$338,000 into the story, my credibility is called into question.

After my boyfriend has cheated on me with a woman who calls herself by my name, who shortened the elegant, though admittedly excessive, syllables to Stina, I will board a flight from Boise to Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport to Dublin and fi`nally, inevitably, to Rome. I will pass through customs and find myself newly single in the most romantic city in the world, knowing he had only cheated because my book was reviewed in Ploughshares. My replacement, the girl bearing my name into the cheapest, dirtiest bars in all of Idaho, will make him feel as though he is the rock star he has always known himself to be. When he enters the room, he will hear that sudden intake of breath, her stuttering and dumbfounded awe.

Competition, that darkly feathered bird, had nested in both of our hearts. For months, we practiced the art of competing on each other, watching one another’s movements over the whiteness of our screens. The wish, as we both understood it, was not for visibility in our respective fields, but rather, for confirmation, that someone else had seen the light we had always known was waiting there, inside of each of us. In this way, we learned one another’s fears as our own worst habits were, one by one, revealed.

The last time we talked, my ex-boyfriend was still concerned with his book, its faults and its merits. Will you put in a word for me, he asks, not realizing at all what I knew and had always known. Now it is a contest of silence, which is visible only in the shape of my mouth. He only writes for himself, he insists, and only wants the book publication in order to receive tenure: simple and reasonable goals that will ensure food and health coverage for us both.

I shudder to think of the truth he has let fall into the darkening hole that is his throat. I shudder because I know his manuscript is what reminds him that he is a man, that he cannot tell where the pages end and his own body begins.

¤

When the sorrow becomes too much, the Colosseum looming above a brightening city, I will tell anyone who seems to understand English that I do not believe in love. They will stop and look at me in anticipation of a breakdown. I will simply keep walking, counting each of the marble statues in the Borghese Gallery. I will tell the story to myself, the narrative growing darker and more intricate with each attempt, each repetition, each beginning.

When classes begin at the university’s international campus, I describe my academic discipline as “Sadness Studies.” Later that day, I will slip into a tiny room and fix my hair before the department’s annual party. When I return, I will realize that because I seem vulnerable, a girl made entirely of glass, I have become a magnet for married literature professors. But really, I am more like a lightning rod.

When my academic advisor kissed me, the entire room went white.

¤

More often than not, I am accused of orchestrating the situations in which I am noticed. The next day, I am standing near the refreshments, wondering when the weather will finally, inevitably, break. My dress, of course, is darker than it had been the night before.

It is widely believed that younger girls retain too much, if not egregious amounts of, agency in their interactions with the seemingly infinite men in blazers and corduroys that surround them. Such agency — as possessed by female students, and as imagined by newly minted female professors and the women who provided a seemingly endless supply of contingent labor — was really the only power that they had at all. An adjunct instructor at the University of Toronto told me, in an interview, that she intended to use the men as much as they tried to use her. “You know I’ll play up my sexuality to get that recommendation letter, or a fellowship award. It’s how my female mentors taught me, and it’s how we women survive in a masculine field.” Of course, this brand of feminism has its limits.

When he approached me next, he had a class of wine in his hand, an obvious harbinger of what will happen next.

I literally couldn’t stop thinking about your poem.

Have you been to this museum.

There is a room there you should see.

It has been said that a name contains within it the very thing it signifies. Because I did not, could not, comprehend the language, no matter how slowly he spoke to me, I did not realize the nature of what was being described.

The name would appear again much later, blinking its blue light from my telephone. Needless to say, I did not yet understand.

¤

The next day, I take a train to the museum. I travel alone because he has already been there the day before with his wife. I will walk nine blocks in the rain, searching for building number 78. I stand in line and buy a ticket, which is nine euros, but I remind myself that the exchange rate that day was kind.

Despite my predilection for imaginary landscapes, I had started to recognize the limits of my education, its ability to prepare me for the actual world. But really, the best translation could not have warned me of what I saw, and what I would see, in the lavishly decorated and subtly gilded rooms of the museum.

In the first of the corridors, the heads of various livestock hung from the walls. Hunting trophy after hunting trophy after hunting trophy.

