When I received a scholarship to the American Booksellers Association Children’s Institute in Pittsburgh, I was eager to not only take in all the bookseller programming the conference had to offer, but to also explore a city I mostly knew through my father’s lifelong love of the Pittsburgh Steelers and mine of Mr. Rogers. Preparing for the trip, I researched authors who were from, or lived in, Pittsburgh (as I generally do before traveling anywhere) and was amazed at the wealth of writers on offer. I decided to spend my time with the ghost of Nellie Bly, who got her start as a writer in Pittsburgh and took on the pseudonym under which she’d write for the rest of her life.

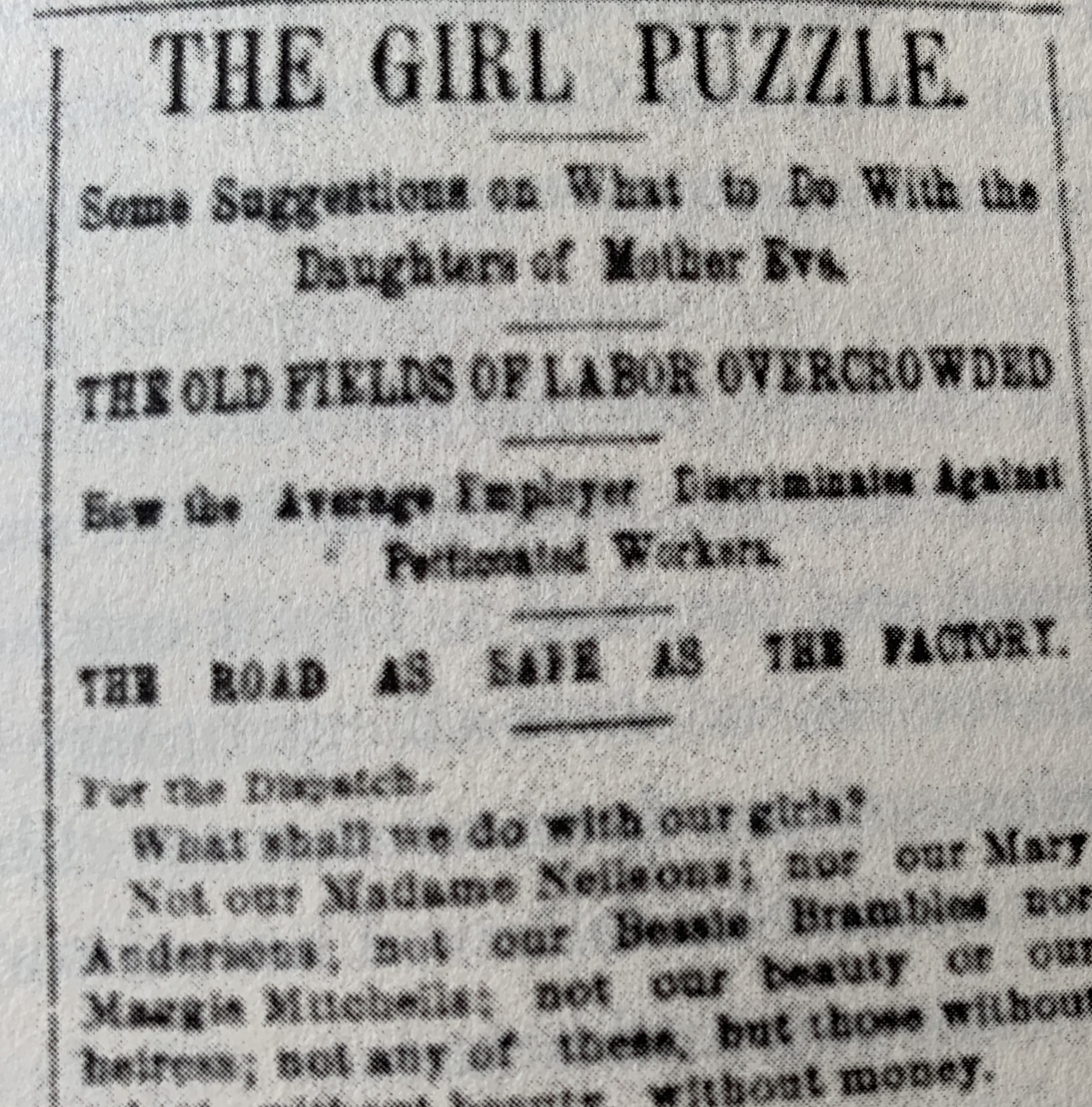

Born Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, the journalist got her start in Pittsburgh by writing a letter in response to a column in The Pittsburgh Dispatch. When the editor decided to hire her on after Cochrane’s response, he bestowed upon her the nom de plume Nellie Bly, taken from a popular song at the time.

The column that sparked Nellie Bly’s first printed writing was about a father’s despair over his unmarried daughters and what they might do without husbands. Many women wrote in response to his piece, but it was Bly’s letter that caught the eye of the editor and secured her a writing job at the Dispatch. Unfortunately for us, most of her writing from that time is not widely available, as the Dispatch closed in the early 1920s, long before they could make their archive searchable online. Conveniently, Penguin has included that first piece of writing in their collection Around the World in Seventy-Two Days and Other Writings.

