There is much to discuss — and avoid — on Twitter these days, but one tweet that has roused bookish folk and demands our consideration is about fake books.

On January 9, 2020, former Trump spokesperson Erin Elmore did a live interview with the UK’s Sky News in front of fake bookshelves, and a crease in the fabric incurred the internet’s wrath. In a tweet that received 30,000 likes and over 4,000 retweets in just a few days, Twitter account Bookcase Credibility (@BCredibility) smartly aligns fake books with fake news: “Credibility is hard to maintain when you forget to iron the creases out of your bookcase.”

The affiliation of bookshelves with credibility has a long history. From Buonaccorso da Montemagno’s 14th-century treatise Controversia de nobilitate — in which a poor bookish suitor gains credibility, and his beloved’s hand, through bookshelves that offer proof of an intellectual nobility, if not a noble birth — to Gatsby’s impressive library of uncut books that demonstrate his wealth and social mobility. The metonymic relationship of books to knowledge, class, and credibility continues into our contemporary moment with images like Elmore’s backdrop, which you can buy on Amazon for $16.60.

Fake books are nothing new. They have been part of the long history of the book since, at least, the 18th century when the craze for decorative (or “dummy”) spines went hand-in-hand with that of literary forgeries. Or, consider the genre of “blooks” (a portmanteau for “book-look”), objects that look like books but contain no pages. (Mindell Dubanksy, book conservator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, curated a wonderful exhibition and exhibition catalog of “blooks” for the Grolier Book Club in New York City in 2016; Dubanksy, 2016). Blooks have been around since the middle ages and surged in popularity in the United States during the 19th century. They attest to the need to keep books around even when we are (clearly) not reading them.

Andrew Piper reminds us that the physical presence of books — their thereness — matters: “It is this thereness that is both essential for understanding the medium of the book (that books exists as finite objects in the world) and also for reminding us that we cannot think about our electronic future without contending with its antecedent, the bookish past” (Piper, 2012: ix). We see this online everyday but certainly in the kerfuffle surrounding Elmore’s backdrop.

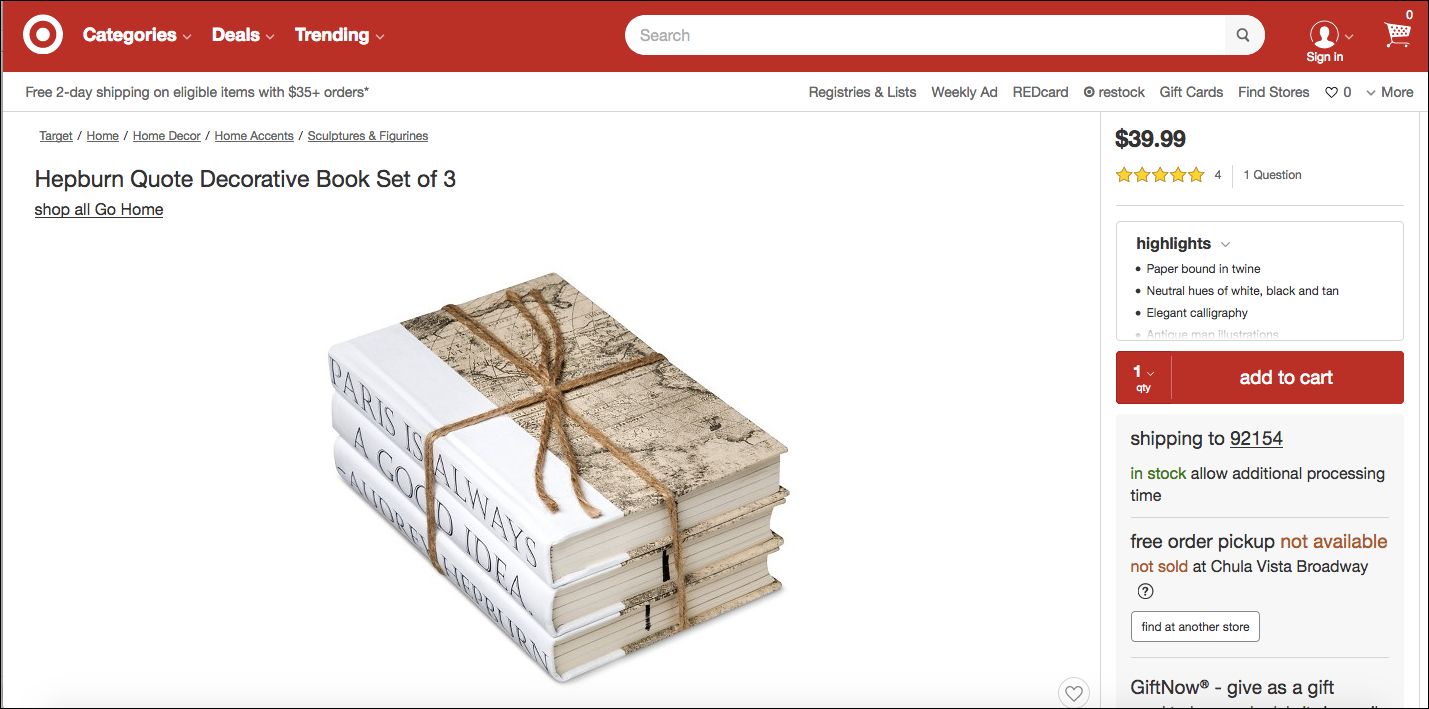

Digital culture takes fake books to new lengths. Consider how you can purchase a stack of “real” books — with covers, pages, and printed type — presented as a decorative bundle, tied together nicely with a twine bow. The stack below is sold by Target; the books are not intended to be untied, opened, or read. The spine of each book contains part of a famous quote. In this case, one book’s spine states, “Paris is always”; the next, “a good idea”; and the final book “-Audrey Hepburn.” When stacked, the bindings collectively spell out the quotation and attribution. We read these books not by opening them and considering their content but instead by reading their spines and viewing them as a stacked thing. Their thingness and their content have melded. A featured “highlight” in the item in its online description states that the bookish décor appears in “Neutral hues of white, black and tan,” allowing the fake books to blend in anywhere. They are décor and also signals of cultural capital and, yes, credibility.

“So-called fake things demand support systems,” Kati Stevens writes. “Fake flowers get real clay pots and vases; fake fruit real bowls” (Stevens, 2018: 10). Yet, fake books are not like fake flowers or fake fruit. Books index larger systems of social value and class stratification as well as the infrastructures that support them. Class, education, and a sense of credibility — the scholarly honesty and decorum that promises to do due diligence in research and to cite properly — are all bound up in the image of a book.

Bookcase Credibility’s tagline is “What you say is not as important as the bookcase behind you.” Books speak, and a collection of books are never just a silent background. Indeed, images of books and bookshelves proliferate online. Shelfies — self-portraits taken in front of bookcases — are a popular genre of digital imagery that serve as a means of constructing and performing identity, specifically a sense of self that is bookish and credible. As we see in the 1014 tweets (as of February 1, 2021) from Bookcase Credibility (produced in a startling short Twitter life of only 8 months), we still use our bookshelves as external, visible proxies to represent our internal selves.

That is why we see so much enraged fun taken in bashing the Trump spokesperson for her fake book backdrop: she has not taken the necessary care to even iron away the fabric creases that identify her bookish self-construction as fake. Real bookish folk know better and can read the fake books on the shelves.

Jessica Pressman is author of Bookishness: Loving Books in a Digital Age (Columbia University Press, 2020) and Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Diego State University. Web: jessicapressman.com. Twitter: @jesspres