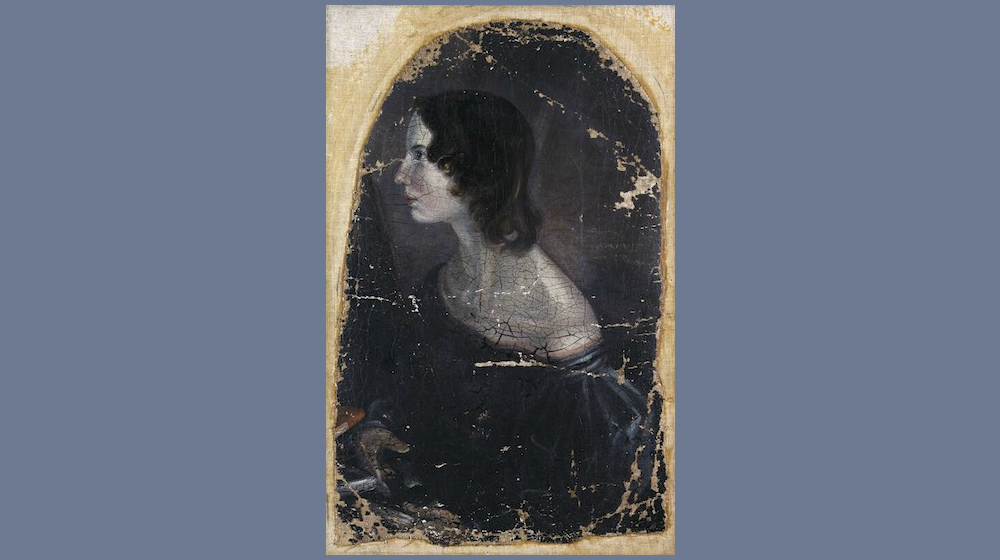

The face is that of a young girl; delicate with brown hair framing small, rather pinched features. There is not even the hint of a smile, although she knew the artist very well. She is pale; the eyes may be a light green or gray. Her gaze seems intense and, significantly, is directed away into the distance — not the conventional direct pose for a portrait. It is only a profile, permitting minimum engagement. The sitter appears remote because in life, she was detached. This is a solitary, taciturn individual no one really knew, not even her siblings with whom she lived. Her closest relationships were with birds, dogs, and cats; she collected stray animals and had no friends; she left few letters, only dramatic, self-revelatory poems. Emily Brontë was about 15 years old when she sat for the ghostly study, possibly a fragment of a larger work, painted by her brother Patrick Branwell, the one person she would always forgive, and she was known to be most unforgiving.

The image hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London, where millions of visitors have peered closely at it over the years, wondering at this singular visionary, whose complex and contentious only novel, in which English Gothic meets German Romanticism, exudes such terrifying imaginative energy.

Why did this girl, the fifth child of six — five daughters and one son — born on July 30th, 1818 — to an Irish clergyman, whose wife Maria’s death resulted in all the children being raised by his sister, Elizabeth, a staunch Methodist, why did she write such a powerful, quasi-Shakespearean tale, a savage yet spiritual tract, about exasperated, dangerous, and supernatural passion?

Growing up in an isolated parsonage with her sisters and brother, all of whom were sickly — the two eldest sisters had died as schoolgirls — what made her think of evoking domestic tension spanning the generations? How did she conjure up a Heathcliff, with his “half-civilized ferocity” “and eyes full of black fire,” a character who makes the merely handsome Mr. Darcy appear somewhat petulant?

Where could Heathcliff, such a tormented soul, driven by revenge, have come from? What experience could have possibly helped the wary, introspective Emily Brontë — whose mother had died when the future writer was three years old and gathered at the deathbed together with the other children, all watching on and waiting — grasp the frenetic, emotional turmoil that sustains Wuthering Heights?

Aside from a brief stint as a child at the Clergy Daughter’s School; some months when she was 17 enrolled at a school where Charlotte was teaching; a stay a few years later in Brussels, where she discovered German literature; and her unhappy four month period as a student-teacher, giving piano lessons to terrified pupils, Brontë lived her short life at the Haworth parsonage, on Yorkshire’s moors, a harsh, demanding environment exposed to relentless winds, a place where winter seems to last longer than it does elsewhere.

By 30, one year after the publication of Wuthering Heights, she was dead, dying of tuberculosis, joining Branwell at whose funeral three months earlier she had contracted a chill. Only on her last day of life did she agree to see a doctor. It was too late.

Her sister, Charlotte, who famously feared, disliked, and did not understand Wuthering Heights, recorded Emily’s final hours: “She sank rapidly. She made haste to leave us. Yet, while physically she perished, mentally, she grew stronger than we had yet known her… I have seen nothing like it: but, indeed, I have never seen her parallel in anything. Stronger than a man, simpler than a child, her nature stood alone.” It is a beautiful elegy. Even so, Emily Brontë was not a naïve, inspired rustic; she was a sophisticated and deliberate artist.

Ravaged by consumption, she fought death like a warrior of old. On the evening before the day she died, Brontë collapsed while feeding the dogs. The next morning, she insisted on her habitual seven o’clock rising and combed her hair by the hearth in her bedroom. The wooden implement slipped from her fingers. She was too weak to pick it up. She dressed and made her way downstairs, gasping for breath.

By noon, she could barely speak. She was carried upstairs. In Charlotte’s words, “turning her dying eyes reluctantly from the pleasant sun,” Emily Jane Brontë, poet and loner, died at two o’clock in the afternoon of December 19, 1848. Her dog, Keeper, had kept vigil by the bedside. If Brontë’s belief in life after death was as strong as her defiant masterpiece suggests, her spirit no doubt continues to patrol the moors.

How to explain the unearthly bond between Catherine and Heathcliff in a novel in which — despite the underlying violence, and the wealth of talk about nature, passion, and eternity — as mundane a concern as social aspiration is one of the major themes? It is Catherine, admittedly tempted by the genteel world Edgar Linton represents, who endeavors to explain her feelings to the central narrator, staunch, candid Ellen “Nelly” Dean, the ever-present, talkative, and almost unshockable housekeeper whose interest in the anguished players helps piece together the story.

In one of her milder moments Catherine, although speaking to Nelly, appears to be unraveling her thoughts and feelings aloud; perhaps she may be addressing humanity in general when she says: “I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation, if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger: I should not seem a part of it. My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods; time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being.”

Poets and singers, painters and musicians have striven to articulate the elevating, tormenting, and destructive sensation known as passion. Emily Brontë conferred this fierce eloquence on a character named Catherine Earnshaw. The choice of the name Earnshaw, with “earnest” as its root, could be debated. Yet Catherine is not her creator’s alter-ego. The reality is far more devastating: Emily Brontë is Heathcliff. Only through his rage, grief, and obsessive, despairing need to right wrongs done to him and by him — to defy existence itself — do we begin to approach some understanding of what it was to be her.