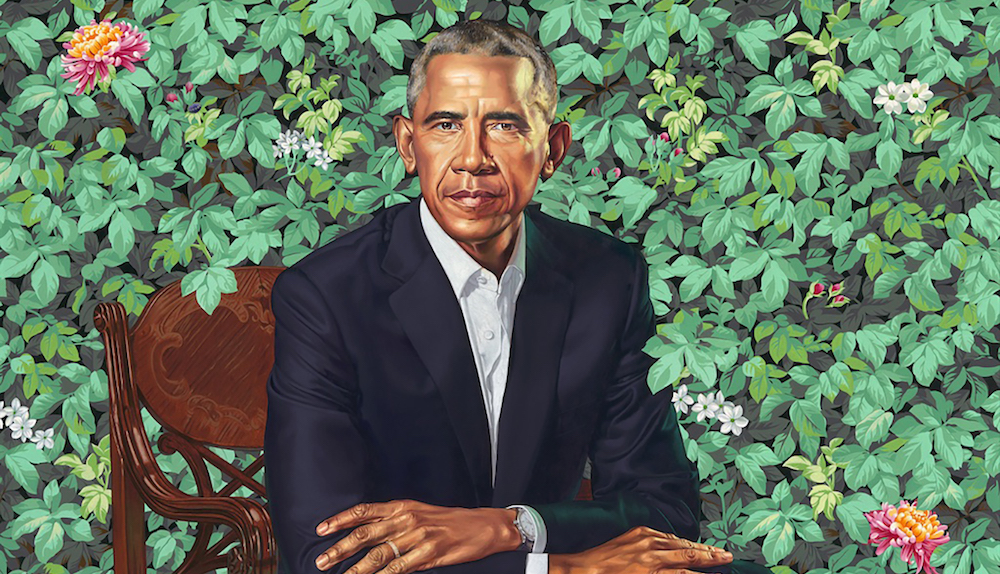

Earlier this year, the official portraits of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama were unveiled. These portraits were particularly momentous because they were of our country’s first Black president and first lady. But also of importance was that both the president and first lady chose Black artists — Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald — to paint their portraits.

Upon the unveiling, President Obama reflected on the significance of his choice of artist on Instagram saying, “Today, @KehindeWiley and @ASherald became the first black artists to create official presidential portraits for the Smithsonian […] Thanks to Kehinde and Amy, generations of Americans — and young people from all around the world — will visit the National Portrait Gallery and see this country through a new lens.” First Lady Michelle Obama echoed similar sentiments in her own Instagram post.

For his part, the magnitude of his dual role as the portrait artist for the first Black president and as the first Black presidential portrait artist was not lost on Wiley. “We can’t not recognize the important significance of representation in art and the decision that this president and first lady have made in choosing artists like ourselves,” Wiley told CNN. “[T]hey’re signaling to the rest of the world that it is OK to occupy skin that happens to look like this […] on the great walls of museums in the world.”

This artistic choice made by President and First Lady Obama about who would see them and who would translate their vision into an artistic portrait also bears consideration in the realm of literature and most particularly in biography, where the lens of the biographer can be compared to the lens of the portrait artist. Meanwhile, in the broader literary world, across nonfiction and fiction genres, questions of authority, authenticity, and appropriation keep bubbling up. The key question debated time and again is: “Who is permitted to tell whose story?” And at the root of this question lies the deeper question: “Should non-marginalized writers write about marginalized people?”

These central questions are batted back and forth in literary panels and articles, as writers with marginalized identities claim that non-marginalized writers, usually white and heterosexual, have no right to write about their communities, and that their work is inauthentic and culturally appropriative. Meanwhile, the non-marginalized view their work as imaginative, not transgressive, and justify it by voicing concerns about censorship and artistic constraints, declaring that nobody should be able to dictate to anyone else who and what they can create art about.

In 2016, the New York Times explored “Who Gets To Tell Other People’s Stories” in its series, Two Writers on this Topic. Anna Holmes took the position that writers should have the freedom to write beyond their scope of experience, but noted that it is important that they are driven by a motive of “empathy” rather than of “exploitation” in telling other people’s stories. “I am not of the opinion that […] artists cannot, or should not, attempt to tell the stories of people unlike themselves — and I am resistant to claims that, for instance, men are by definition unable to paint honest portrayals of women. (Or Koreans of Latinos, or African-Americans of, say, the white Amish.)” Pointing to a related essay by George Packer, Holmes suggested that there is “a robust, if uneasy, coexistence between the idea that identity is part of experience, and that experience (or the absence of such) should not preclude anyone from telling other people’s stories.”

