2016 began with David Bowie losing his battle with cancer. Prince died in the spring. George Michael died on Christmas. Last Christmas. Carrie Fisher died two days later, on my birthday, as it happens. Her mother Debbie Reynolds’ heart broke planning her daughter’s funeral. She died the next day. I imagine exquisite drag queens and other unsung heroes greeting them all with cocktails in the heavens, saying, I know you still had work to do down there but we just couldn’t wait for you any longer. It’s so grim these days, watching them destroy themselves.

During the 1980s Faith World Tour, all my babysitting money purchased me one general admission ticket to the Shoreline Amphitheater. My first live concert. It seemed like magic to me that you could buy a ticket and see the man in the flesh. The steep, cold, muddy 16,000-capacity lawn was not what I was expecting; it barely qualified as seeing him. In my memory, I was there by myself, although this doesn’t seem possible (to my junior high buddy Linsey, if you were there with me, I apologize). I was too self-conscious to hang properly. I remember holding on to a spot at the railing, alone in the seething crowds. From there, we couldn’t see the big screen above our heads, but we could see the stage in the distance. George Michael was a beautiful gyrating speck.

A woman about my age now elbowed her way up next to me. She had come prepared, with binoculars. I think of myself now from her perspective: a short kid, barely a teenager, with off-brand fake Doc Martins and bad hair. Pressed against the rail, I stared intently and sang along, quietly, to every single lyric to every single song. I can still sing most of “Hand To Mouth.” When Michael died, one of my cooler punker friends posted that he liked George Michael’s “solo work.” I replied that I loved it all. No apologies. I can still sing “Heartbeat,” off Make It Big, by Wham!

“Mm-hm,” the woman with the binoculars said approvingly when George Michael turned around and the cameras focused on his ass. The stadium erupted in screams. As a junior high schooler, I was startled. I mean, I was in love with him, but I didn’t know this was what we were doing? I didn’t know we were allowed to scream out loud, especially about his ass.

Eventually, the woman next to me took pity and handed me the binoculars. I still remember the jolt of seeing his face, his beautiful stubble, the strain in his neck as he sang. The woman next to me was black, middle-aged, glorious in a wool coat and nice lipstick. She gave me my first experience of the defensive solidarity of pop music feminine fandom. She already knew what it took me so long to learn, that you don’t wait for permission to dance, to scream, to want, to love the things you love without apology. If they are going to judge, they are going to do it anyway. Scream. Bring binoculars.

George Michael, too, took his time learning not to apologize. He eventually became a defiant and outspoken advocate of LGBTQ rights, proudly refusing to sanitize his image for public consumption, calling himself a “dirty filthy fucker.” He was dirty, and glorious, and he was also the sweet face of “Last Christmas” and the boy wonder of Wham! It was a process for him, to get to that place. The gay community has and rightly will continue to lionize George Michael as their own. Coming out publicly, as a political advocate, was something he did over time at a high price in a difficult era. His first lover died of AIDS. He carried guilt because he felt that his lover would have gotten better health care, right at the beginning of combination therapy, if he hadn’t been trying to avoid the tabloids. These were George Michael’s most important battles, and I don’t speak as a representative of the gay community. But I do count myself part of a larger community of people who feel like we can’t spare a single voice, a single ally, just now. Heartbeat, heartbeat, how could you leave me here.

George Michael’s long coming out, his ferocity, also did work on behalf of pop and gender more broadly. He spoke with gratitude and pride of his loving open relationship with a man. But he also claimed some femininity, eventually he called himself bisexual and said he looked at women first when he walked into a room because they tended be more glamorous. I’m so grateful for that, because I kind of took it personally when he disavowed schoolgirls in Freedom ’90. I was every little hungry schoolgirl’s pride and joy…he sang. When you shake your ass, they notice fast, some mistakes were built to last. As if schoolgirls’ pride and shaking your ass unapologetically were mistakes! But he was suicidally depressed in the 90s. Freedom ’90 is a lifeline of an unapologetic dance ballad that I still adore. George Michael fought through the idea of ever having been a mistake. He came to terms with who he loved and who loved him, with unstable gender categories, and with the torrents of emotion that he inspired in young girls. None of it was a mistake, George Michael. The only mistake was leaving too soon. Listen Without Prejudice: Volume 1 still doesn’t have a volume 2.

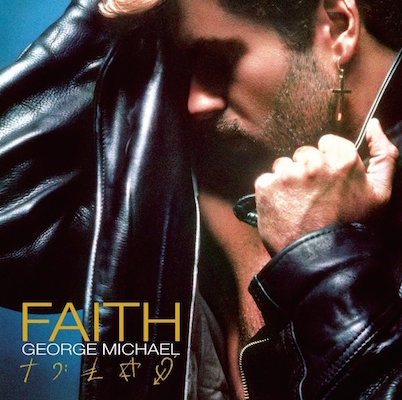

Every major rock star from Elvis Presley on has banked on the unqualified adoration of legions of girls, especially at the outset. But in public discourse and in male-dominated rock criticism, disavowing girls has long been part of being Rock, capital R, and not pop. Rock and rock criticism embrace the narrative where teen idols get serious by explicitly moving past girlish fans. George Michael’s white blazer and feathered hair and catchy hooks, his gay-seeming qualities and his little-girl-pleasing qualities, these supposedly made him not-rock, not-serious. When he made Faith and donned a leather jacket and grew some stubble, he was interpreted as ditching both teen idol-dom and gayness for serious rocker status.

Part of the beauty of George Michael, then, is that his out-loud process of coming to embrace social justice alongside pop also re-included girlishness. In 2004 he told GQ, “I never minded being thought of as a pop star. People have always thought I wanted to be seen as a serious musician, but I didn’t, I just wanted people to know that I was absolutely serious about pop music.” I’m not sure I believe him, that he never wanted to be seen as a serious musician, which he always was. But I believe him that he lived his transformations in public, and that he came around to pop. He came around to being a grand unapologetic icon for all, including the hungry schoolgirls, to embodying a kind of big tent pop inclusivity. As we enter a new age of fear for everyone who feels different, queer, girlie, or in need of better healthcare, this is part of what makes his death feel so unjust.

Everyone must, at some point in some way, mourn their youth and mourn their pop stars. But it is by now a cliché to say that 2016 has made us feel robbed. I would like to ask Madonna, who is still out there refusing to apologize for being a woman, to please watch out for falling pianos. Bruce Springsteen has already written a thoughtful memoir about how his masculinity was an act — Bruce, take your vitamins. What will we do without George Michael, Prince, and the real Carrie Fisher in a franchise just now taking baby steps with feminism? My girlfriends were sending around this picture of Carrie Fisher in the ‘70s:

Her beauty was always in her ferocity, which she had even when she wasn’t holding a Star Wars gun.

Part of the pain of 2016 has been the feeling that we’re losing people early, before they got to write important last chapters, the very people who helped us know how to be fierce and dance and raise our voices without apology, the icons who helped us, at a time when we need them most.

Here are some of the serious pop lyrics that I still know to “Hand To Mouth”:

But no one told me that the gods believe in nothing

So with empty hands I pray

And from day to hopeless day

They still don’t see me

RIP George Michael. All the dirty filthy fuckers miss you already.