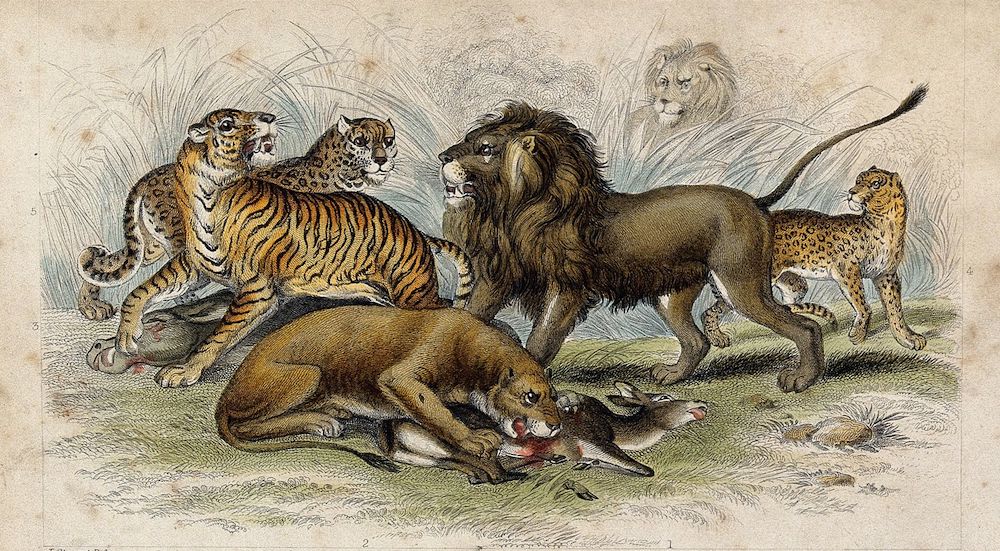

As I pass through the next three rooms, I will be face to face with elaborate taxidermy models of predators hunting their prey. Here a lion, there a bobcat.

Standing there alone and cold, drenched and in debt, I begin to think irony. I begin to think metaphor.

¤

In the months that followed, I would stop returning his messages. I would walk to the grocery store alone, only to look through the window and see him waiting for me in the street. I would use speakerphone when having an honest discussion with him, only to be asked to leave Starbucks when the names he called me verged on what is truly awful. I would finally, and inevitably, be bullied out of accepting a career opportunity that involved another male mentor, as well as health insurance and $20,000 in cash.

But how do you know it was an abuse of power, even my closest friends would ask. How can you be sure that he was the one who crossed the boundary. Even women who professed to be feminists would twist questions into statements. In the months that followed, it was asserted, mostly by other female graduate students, that I was not pretty enough for this narrative to have factual merit. What in the world would he want with you, they insisted, before the conversation shifted to Rebecca Solnit’s latest essay in The New Yorker, or a pithy tweet from Roxane Gay about equality and social justice.

You are always trying to attach yourself to successful men. You have a self-esteem problem and you should get help. Try dating a student, since he would never look at you. When it seemed as though the day could not grow any darker, this lingering disbelief became yet another abuse of power, as I made myself vulnerable by speaking out, and was prompted, time and again, to doubt the reality of my own experience.

Needless to say, I am not the first person to be victimized in such a way and met with skepticism, nor am I the last. There is a tendency to shift blame in these situations, for women to accuse female victims of attention seeking behavior, to pressure them into owning some degree of complicity. Roughly translated: these innumerable abuses of power are internalized, as our culture pits individuals from historically marginalized groups against one another, if only to prevent them from rising up.

Vox Magazine reports that 75% of women who spoke out about sexual harassment in their workplace or academic programs were, at some point, doubted, disbelieved, or otherwise bullied by both men and women who were in power over their careers. For this reason, this EEOC reports that the percentage of women who suffer workplace sexual harassment could be as high as 85% of women who are employed, across disciplines, salaries, and professions. Of course, this is merely an estimate, as the existing atmosphere of fear, shame, and intimidation makes it difficult to even assess the full extent of the problem.

The riddle, as I understood it, was this: which one is worse, the perpetrator or the lawyer who comes to his defense?

¤

What I have not yet said: I am still trying to pay off the $26,000 student loan I incurred for six months of sexual harassment, controlling behavior, and mental abuse, for a time in my life when I doubted every thought, perception, and memory that I held in the locked rooms of my mind.

I am reminded, every time my Mohela statement comes in the mail, that I was not pretty enough to be believed. Needless to day, I will open the envelope. I will pay the bill, noting the account number in the bottom corner of the check, and I will move on.