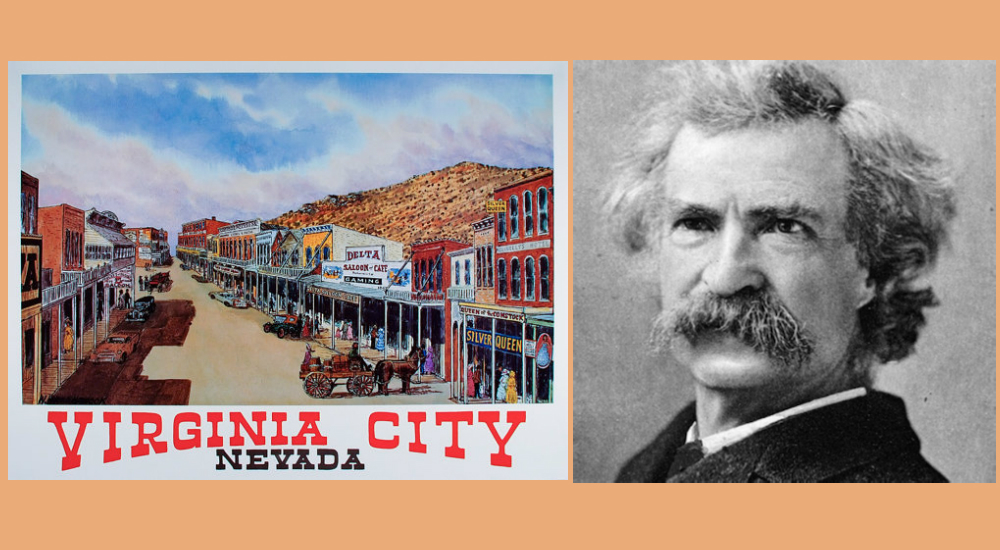

Just outside my hometown of Reno, Nevada is a mining town almost untouched by time, aside from the crowds of tourists and shops that provide them with souvenirs and knick-knacks. The sidewalks are still boardwalks and there are hitching posts for horses outside most businesses where on previous trips, I’ve even seen people actually hitching their horses. It was while writing for a local newspaper in this little boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada, that Samuel Clemens first took the name “Mark Twain.”

During a trip home to visit family, I wanted to spend some time with a literary ghost, so I made my sister drive me up to Virginia City so we could go drink with Mark Twain in all the bars we could. It was a bit of a literary bar crawl, as so many of the saloons there claim that Mark Twain once drank there, along with other luminaries of the Comstock Lode, the underground vein of silver that made this town the fastest growing city in Nevada at the time.

As Twain wrote in Roughing It, his chronicle of his time out West, “Six months after my entry into journalism the grand ‘flush times’ of Silverland began, and they continued with unabated splendor for three years… Virginia had grown to be the ‘livest’ town, for its age and population, that America had ever produced.” It has quieted some, but there are still bars lining the streets and the opera house still has shows regularly, even though they no longer boast talent like Jenny Lind, the Swedish songbird who took America by storm in the 19th century, and who performed within those walls.

The oldest saloon in Virginia City has been updated, but not in the hipster fashion it would have been in a bigger city. It serves a clientele of tourists and locals alike, and I found myself feeling like a cross between the two — an out-of-towner that had once been from those parts. Originally opened in 1862, the Washoe Club reopened in 2010, but has held onto many of its fixtures from the 19th century. The bar back feels authentic to 1862, even as a more modern cash register sits alongside an antique. When it was founded in the 1860s, it was a private social club, graced by the newly minted millionaires of the silver mines and their guests, like Mark Twain himself. A sign painted on the wall boasts of that legacy. It also is purported to be haunted (complete with an exhibit devoted to its ghost), so it feels like a perfectly fitting place to commune with a literary ghost.

In Roughing It, you can see Mark Twain develop his purpose as a writer. It was encouraging to me, as a writer finding her purpose, to witness someone undertake the same journey that I am on. Twain details his path to becoming the city editor at the Virginia City Daily Territorial Enterprise, counting previous jobs he’d held, including grocery clerk, riverboat captain, pharmacy clerk, and my favorite, a bookseller who couldn’t find time to read while manning the shop. Same, Mark Twain, same. It’s reassuring to see that one of the great American writers took a while to find his way to writing, and that, according to him, he kind of fell into it. He had written letters to the paper which were frequently published, and they asked him to come be their city editor. I think a lot of writers today, myself included, would be thrilled to have someone ask them to come be a professional writer, and for Twain, it established his raison d’etre. It’s likely that he did more to get that position, but he recounts the experience with his trademark wit.

