By Sunil Bhatia

When I was in 6th grade in a class of about 40 students at a small Catholic English-language school in the Indian state of Maharashtra, the school’s Vice Principal, Father Victor* (always wearing a spotless white robe), was making his usual rounds to different classrooms.

Each teacher had distributed report cards and Father Victor randomly picked on students for tardiness or wearing a disheveled uniform to ask them a question or chastise them.

That day it was my turn.

He pointed his cane towards me. So I obliged and stepped outside the classroom.

“How many subjects did you fail in?”

“None,” I replied. As soon as I did, I saw his huge, fat hand come toward me and land on my face.

I dropped to the ground screaming, “No, no, I did not fail in a single subject. None. None.”

Father Victor looked down at me. He responded that my “none” sounded like “one” and that it was my fault. “You need to learn to pronounce your English words properly.”

Father Victor “hailed” me as a new postcolonial subject of the bygone British empire that day, transforming me from an individual to a person with a postcolonial identity. All the agents of my schooling had imposed colonial standards on my imagination and my evolving identity. For most of my school years, I received many such fundamental lessons about the superiority of British culture and language.

It was a simple definition of power. And it was mandatory.

Anyone around me who had money, a house, a car, a job and status, and had traveled abroad could speak in English. The lower caste or Dalits, the urban poor, the maid servants, the rickshawallah, the postman, and two of my uncles were not powerful. They did not speak English.

Those who spoke English belonged to a different and often superior caste. Those who were poor and educated in their native languages were called ghatis – a pejorative word for the working class non-English speaking folks.

Becoming postcolonial, however, was not just about the English language.

My parents wanted to make me a contender, a sahib and not a ghati. So they put me in an English language Catholic school. I only discovered I had a postcolonial identity when I studied postcolonial theory as a graduate student in the U.S.

What I learned is that the affix ‘post’ in postcolonial does not mean that there was a neat separation between the former European colonial powers and their colonized subjects.

We may live our lives forward, but understand it retrospectively. My consciousness about the world was fundamentally defined by the eviscerating legacy of colonization.

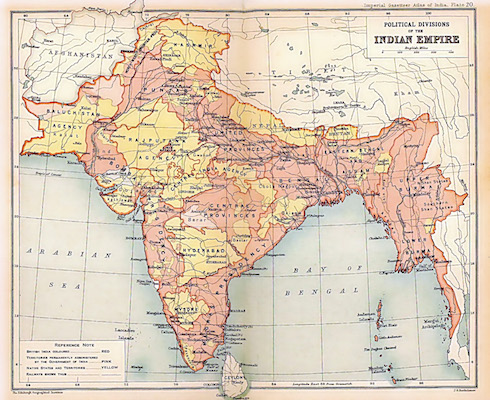

Today, Brexit has elicited a nostalgia for Empire 2.0, a longing for a time when Britain ruled the world through the brutal mechanisms of colonialism and genocide.

As television dramas such as Downton Abbey and Indian Summers romanticized the colonialism of the “British Raj” and engage in historical amnesia, it might be worth remembering that the call to White Man’s Burden to rescue darker people in the “uncivilized” places unleashed terrible murder and mayhem of native people.

A 2014 YouGov poll shows that 60 percent of the British public expressed pride in the legacy of British empire and 50 percent of them thought that the former colonies were better of due to colonialism. Paul Gilroy, a professor at King’s College in London and a scholar of cultural studies, has described the British public’s longing for the empire as postcolonial melancholia, where the “wounds of imperial domination” have been mystified or forgotten.

Britain’s imperial rule of India was racist and ruthless as it oppressed, imprisoned, and tortured Indians over 200 years. Its policies created famines that killed over 35 million Indians. Another million people died and more that 13 million became displaced during the violent and tragic partition of India in 1947.

In his new book, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India, author Shashi Tharoor documents Britain’s rapacious looting and destruction of India. He writes that the British Raj created social and legal institutions based on racist laws, dismantled pre-colonial systems, enacted divide and rule policies, implemented protectionism and a punitive tax code for the natives, curbed free speech and imposed arbitrary sedition laws.

The British called my ancestors primitives, rude, backward, lazy, ignorant, and “a beastly people.” Yet I was taught that British and European culture and its people were more correct, legitimate, and superior to Indian culture and history. These were my very first lessons in internalized colonial oppression that I accepted as normal.

Edward Said’s book Orientalism shows us how the colonists used the power of science to create an ethnocentric and racist “archive” of knowledge about the Orient so they could colonize the space, body and mind of the so-called native subjects.

Ashis Nandy, a political theorist, warns us that this second form of post-colonization is as dangerous as the first kind because “it creates a culture in which the ruled are constantly tempted to fight their rulers within the psychological limits set by the latter.”

The South African, anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko was right: mental emancipation or psychological liberation is a necessary perquisite for achieving political freedom.

Decolonization is a long struggle. Many years have passed since I felt Father Victor’s slap, but the devastating effects of colonization continue to have a haunting presence in postcolonial nations and on their citizens.

*Name has been changed