Holmes’s counterpart in the column, writer, James Packer, essentially agreed with Holmes but spoke less of the identity of the writer or their subject, instead focusing on what it takes for the writer to reach a deep understanding of the humanity of their subject. “If you don’t open your heart to somebody, feel the weight of his individuality, expose yourself to his predicament, how can you possibly hope to understand him?”

A few months later, in an opinion piece also in the New York Times entitled “Who Gets To Write What,” Kaitlyn Greenidge, a Black writer, defended the right of writers to write about things outside their experience, “A writer has the right to inhabit any character she pleases — she’s always had it and will continue to have it.” But Greenridge tempered this with the caveat that writers shouldn’t presume that they are exempt from criticism if their portrayals are inaccurate or lack depth or nuance. “The complaint seems to be less that some people ask writers to think about cultural appropriation, and more that a writer wishes her work not to be critiqued for doing so, that instead she get a gold star for trying.”

Moreover, Greenidge addresses the “paranoia about nonexistent censorship” amongst writers seeking to write what they want while also remaining above reproach, by pointing to this quote from lauded Black writer Toni Morrison: “What I think the political correctness debate is really about is the power to be able to define. The definers want the power to name. And the defined are now taking that power away from them.”

This conversation about authenticity, authority, and appropriation is especially crucial and relevant to the genre of biography, which can be regarded as the literary cousin to portraiture, a genre specifically tasked with telling other people’s real-life stories. For the past five years I’ve been working on a biography about Lakshmi Shankar, a Grammy-nominated Hindustani singer who played a key role in the movement that brought Indian music to the West in the late 1960s. Last year, I participated on a panel at the 2017 Biographers International Organization (BIO) conference entitled, “Whose Lives Matter, and Who Should Be Writing Them.” On this panel, which was mostly made up of writers of color writing about people of color, we talked about the challenges of writing about subjects who’ve been marginalized by history in various ways.

In terms of considering the panel’s first question — “Whose lives matter?” — in a 2016 piece I wrote for Los Angeles Review of Books entitled “Biography: Where White Lives Matter,” I observed that the field of biography is overwhelmingly biased towards publishing and promoting biographies about white subjects, which results in a reinforcement of cultural erasure. I went on to attribute this in part to the fact that like the biographies that are most often published, the realm of biography — from publishers, to editors, to agents, to organizations — is overwhelmingly white. Therefore, through their composition, structure, and actions, irrespective of their rhetoric, the publishing sector articulates whose life stories they believe matter. In the piece, I predicted that the end of Obama’s presidency would usher in several biographies, and I pondered about how his racial identity would be treated by presidential biographers, who are overwhelmingly white. If the racial identity of President Obama’s portrait artist holds significance, isn’t the racial identity of his biographer relevant to how his story might be told?

The second question our panel considered — “Who should be writing them?” — is a fraught, complicated question, and my thoughts on it are necessarily layered. Essentially, my perspective can be summed up in four parts:

First, I believe, in theory, most anyone can write about most anyone else.

Second, if the biographer doesn’t share the same racial, cultural, or other marginalized background as their subject, it is incumbent on the biographer to address this through extensive and immersive research.

Third, in addition, the biographer who does not share identity or experience with their subject must also spend much time and energy reflecting on how their own identity relates to that of their subject and consider how it shapes or colors the lens through which they are viewing their subject’s life. This element, I believe, is most at risk of being absent from biographies by “outside” biographers.

Finally, even with all the research and self-reflection, ultimately, a skilled biographer who shares the same identity or background as the subject, will be able to yield certain insights that are unavailable to the biographer who doesn’t share these attributes.

My thoughts on who can and should write whose stories have been shaped by my own work on Lakshmi Shankar’s biography — a biography about an Indian American woman by an Indian American woman. For several years I was too intimidated to take on the responsibility of relaying Shankar’s life story because I felt I lacked the necessary credentials as a historian or as an ethnomusicologist. The sheer research required — to tell the story of a Hindustani musician necessitated relaying the story of Hindustani music — made me want to quit before I even started. Ultimately, it was the potential loss of her story to the world, given her advanced age at the time, and the cultural erasure of yet another woman of color, that urged me ever forward against all doubts. I realized that I had been focusing on all the ways in which I wasn’t qualified to tell her story, rather than on the ways I was.

