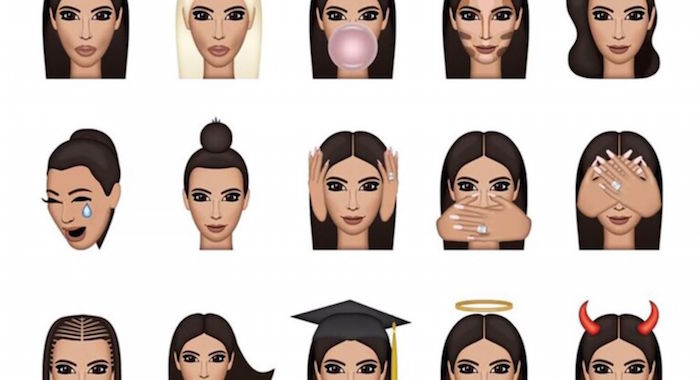

A little over a year ago, when entrepreneur and reality television tycoon Kim Kardashian debuted the first wildly popular line of celebrity emojis named Kimoji — an app that packages personalized emoticons and digital stickers for smartphones — a rumor propagated by online entertainment sites and the star herself claimed that Kardashian had broken Apple’s app store. The rumor proved false, but the publicity helped. Even more, people liked the Kimojis, which included risqué curves, Yeezy sneakers, a corset, a cannabis leaf, a car with suicide doors, and a now-viral image of Kardashian’s face with a pixelated tear placed below a kohl-dipped eyelash.

Not just pop singers and the beau monde of reality television are included in the mania surrounding celebrity emojis. In the past year, icons like Hillary Clinton, Ellen DeGeneres, and even Drake’s dad all have rolled out their own emoji packages. Walking along the eastern edge of Central Park this fall, I saw a van plastered with an ad promoting 95-year-old designer Iris Apfel’s line of literal fashion icons you can purchase on your phone and text. That was the moment I knew the sensation had transcended trend into the realm of celebrity survival strategy.

In early December, the Museum of Modern Art acquired the original emojis from 1999, a move that decidedly ratified emoticons’ place as legitimate art. But are celebrity emojis art? Certainly, like art, customized emojis serve aesthetic purposes as well as political ones, and often muddle the line between self-expression and self-promotion. This is evident in apps like Kimoji, which is simultaneously a template for product placement, an accelerator for the celebrity’s personal brand, and a kit of images that undeniably afford some vestige of happiness. If MoMA’s acquisition reinforced the idea that Kardashian’s invention was art — shoes, cars and Solo cup emblems becoming Warholian still lifes in a downloadable, textable oeuvre — it also emphasized that emojis are frequently influential consumerist tools. Often, there is little difference between the two.

Celebrity emojis’ potential for empowerment has been well-documented, but one controversy suggests their future could include weaponization. Recently, it was discovered that Donald Trump basically blacklisted Jack Dorsey from a Trump Tower tech gathering because of the Twitter CEO’s refusal to help disseminate #CrookedHillary emojiss on the president-elect’s go-to social media platform. According to Politico, the emojis would have depicted illicit cash transactions. It says something that Dorsey’s refusal to cooperate created such agitation within Trump: within a politics where symbolism reigns, the agitprop would have carried unfortunate power. What would happen if anyone could create a pixelated cartoon of you and disperse it amongst the universe? Despite the repeated comparison to hieroglyphics, emojis — and especially ones with specific “identities” — are not apart of neutral alphabets, waiting to be imbued with the sender’s meaning. But then, neither are hieroglyphics. Like all language, emojis are freighted with the subtle violence narrative and context can enact.

“Emoji are ideal for representing the trappings of celebrity culture, from martinis to paparazzo attacks, all within a normative, cartoon vision of wealth and fame,” wrote social media scholars Luke Stark and Kate Crawford in an academic article titled “The Conservatism of Emoji: Work Affect and Communication” that appeared in the journal Social Media + Society in 2015. Because these animations frequently seem to reinforce consumerist ideals, the industry of celebrity emoji raises the question: Are famous-people emojis meant for expressing feelings and ideas to each other through unique yet relatable imagery, or do they simply serve as a way for the wealthy and famous to better hone, market and legitimize their names?

Mathieu Deflem, a professor of sociology at the University of South Carolina, told me that celebrity emojis can fulfill both roles of solipsism and inclusion. “On an inter-personal level, celebrity emojis are about communication,” Deflem says. “Such interactions are horizontal, among equals. Using a celeb emoji would strengthen that idea that people can use, or abuse, a celeb to make things fun. But celebs using them themselves or promoting them brings in a vertical dimension, which is quite different.”

As Stark and Crawford mention in their article, which was published shortly before the current boomlet of celebrity emojis, electronic glyphs allow us to inject character into plain text, giving users “a quick and efficient way to bring some color and personality into otherwise monochrome networked spaces of text.” The authors even find that the use of emojis can be an “emotional coping strategy.” As they point out, “Emoji create new avenues for digital feeling, while also remaining ultimately in the service of the market.”

In addition to easing emotional labor, celebrity emojis can potentially raze the border between your own persona and that of the celebrity. Apps like Chymoji or Kimoji effectively encourage us to mortgage our own personalities in exchange for a readymade, pre-approved one; a playful phenomenon suddenly feels less harmless. The escapism these emojis offer is enabled by the false belief that the user is engaging with their own individuality. Perhaps this is slightly reminiscent of religion. Certainly, the obsessiveness that drives many celebrity emojis users requires the same faith and fantasy found in worship. After MoMA announced that it would be exhibiting the original set of emojis from the 90’s, Amanda Hess in the New York Times likened the smartphone to a “tiny little collection of modern art,” but it seems some phones might closer resemble an altar. Remember that celebrity derives from the French word for “solemn ritual or ceremony.”

According to a 2015 study conducted by the emotional intelligence agency Emogi, it’s a rite that the majority of the online community are participating in, with 92 percent using emojis. That same study revealed, contrary to the belief that this specific genre of communication is reserved for tweens and millennials, that all ages are likely to use emojis. Emogi noted that women are more likely to use emojis, arriving at the strange and unelaborated conclusion that they found them more “enriching” than men.

Emojis have historically existed in matrices of white heterosexuality, Roxane Gay pointed out in a 2013 essay titled “The Unbearable Whiteness of Emoji.” But when public figures like Ellen DeGeneres, Hillary Clinton, and Gabby Douglas are able to alchemize their seemingly-intimate selves through electronic self-parodies, they can, in small ways, personally reaffirm their presence and even specific value and belief systems in a world where minorities face visual underrepresentation.

For beholders of celebrity emojis, the real world and the emoji world often converge, says Dez White, the creator of Chymoji and an owner of company that makes celebrity emojis. White offers a parable by citing Tamotions, an emoji she produced in October centered around television personality Tami Roman, whose Instagram video series “Bonnet Chronicles” — which consists of simple one-minute jeremiads featuring Roman wearing a bonnet — have become an internet sensation. White told me that Tamotions became an extension of the Instagram sitcom, itself of course an extension of Roman’s real life. “Emojis are about expression,” White says.

Maybe. But perhaps celebrity emojis are destined to live in the gray area which, really, nearly all art inhabits: somewhere between the world of inventive ideas and the world of monetized, self-celebratory aphasia.