I wanted to read more of her early work, but “The Girl Puzzle,” her first column is a stunner and full of more prescient insight and wisdom than I had anticipated. Much lengthier than today’s letters to the editor, Bly (who signed this letter “Lonely Orphan Girl,” a name I can appreciate) assessed not only the claims and concerns of the original column, but also delved into an area that deserved to be analyzed: that of working class women who were ignored in conversations about female vocation because they had to work instead of marrying a man who could support them.

Armed with “The Girl Puzzle,” I searched for a suitable place to meet with the ghost of Nellie Bly. She wrote for the Dispatch from 1885-1887, and much of Pittsburgh has changed since then. The Dispatch building was on 5th Street near where the Pittsburgh Penguins now play, but heading west on 5th Street takes people over to Market Square, which, while revamped in the 2000s, dates back to colonial times. It’s also home to The Original Oyster House, the oldest bar/restaurant in Pittsburgh, dating from 1870.

It’s a no-frills bar and restaurant, and I snagged a stool at the counter and asked for an Iron City beer, a brewer that’s been making beer since 1861, with perhaps a gap in their continuity during Prohibition. While it was nearly impossible to determine if Nellie Bly had herself sat there and had a beer, I trusted that the 140 years of service at the restaurant meant that plenty of ghosts were hanging around, and that at some point in her years in Pittsburgh, Nellie Bly had stopped in for oysters and beer.

With a cold beer in hand, I pored over “The Girl Puzzle,” and felt as though a young, impassioned Nellie Bly was, in fact, sitting next to me. Her response is a plea for equal opportunity and pay for women, and an appeal to well-to-do women to have sympathy for their poor sisters. She writes, “How many wealthy and great men could be pointed out who started in the depths; but where are the many women?” She decries the way that our American rags to riches tale excludes women, who are barred from many opportunities to work their way up from an errand runner or clerk to a respectable, well-paying position.

While things have changed for women, there is still so much inequality that Bly’s words continue to ring true. As she discusses what jobs would be filled well by women, she writes, “It is asserted by storekeepers that women make the best clerks,” and suggests sending women on the road as traveling salespeople. But, she adds, that it only works if the women are treated equally: “unless their employers would do as now — give them half wages because they are women.”

Even today, some women make half a man’s pay for equivalent work, but women of color are often paid even less. The inequality Bly saw in the 1880s has not yet been alleviated, despite fair pay laws and the continued women’s movement. It is both depressing to know that is the case and encouraging to know that there are centuries of women who saw that problem and did what they could to change it. Bly had her pen, and other women have used their voices and bodies to win suffrage and campaign for more fair treatment.

With that pen, she advocated throughout “The Girl Puzzle” for better consideration for poor women from both their wealthier sisters and all those who would wish to practice philanthropy. She suggests, “Instead of gathering up the ‘real smart young men’ gather up the real smart girls, pull them out of the mire, give them a shove up the ladder of life, and be amply repaid both by their success and unforgetfulness” of those who helped them.

In that plea, I see the kernel of what would one day become educational programs aimed at girls, like the many STEM-focused enterprises now at work encouraging girls to become engineers and programmers. It is a long journey from 1885 to the present, and it feels like while much progress has been made, there is more to do. Thank goodness for all those between her time and ours who have thought it worthwhile to encourage and educate girls.

I think too about why Nellie was writing and for what audience. It’s hard not to think about that when seeking out a place she might have gone in her time in Pittsburgh. She spent her earliest years in Cochran Mills, named after her family, but after her father’s death there was a steep fall from financial security. The way she signed her letter, Lonely Orphan Girl, serves as an indication of how she saw herself. In the gap between what Erasmus Wilson wrote to the “Anxious Father” in search for advice for what to do about his daughters and how Bly saw herself, she saw a need for all those in her position to be represented.

Marriage was not then, nor is it now, a panacea for all a woman’s problems. As often happens when I sit down with a literary ghost, I find not only guidance for a writing career, but for the whole of my life. I am fortunate enough to be an educated woman who provides for herself through her labor — the exact fulfillment Bly writes about. While I would not mind a husband, I have no expectation or need to have one to support me and give my life meaning. Knowing that Bly felt the same way and that she valued education and career opportunities more, I feel even more validated.

I also see in her work a path to success in writing. She wrote a letter to the editor, wanting to express the difference between Wilson’s vision of womanhood and her own, and it turned into a long and successful career for a trailblazing woman. Making the effort to have her voice heard set the stage for what she would do throughout the years, whether as a foreign correspondent in Mexico, committing herself to a mental institution, or striving to beat Jules Verne’s fictional Phileas Fogg’s time around the world. That first step — putting words to paper and sending them to an editor — opened the first of many doors she would step through into new opportunities. She gave herself the same push and freedom to advance that she asked for her sisters.

I knew about Nellie Bly’s investigative journalism, and of her world travels, but I did not know that she got her start talking about the female situation. In communing with her and the words she left behind, I felt empowered to use what resources are available to me to do something similar. What that looks like, I don’t yet know, but I know that she is one ghost it is impossible to encounter without being spurred on to new action. To quote Bly one more time, “Let them forego their lecturing and writing and go to work; more work and less talk.” Let us hear that commandment passed down over the last 130 plus years and go to work to change the world.