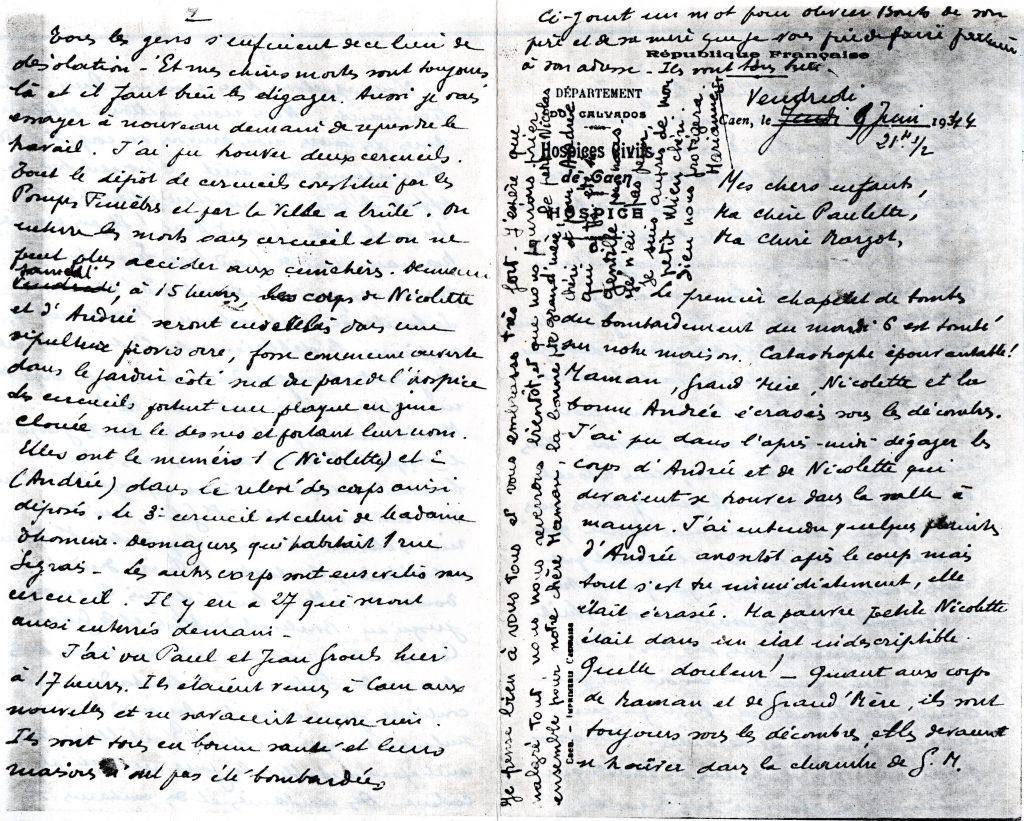

The first bombs on Tuesday the 6th fell on our house. A dreadful catastrophe! Mother, grandmother, Nicolette, and Andrée crushed beneath the rubble.

So begins my grandfather’s letter, dated June 9, 1944, three days after the D-Day landing in Normandy. Passed from one person to the next in the chaos of the war, the letter reached my mother in Paris two weeks later. Her own letter of June 7, addressed to a house that no longer existed, took even longer to reach my grandfather, who had taken refuge in an abbey.

The day my great-grandmother, grandmother, and aunt were killed by Allied bombs, more than 4,000 Allied soldiers died; by the time the Battle of Normandy was over, three months later, an estimated 54,000 Allied soldiers had lost their lives.

As a dual citizen of France and the United States, I sometimes feel embarrassed mentioning my family’s losses. The estimated number of French civilians killed on D-Day — 2,500 — is roughly equivalent to the number of American deaths that day; 20,000 civilians are estimated to have been killed over the course of the battle. Still, it can seem impolite to mention those deaths when the Allies were there to rid France of the Germans, and the military’s own losses were so devastating.

And yet, from my grandfather’s letter: The house is gone. Nothing but an immense field of rubble … We called. We listened. Nothing. Terrifying silence … Hours later, we found Andrée’s body … After great effort, my dear little Nicolette’s body. In such a state! Good God! And still nothing of Mother, nothing of Grandmother … the bombing continues.

The phrase “civilian casualties” is almost always preceded by the words “to say nothing of” (“4,496 troops died in Iraq, to say nothing of civilian casualties”), and for the most part, we do say nothing. Dead civilians are “collateral damage” — literally, secondary damage. We do shamefully little for our veterans, though we’re grateful for their service; any mention of civilian deaths seems impolite precisely because it seems like an absence of gratitude.

Most Germans had actually left Caen by June 6, a fact the Allies knew, prompting one British historian to call the bombing of Caen “close to a war crime;” there are also indications that some planes flew too high to hit their targets accurately. But my mother’s family was deeply grateful for the Allies. Living in Caen, they had suffered for four years under a regime of daily humiliations and threats, of near-starvation rations. None of the survivors I knew referred to the deaths of their loved ones as a crime. Caen was bombed in order to isolate the Germans by destroying lines of communication. To call that a war crime is to fall into the same black-and-white thinking that leads us to avoid mentioning civilian deaths in the first place.

Some war acts are clearly evil, some clearly heroic, but the picture offered by most reports is of a confusing and terrifying mixture, a world of sorrow. Surely, grateful respect for a soldier’s courage and sacrifice depends on being honest about that world. I live in a rural county, where many of our teenagers join the military; before he deployed, one boy told me he hoped he wouldn’t have to kill anyone. Lying to soldiers about what we’re sending them to do, trying to sanitize the whole business of war — how can that be a sign of respect or gratitude?

As Aeschylus observed, “the first casualty in war is truth,” but deception is not just a consequence of war, it’s a primary cause. There are flagrant lies — false claims about a perceived enemy, for example — but equally dangerous are the lies of omission upon which our appetite for war depends.

This year, as we celebrate the 75th anniversary of D-Day and remember our fallen soldiers, let us also remember the thousands upon thousands of ordinary people who died beneath the rubble.