and refugees as gang members and drug smugglers wielding machetes. He erased the great humanitarian needs on the border.

Americans should heed the warnings of immigrant rights and human rights organizations, and the border agents themselves, that warn of abuse at the hands of undertrained and poorly vetted agents. In 2014 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees released a report in response to the humanitarian needs of unaccompanied minors seeking asylum in the United States. It recommended more training, not less, for officers “on the basic norms and principles of international human rights and refugee law, including the fundamental principles of nondiscriminatory treatment, best interests of the child, non-refoulement, family unity, due process of the law, and non-detention or other restriction of liberty.” We should follow the suggestions for humanitarian solutions, not those inspired by anti-immigrant ideologues.

A sculpture added to the Bullock exhibit depicts a man carrying his wife and child on his shoulders. The artist Luis Jiménez described creating the piece in response to the misrepresentation of immigrants and hoped to humanize those who face exploitation and death in crossing into the United States. This subtle, but powerful, curatorial choice is a reminder that struggles for life and dignity in the borderlands continues.