Twain writes about the difficulty in filling his columns when he started writing for the Enterprise, and his gratitude for the murder that happened his first day, which gave him something to write about. He filled his required columns with that incident and a few others, and wrote, “When I read them over in the morning I felt that I had found my legitimate occupation at last.” That creation and confirmation of vocation is something I understand, and am glad to know that Twain had a moment of realization that writing was to be his career.

I settled in to read about Virginia City in its heyday with a whiskey, thinking it was the most rough and tumble mining drink I could have. My sister, very kindly, let us sit in silence so I could read and drink with Mark Twain, and allowed me to read aloud to her as I found passages I particularly enjoyed. It was a nice change of pace to have someone with me as I visited with a ghost, so that the excitement I feel when I read and connect with an author in a place they had once frequented could be communicated immediately.

Twain captures the thrill and seemingly endless growth of Virginia City at its peak. He writes:

Money was as plenty as dust; every individual considered himself wealthy, and a melancholy countenance was nowhere to be seen. There were military companies, fire companies, brass bands, banks, hotels, theaters, “hurdy-gurdy houses,” wide-open gambling palaces, political powwows, civic processions, street fights, murders, inquests, riots, a whiskey mill every fifteen steps, a board of alderman, a mayor… a dozen breweries and half a dozen jails and station houses in full operation, and some talk of building a church. The “flush times” were in magnificent flower!

His facetiousness regarding the abundance of vice and its corresponding institutions compared to the idea of building a church is part of his famous humor, and it’s a delight to see it on full display here in his burgeoning career.

Despite having grown up in this area, and knowing about Roughing It for as long as I can remember, thanks to my mom, I had never read it. It was only now as I thought about making an intentional pilgrimage to the places of Mark Twain’s history in Virginia City that I decided it was time to pick up my mom’s copy. It was easy, on previous trips, to find locations tied to Twain, thanks to the abundant signage around the town marking where he and other luminaries had once visited or dined or drank. Now though, I was eager to see Virginia City as it was during Twain’s time here. His descriptions brought to my mind vivid images of dusty men straight out of the mines, teeming the streets on their way to spend the abundant money of the mining boom.

After finishing my whiskey, we migrated down the street to the Silver Dollar Saloon, famous for its mural of a woman whose dress is made of Virginia City silver dollars. I was there for another reason — it is housed in the building that was once the home of the Enterprise, and where Twain worked when he wasn’t out on assignment collecting the news and hobnobbing with the locals.

Both bars were dim and quiet in the early afternoon on a Saturday. Most people strolling the streets weren’t ready to drink at noon, I suppose, but I had a mission, so Twain and I were sipping whiskeys for lunch. Walking down the street, it was odd to go from Twain’s version of crowded, boisterous Virginia City to the modern day. Tourists have replaced miners, and while the boardwalks were crowded, it didn’t have the same energy or crowdedness that Twain had put into my mind.

In the Silver Dollar, I got another drink, and settled in to read more about Twain’s early writing career. I wanted to find advice from him to me, and in his recounting of advice from his first editor, I found a good lesson for my own writing. “Never say ‘We learn’ so-and-so, or ‘It is reported,’ or ‘It is rumored,’ or ‘We understand’ so-and-so, but go to headquarters and get the absolute facts.” It’s great journalistic advice, and a sharp reminder to me in writing nonfiction. Twain is an exemplary storyteller; I found myself falling deep under his spell as I read, caught up in the tales of a boomtown, rather than often taking the time to step back and analyze how I was reading his work. A couple whiskeys and a lot of stories later, my sister and I examined the Silver Queen’s dress, and went back out into the bright midday sunlight.

Now that the Comstock Lode no longer produces droves of silver, the town has to survive somehow, and its historic preservation is the key to drawing crowds of visitors willing to spend their money on tours and fudge. No judgment, of course, as I too have a box of fudge as a delicious reminder of my time in Virginia City.

What I also have is a deeper connection to the greatest literary representative of the place where I originate. Other authors have sprung up from Nevada’s chalky soil, but none so important or lauded as Twain. I know that I will always live in his shadow, and that’s still a pretty great place to be.