First, my family had a close relationship with Lakshmi Shankar for most of my life. This both gave me access and a close perch from which to make observations of her both as an artist and a person. But I also knew that my close relationship could also be a hindrance, if I let the biography slip into hagiography. Second, Lakshmi Shankar was a South Indian woman who married into a Bengali family who became a lauded singer of North Indian music. Not many people, Indian or non-Indian, can understand the significance of the cultural, geographical, and gender barriers she transcended through her life and music. However, I was born to a Bengali father and South Indian mother and grew up steeped in both North Indian and South Indian music so I inherently understand the regional and cultural insularity of these worlds, the invisible barriers erected to both protect culture while keeping outsiders out. My own grandmother is of comparable age to Lakshmiiji, as I deferentially called Lakshmi Shankar, and they both were married as teenagers, yet their lives were so different. In many ways, my grandmother served as a reference point for what Shankar’s life might have been had she not taken the artist’s path.

Then there is the fact that I’m a writer who, before coming to writing, spent 15 years working on social change issues, including racial justice. So, in addition to depicting the key professional and personal moments within the narrative of her life, I have the ability to understand their significance in context to sociocultural history. I can illuminate some of the forces that worked in her favor as an artist, and the many forces that worked against her — including her cultural identity and gender.

While there can be other biographies of Lakshmi Shankar, my biography of her could only be written by me. Those with greater training and expertise in music might yield more nuanced musical insights while others who are historians might bring other historical facts to bear on her story. But there are certain insights and observations, given my shared cultural background and personal experience with Lakshmiji along with my own voice as a writer, that only I could have gleaned. Ultimately, it will be for readers and critics to decide the particular value of my role as narrator of Lakshmi Shankar’s story.

Some of the tension in recent conversations about authority, authenticity, and appropriation in writing comes from the emergent reality that many writers who for so long have been viewed, and have viewed themselves, as “inside” writers, now suddenly find themselves, for the first time, regarded as being on the “outside.” Where once there was no topic that was considered beyond their scope, they are encountering constraints in the form of questions about their authority and authentic tie to those narratives. Meanwhile, marginalized authors who have long been mining the life stories of descendants and figures in their communities often overlooked by history books only to now be “discovered” by the mainstream publishing sector, are justifiably defensive.

However, it is in itself problematic to have the starting point for this conversation be, “Who is permitted to write about what?” or “Why can’t I write about her?” Instead, it needs to start from a broader set of questions about the inequities in the publishing realm. “Who is permitted to write and be published? Whose stories are seen as important and elevated?” Beyond whether already empowered writers have permission to write about those outside their communities, the more critical questions are: “What is the particular value of a biographer who shares an identity or experience with their subject? What is the importance of authentic stories and voices in biography?”

If the current conversation were a story, it would be centered on the moment the writer walks into a room, leaving out any background on how they got there, who built that room, who else gets to walk into that room, who doesn’t, and why not. Ultimately, any lover of literature or history shouldn’t be satisfied with a story that is half-told and pre-ordained.

Beyond these ideological debates, the question of “Who has permission to write about whom” has ethical implications. In his book, Vulnerable Subjects: Ethics in Life Writing (Cornell University Press, 2004), G.Thomas Couser examines the issue of writing about others, especially those more vulnerable in society, through bioethical and anthropological lenses. He notes that, “What is at stake in the ethics of life writing is the representation of the self and of the other, which is always at once a mimetic and political act.” Couser goes on to state, “Such writing should not be beyond criticism, especially when it concerns issues of public moment…” He observes that rather than labeling valid criticism aimed at writers of others’ stories as “policing,” we should be concerned by the “policing” by “cultural gatekeepers” in the publishing sector who reinforce whose stories get told and who gets to tell them. Ultimately, Couser believes there needs to be “greater diversity in life writing, in two distinct respects: more kinds of lives represented and more kinds of representation.”

Speaking of Wiley’s unique artistic vision in rendering the subjects of his portraits, President Obama said Wiley “would take extraordinary care and precision and vision in recognizing the beauty and the grace and the dignity of people who are so often invisible in our lives and put them on a grand stage, on a grand scale, and force us to look and see them in ways that so often they were not.” It is evident that in portraiture, as in biography, who does the seeing affects who gets seen and how they are portrayed.