Some time ago, UPS delivered a box to me from… let us say the past. On browning cardboard, in fading Sharpie letters, I recognized my own handwriting, circa Kurt Cobain’s demise: COLLEGE NOTES. I rifled through the box in search of one binder only — the one containing my notes from Gilberto Perez’s Film Studies lecture class, which I took the semester I graduated from Sarah Lawrence College. Ever since Perez’s unexpected death in 2015, at age 71, I had wanted to reconstruct, as closely as possible, the lilt of his Cuban-American voice in that small lecture-and-screening room, where he initiated me and perhaps 50 other students to his love for films by Michelangelo Antonioni, Buster Keaton, Agnès Varda, Luis Buñuel, John Ford and — I wanted the syllabus to recall exactly which films Perez screened for us. Even though the lectures took place in the afternoon, Gil — Sarah Lawrence relishes its first-name informality — set the screening times for six o’clock or so, because, he said, he wanted our experience to approximate that of actual moviegoing.

In one sense, I didn’t really need those missing notes, because Gil’s book, The Material Ghost: Films and Their Medium, now a classic in Film Studies, contains his lectures’ intellectual ballast as well hints of his willingness to poke laconically — and, in person, with slight smile and raised eyebrow — at academic shibboleths: “No one understands Lacan very well”; “Does Hitchcock deserve his reputation?” The opening autobiographical section that recalls Gil’s movie-going adolescence in 1950s Havana, before he to came America “in the early sixties,” is worth the price of admission. Both Richard Brody, and, in our own pages, Lanie Presswood, illuminate Gil’s complex interweaving of film studies and rhetoric in the posthumously published volume, The Eloquent Screen: A Rhetoric of Film (2019). However, I haven’t actually “read” either of Gil’s books in the usual sense. Instead, I’ve scrabbled backward from their indices, looking for clues to what seemed, during his lectures, like passing comments on particular moments in films — asides that seemed, even then, to lead deep into the films’ very mysteries.

