In the swarming subway station at 42nd street, a woman wore rainbow leggings patterned with kitty faces. She held her poster board in a large plastic bag: “I am the daughter of a refugee. I am the American dream.” A mother held her daughter’s hand and a sign — “Respeta Mi Existencia o Espera Resistencia!” — in the other. Police lined the steps to the street, high-fiving protesters as we streamed into the street outside Grand Central Station. Scattered women wore pink knit “pussy” hats in rebellion against Trump’s vile comments about sexual assault. I wore my commemorative Barack Obama 2008 t-shirt in a feeble attempt to transport myself back to the early days of his presidency, attending his rallies with my mother and volunteering for his campaign.

The entire stretch of 42nd Street was suffused with more than 500,000 zealous marchers at the New York sister march of the Women’s March on Washington. By noon, people of all ages, genders, and nationalities stood squished between police barricades. They smiled and cheered under waving posters. A dim roar rose from far away in the front of the crowd, undulating its way through the masses until it reached us and we screamed with fervor.

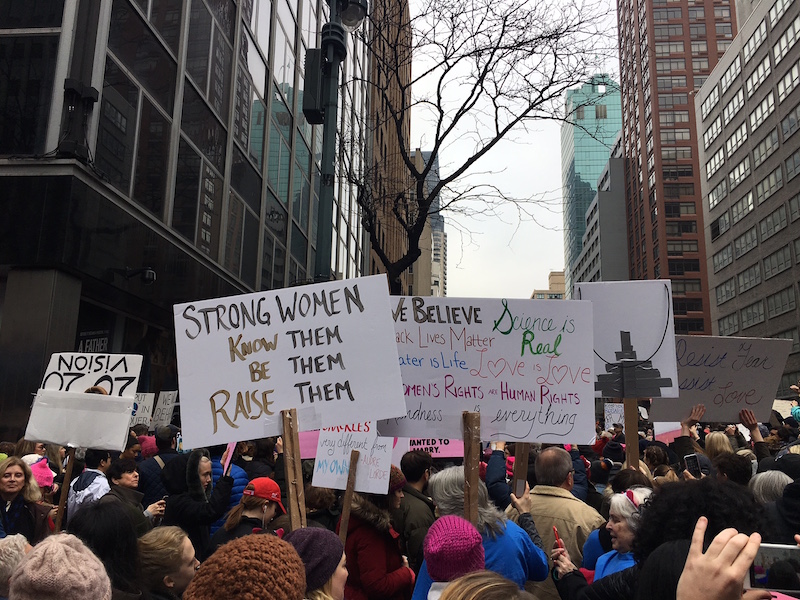

The signs embodied various degrees of creativity and civility. “Post Menopausal Women for Reproductive Rights!” chanted four magnificent women on the far end of 60th. A glittered, neon pink sign read, “Melania, blink twice if you want us to save you!” Two girls in their teens maintained a patient and powerful air of maturity, donning Rosie the Riveter denim shirts with red bandanas knotted around their foreheads, holding her iconic “We Can Do It!” sign.

The night before, as Donald Trump stood in front of hundreds of thousands of Americans and became our 45th president, we hunkered together in our homes, crocheting pink caps and staining our fingertips with Magic Marker ink. We scrawled signs of frustration, of defiance, of comedic protest against Trump’s tiny hands. As Trump stood in front of the world, and claimed to work for us all, swearing allegiance to this country and its people, claiming to never disappoint us, we looked to writers and activists to tell us how to move forward. We searched online for quotes that inspired us, quotes that could quell our mounting anxieties, quotes that could answer why this has happened. I chose a quote from Audre Lorde: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” As I carefully inscribed her words onto a white piece of poster board, I messed up twice. I lace the red and blue ink through the big block letters and post a proud photo to Instagram, explaining why I was protesting.

Friends in D.C. shared photos of packed buses and planes on their way to the rally, videos of women marching side by side with generations of their children and grandchildren. An acquaintance in Serbia marched seas and thousands of miles away. In my hometown of Cincinnati, an ebullient throng of my friends took to the center of the city, winding through the streets I roamed as a child. My mother, a teacher for gifted students in the Bronx, assured me that most of her fifth graders hate our president, though some deeply fear him, convinced that those close to them will be deported. She kept reminding me: Trump works for us. He works for us now.

On that Saturday in New York, surrounded by mostly other white women, I felt frustrated that we weren’t angrier. I found myself glaring at groups of people chatting and laughing. I felt a pang of regret for not going to D.C., the center of it all, where women were marching and chanting at the president in his own backyard. A middle-aged woman in a gray knit cap fumbled over of the police barricades and took to marching on the open side of the street. “Where’s the urgency?” she yelled at no one in particular. A few people around me made tense eye contact but there was no response. “This isn’t just for fun; we need to stay angry!”

The progression was painfully slow. It took 30 minutes to move a block. There were moments of exhilaration when we marched underneath the bridge to Grand Central and sang the lyrics to “I Will Survive.” I finally found someone playing music and joined a woman dancing in a leopard coat. We followed her for 20 minutes, dancing to “Who Run The World?” It was looped on endless repeat.

I tried to keep my spirits up, tried and failed to start my own chant. Eventually I extricated myself from the steady progression and marched down the sidewalk next to them, looking for a more energetic group. At times, the protest felt like a production that many had showed up to with good intentions for the sake of solidarity, to be a part of this critical time in history. But we can’t just choose to be activists only when it’s convenient. One sign warned “the price of apathy is to be ruled by evil men.”

I woke up sickened on November 9th, as so many others did, at the thought of what we had lost. That night, I went to Union Square and joined the throng of furious protesters, drenched by the deluge of rain. The soaked streets were packed with signs defending Muslim rights, LGBTQ rights, and Black Lives Matter. There was no guidance, no organization telling us what to do but we chanted in unison for hours. We surged out of the square and took to the street, trudging uptown, magnetized by the golden glow of Trump Tower. Soggy signs beat on against the wind. We chanted “Not My President,” through raw vocal chords. The energy was pure fire, pulsing fear, consuming anger.

There is a physical and emotional fallout the night you return from a protest. Back at home, falling into bed in torpid stupor, it’s impossible to imagine the way forward. There is no map for the next four years. Away from the thousands of protesters, there is a moment of realization where you wonder what to do next.

In class the week after the election, I sat in a quiet circle of other journalism graduate students. We were downcast, unsure of where we stood. We asked our professors for guidance and hope. There were no easy answers. The role we now inhabit as journalists is critical. We must become those we sought guidance from for the quotes on our posters.

In the days after the protest, as I take in the gravity of the protest photos from around the world, I find hope in Adrienne Rich’s poetry, that filled my social media feeds from the words on posters. “The connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic, and the most potentially transforming force on the planet,” one sign reads. But it is a quote from Rich’s famous poem, “Diving into the Wreck,” that reminds me why we must keep fighting. Rich reminds us that the work we do is arduous, and that for the next four years, we must strap on our armor alone and dive into the wreck:

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.