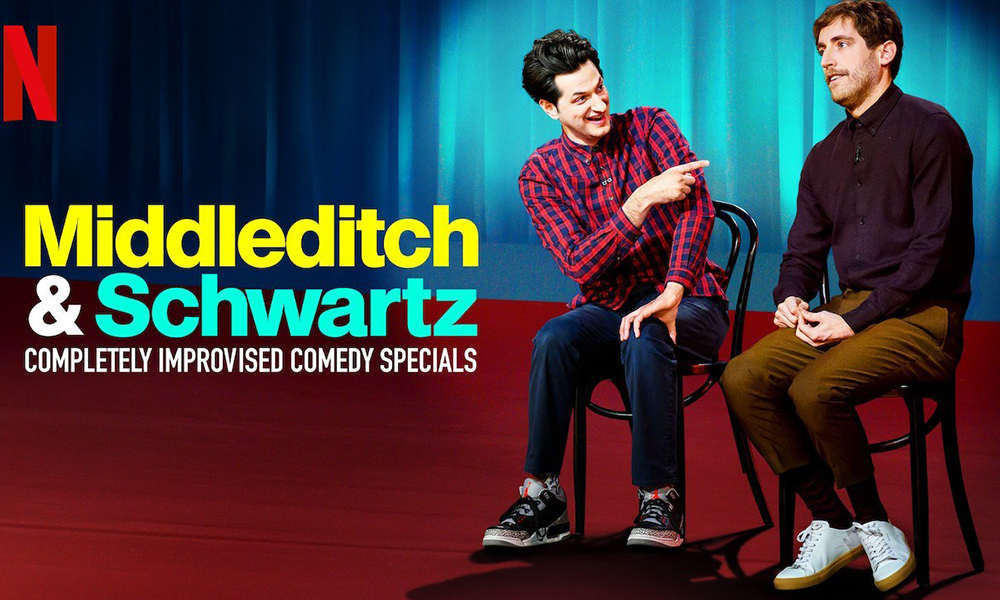

The second episode of Middleditch and Schwartz is about contract law. That makes it sound like an (incredibly dry) police procedural, but the new Netflix series is a set of three improv shows, each filmed live. The contract law episode takes place, appropriately, in a law school classroom. Our cast of characters: Randi, a shy girl; Stanley, a misogynist who is proud of his Maryland roots; Nigel, a Brit; Emily, mother of two boys, named Toby and Roby; and Jason, an alien boy who lives in a closet. There are other characters, too, but I forget their names right now, and it doesn’t really matter. What does matter is that you might now be imagining that Middleditch and Schwartz is made up of an extensive cast — all of the understudies, and the understudies’ understudies, of Broadway’s The Lion King, perhaps. Instead, it’s a cast of two.

Charles Dickens is famous for writing lengthy novels with a vast assemblage of characters — none of them, regrettably, named Randi, Toby, or Roby. To help us keep track of his huge cast of characters, however, Dickens bestows tell-tale particularities on the more “minor” characters whom he fears his readers might be most likely to lose track of and forget.

Dickens employs three principal narrative techniques to distinguish amongst his many characters. First, he graces them with silly or striking names, which “fit” or allude to their personalities or physicalities; second, he furnishes them with physical characteristics or sartorial choices that help them to stand out; and, third, he gives them signature remarks and reiterated catch-phrases by which we can remember them.

Little Dorrit’s Flora Finching has an outrageous name to match her outrageous personality, while Bleak House’s Caddy Jellyby and Prince Turveydrop have odd names which betoken the oddities in their upbringings. (There are some names in Dickens, in fact, that even modern comedians might find too on-the-nose for their purposes, like that of Old Curiosity Shop’s Dick Swiveler.) Great Expectations’ Miss Havisham is consistently depicted in her decaying wedding costume, of which she’s managed to retain only one shoe. (The other shoe remains on her dresser while Miss Havisham moons about her deferred-maintenance mansion — hopping, one must assume — in her moldy, decades-old wedding dress.) David Copperfield’s Rosa Dartle has striking facial scarring that not only makes her memorable to Dickens’ readers, but also serves as a constant reminder to Rosa herself of the toxicity of her relationship with Steerforth, another relatively minor character in Copperfield. Dickens defines that same novel’s Mrs. Micawber by her repeated insistence that she “will never desert” her scofflaw husband, while Bleak House’s Mr. Bagnet is known for his incessant verbal reminders, to all and sundry, that “Discipline must be maintained!”