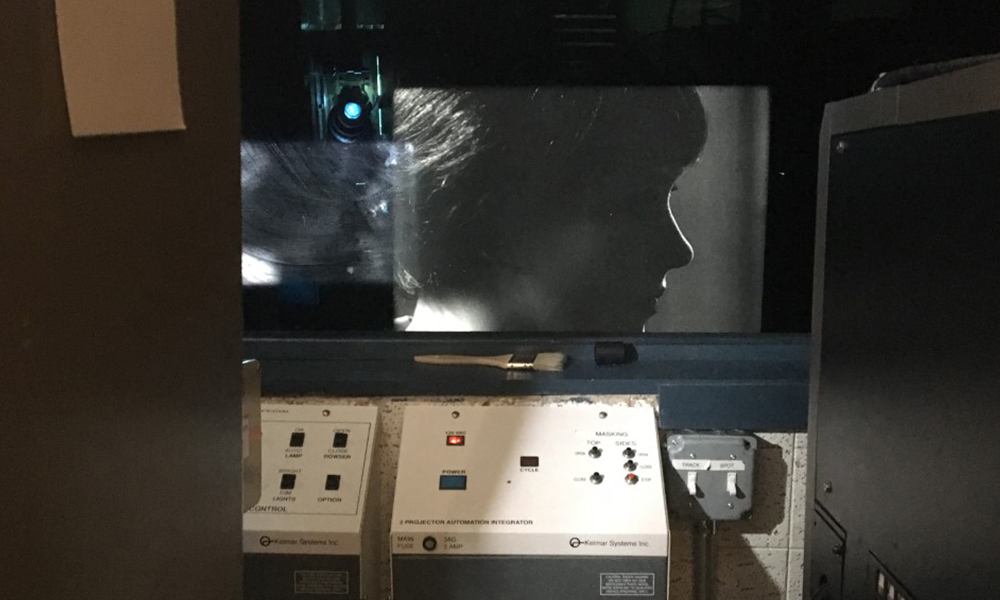

Gil’s dialectical turn of mind — pointed out movingly by his wife, Diane Stevenson, in her note to The Eloquent Screen — pervades all his thinking and may have given his ideas, at least to my less-trained mind, that just-out-of-reach quality when I was 20. “[T]he camera is not the only machine that makes the film image,” he emphasizes at the outset of The Material Ghost. “The projector, the magic lantern, animates the track of light with its own light, brings the imprint of life to new life on the screen.” I thought of Gil’s formulation when I saw this photo, taken from Film Forum’s projection booth, of Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962), a film I first saw in his class. The image of Karina, her face in profile against the window, while her character, the prostitute Nana, is interrogated by a policeman, seems to emanate from the screen itself; but at the same time, because the projection booth’s light casts a bright square on the glass that separates the booth from theatre itself, we are aware of another, co-equal, source of “new life.” I’m sure Gil’s near-rhyme of “light” and “life” isn’t coincidental.

Gil, who considered film an “art that peaked in the sixties and has not been matched since,” emphasized how his beloved French New Wave directors — many of whose films, it later occurred to me, he probably saw in theaters as they were released — broke with convention by relying exclusively on natural light. He pointed out how, in this very scene, the sunlight coming through the window behind Karina’s face leaves it under-exposed, whereas previous directors — such as, I wanted to ask him years later, Otto Preminger in Laura (1944), when Dana Andrews, playing a detective, shines an interrogation light directly in the face of Gene Tierney’s character? — would have lit her more conventionally.

In his lectures on Jean Renior’s Toni (1935), Gil emphasized not light, but sound. At the time I didn’t realize what an idiosyncratic choice it was for him to screen the proto-neorealist Toni, shot on location in the South of France, with a cast of many non-professionals, including Charles Blavette in the title role, instead The Rules of the Game or any of Renior’s other canonical films. When Gil replayed the film’s dramatic ending, he drew our attention to the sound of Blavette’s feet pounding on the metal bridge that leads to the station in Les Martigues. The moment carries high drama because Toni — who, like the many immigrants in the film’s narrative, entered the town by train on the same bridge — flees the police, who believe he has committed a murder. When I first picked up The Eloquent Screen, I flipped straight to the index to see if Gil had written about that moment, and indeed he refers to “the sound of [Toni’s] hurried footsteps on the bridge, an eloquent human detail resounding against the big alien machinery about to crush him.” Gil’s point isn’t about film technology per se — Renior used sync sound on Toni — but about the use of that technology to humanize a character. Very shortly, the sound of Blavette’s human footfalls, recorded by another human with a hand-held microphone, end when his character reaches the other side of the bridge and a townsperson, overeager to help the police, shoots him to death.

Gil’s knowledge of the films he loved was so comprehensive that, at times, he seemed to speaking to us from within the filmic world itself. In the transgressive ending of Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961), the camera cuts from a flaming crown of thorns’ circular shape to the revolving circle of a rockabilly 45 vinyl, “Shimmy Doll,” whose staccato guitar part accompanies a card game — or a threesome in the making? — between a former nun-to-be, her male cousin, and their female servant. If Gil had seen Viridiana upon its release, he’d have been eighteen or so, just about his future students’ ages, and records like “Shimmy Doll” would still have been in jukeboxes — though not in Spain, where Buñuel, Gil related to us, made his film in the teeth of Franco’s censors. Actually, I didn’t notice the implied equivalence between the crown of thorns and the record until I’d seen Viridiana, oh, seven or eight times over about the next twenty years. However, I was initially drawn back to the film in order to relive that moment when Gil stood before the movie screen with his Cheshire Cat smile and recited for us, from memory, the rockin’ lyrics that close out the film: “Is she fat or is she thin? / I wish I knew what shape she’s in / Shake, shimmy doll, shake / Shake your cares away….”

Top image courtesy of Carolyn Funk.