Thomas Middleditch and Ben Schwartz, the two improvisors who make up the multi-character cast of Middleditch and Schwartz, seek to adhere to a similar set of mnemonic devices in their three televised improvisations. As this is improv, however, the two performers incorporate such mnemonics as reminders not merely for their audience, but also for themselves. During the first of those three performances, “Parking Lot Wedding,” Middleditch and Schwartz’s failure to clearly delineate and identify, up front, each of their instantaneously ginned-up characters gives the impression that their entire performance is teetering on the edge of hilarious self-destruction: a fate the possibility of which is inherent in any improvisation.

In this first episode, Middleditch and Schwartz have invented, and each plays, 14 characters. (I counted.) Twenty minutes in, Schwartz is already becoming slightly undone. He indulges in a moment of meta-commentary, floundering to stay in character as he exclaims, “we’ve got a lot of people hanging out here today!” This near-shattering of the fourth wall by Schwartz comes on the heels of an appellation-related misunderstanding. “I’m Amber,” Schwartz has just leaned in to say. “Are you?!?” Middleditch asks. (Middleditch’s character in this scene is named Short Paul, but we’ll get to that in a moment.) Earlier on, the improvisers had already established the name of Schwartz’s character, but now neither of them can remember it. After mulling it over, they agree that Amber’s name is probably Lisa, but also agree to allow Amber as Lisa’s nickname.

But just as they’re about to launch back into the scene, Middleditch stops them again: “Hold on. We’ve got to figure this out.” Schwartz tries to guide them back: “I don’t think there’s much to figure out?” “No?!” Middleditch snorts, stifling a giggle, “Because then I don’t know if I know my girlfriend’s name.” After more back and forth, they unravel their puzzle: Lisa was the name already established for Short Paul’s girlfriend, while Schwartz’s character is named Marnie.

So what almost went awry? What’s in a name? What causes the confusion is that both the name and the character traits of “Marnie” aren’t distinct enough from those of “Lisa.” Middleditch and Schwartz haven’t made the same mistake with Short Paul’s name, though — that’s one they have no trouble remembering, in the same way you might never forget the name Dick Swiveler after reading this article. And, just as Middleditch and Schwartz bumble with names, so does Dickens: Dickens seems to have briefly misplaced the aforementioned Mr. Bagnet’s name in his memory. Throughout most of Bleak House, he is referred to as Mr. Matthew Bagnet, but twice Dickens slips, and dubs him Joseph, instead. His first name is clearly less memorable than his catchphrase, to both author and audience alike.

Short Paul is indeed small in stature, and Middleditch, who first plays him, makes sure that we remember Paul’s diminutiveness by pulling his knees up and swinging his legs about an inch off the ground when he sits down — like he’s in a high chair. When he goes to put out his cigarette, Short Paul has to make a brave leap off, and then an exaggerated hop back onto, that same chair. Marnie, observing with sympathy Short Paul’s struggle to dispose of his cigarette, asks, “Do you want me to stomp it?” Later on in the episode, Short Paul interrupts the wedding: he’s been in love with the bride since the 6th grade. As expected, all 14 characters depicted in the episode are in attendance at the wedding. Middleditch and Schwartz pull out every trick in the improv book to distinctly represent all 14 of them.

Short Paul is the easiest to distinguish: all the other characters stand on chairs since logically they must, given their respective heights, talk down to him. This differentiation is the key to the scene, because Middleditch and Schwartz don’t divvy up the characters: they both spend time playing each. That means that the distinguishing attributes of each character have to be even more distinct, because Middleditch’s rendition of a certain character inevitably will be a bit different from Schwartz’s, and vice versa. Thus Paul stands out because of the chair gimmick, even as — or rather, because — the other characters tower over him.

Those other characters have gimmicks of their own. The duo establish early on that the mother of the bride is a drunk, so it’s easy to recognize “Mom” when one of them slips into her character. Also in the mix at this wacky wedding party are some “friends from music festivals,” who are readily recognizable because they’re always playing their instruments with frenetic single-mindedness. The tightly-wound father of the groom is instructed early-on by his wife to “just loosen up a bit.” As he gets more and more riled up, he consistently returns to his catch-phrase: “I’m LOOSE!”

So, Middleditch and Schwartz utilize all three Dickensian tricks to create memorable characters in this episode: they 1) give Short Paul a striking and silly name, that suits his physical demeanor; 2) consistently make choices that exacerbate Paul’s diminutiveness, to make sure he stands out; and 3) give the father of the groom his own catchphrase, in the same vein as “I will never desert Mr. Micawber!” In fact, Short Paul, like Mr. Bagnet, also has a signature catchphrase: embittered by the loss of his 6th grade crush, Paul is determined to “say something mean” during the ceremony. The officiant makes sure to stop during the course of the wedding to ask, “does anyone have anything mean to say?” “Parking Lot Wedding” also features a ghost come to reveal the truth about the past, which — although not exemplary of any of my three mnemonic “elements” — is nonetheless distinctly Dickensian. The ghost happens also to be the scene’s wedding officiant; so we can call him the Ghost of Weddings Present.

That Dickens took special pains to ensure that all of his characters were memorable is scarcely news. Dickens wrote his works in serialized form, with a new installment coming out every week. Dickens, then, might be said to have performed — and published — textual improvisations on a weekly basis. This incremental unspooling of Dicken’s novels also meant that his readers were all the more likely to forget characters, particularly if they cropped up early on in the serialization, but then didn’t appear again until many installments later. E.M. Forster theorized that “Dickens’ people are nearly all flat,” meaning that they don’t have much psychological complexity. This flatness aids in a character’s memorability: if a character is simple, rather than complex — flat, rather than round — then we don’t have to learn much about them, which makes their one or two distinguishing features all the more memorable (Aspects of the Novel, 71). Andrew Elfenbein likewise argues for the memorability of Dickens characters in his study of reading and memory, The Gist of Reading. He notes that while most of what we remember about novels are characters or events, especially “unpleasant or odd” ones, “with Dickens there is the addition of memory for what characters say” (162).

The free play of the imagination is inherent in any form of original, creative storytelling. This may help explain why it makes sense that, though separated by roughly 150 years, Dickens’ novels and Middleditch and Schwartz’s improv special share some common artistic processes. According to John Hodgson and Ernest Richards, in their 1967 Improvisation, the oral storytelling practice — a kind of improvisation in itself — was a likely point of origination for early Greek and Roman narratives such as The Iliad and The Aeneid. The Victorian novel follows in that same tradition: the serialized form that compelled Dickens to render his characters as memorable as possible also allowed the Victorian novel to, at times, function as a kind of written improvisation. Coming out in weekly or monthly installments, these 19th century works-in-progress allowed room for plot improvisation in the same way that an improv scene does. Indeed, many Victorian authors wrote their serialized novels without a clear plan, or at least with an open mind to potential changes. William Makepeace Thackeray adroitly altered the plot of his most famous novel, Vanity Fair, when readers failed to respond positively to his early installments. Similarly, Dickens confessed that he wrote his serialized novels without a fixed, inalterable end in view. He dismissed the risk that his still-in-serialization Oliver Twist might be purloined for unauthorized theatrical adaptations, noting that “nobody can have heard what I mean to do with the characters in the end [of Oliver Twist], inasmuch as at present I don’t quite know myself” (Rosenthal, Good Form, 54).

Most histories of improv comedy mention Commedia dell’arte before leaping forward 300 years to Keith Johnstone’s TheatreSports (a form of competitive improvisational comedy which became the inspiration for the television series Whose Line Is It Anyway?), and to the formation of improv theaters like UCB (the Upright Citizens Brigade), which launched the careers of Amy Poehler, Donald Glover, and Ben Schwartz. This leap in time seems not negligent, but necessary to historical accuracy: we have no evidence, for example, that Dickens witnessed improvisational comedy, in any form akin to 21st century improv, on the Victorian stage.

Dickens was, however, a fan and part-time practitioner of the theatrical arts. At 20, he auditioned (unsuccessfully) to act upon the stage of the Covent Garden Theater. In mid-life, he co-authored two plays with fellow novelist Wilkie Collins, and was well known for his reading tours, during which he took on the personas of his characters with flair. During the final 13 years of his life, Dickens engaged in an extended affair with the London actress Ellen Ternan.

Yet Dickens seems also to have had a fraught relationship with the theater. James Eli Adams argues that Dickens was uncomfortable with theatricality, enough so that his quandaries about the art form came through implicitly in his work, in the form of “representations of disrupted or failed theatricality, which are bound up with the experience of shame” (Adams, Essays in Honor of J. Hillis Miller, 318). Part of this discomfort is born out of what J. Hillis Miller, talking about Dickens’ early work, Sketches by Boz, calls “inauthentic repetition” (Miller, Victorian Subjects, 140).

In this sense, improv comedy is the opposite of theater. Improv comedy is authentic, in that improvisers do not know what they’re going to say next until after they’ve already said it. And improv comedy is not repetitious: no two improv shows are the same. In fact, The UCB Comedy Improvisation Manual stresses the importance of the “organic scene,” during which “the first unusual or interesting thing” — the moment around which the improvised scene will be formulated — “will be found during the course of the scene” (70). It is not so very difficult, then, to imagine a (time-traveling) Dickens in high spirits, chortling away in Row A of Middleditch and Schwartz, and not for one second regretting the lack of inauthenticity and repetitiveness that he negatively associated with scripted theater.