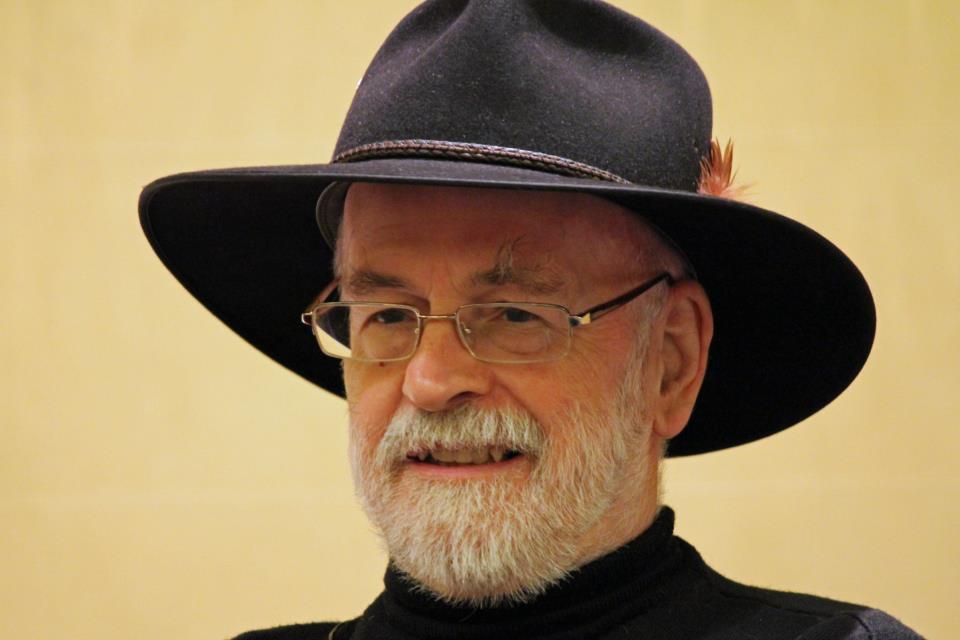

By now, of course, Death is almost an old friend. You’ll know him when you see him—tall chap, skeletal, scythe, black cape, a BOOMING VOICE, rides a pale horse called Binky… and he’s a recurring character in virtually all of the Discworld novels written by Sir Terry Pratchett, who has died at home on March 12 2015 from a chest infection caused by early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. In an early volume, Mort (1987), Death moves from cameo to secondary lead, perhaps even antagonist, as he takes young Mort on as an apprentice. Whilst Mort struggles to carry on the work, Death finds work as a short order cook in a tavern and begins to get to know living people. The novel echoes earlier works featuring Death—Alberto Casella’s play Death Takes a Holiday (1924) and the films The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957) and Love and Death (Woody Allen, 1975)—but it is not just a parody: it explores the nature of work. A few books later, in Reaper Man (1991), Death is made redundant and seeks work on a farm as an odd-job man, only to find his traditional scything skills are threatened by threshing machines. The novel is a comedy, but it is also about stuff.

It should not be a surprise, then, that Pratchett’s Twitter feed announced his demise by means of an imagined meeting with Death: “‘AT LAST, SIR TERRY, WE MUST WALK TOGETHER,’ it said.” The two walk off together on to the black desert under the endless night. Nor should it be a surprise that a petition then appeared on “change.org” demanding that Death bring Pratchett back. But that is a sentiment that Pratchett would first laugh at and then refute. Aware of his failing abilities after his diagnosis, he campaigned both to raise money for a cure for Alzheimer’s and for the right to die at a time of his choosing. As it is, he died in his sleep, surrounded by family and his cat. That latter detail is telling. In Sourcery (1988), the wizard Ipslore the Red asks Death what makes life worth living. Death thinks for a while and answers, CATS ARE NICE.

Terence David John Pratchett was born on April 28 1948 in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England, a town between High Wycombe and Gerrards Cross. At school, he was put into a class for pupils not expected to pass the Eleven Plus, the examination that allowed entry into grammar schools rather into than the more practical, less academic, Secondary Moderns. However, a gift of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and a ticket for Beaconsfield County Library sparked a life-long love of reading. Despite passing the exam, he decided to go to High Wycombe Technical School, where he discovered science fiction. He began writing and his story “The Hades Business” was first published in the school magazine and then in Science Fantasy 60 (August 1963). Pratchett bought a typewriter with his payment and his mother paid for touch typing lessons.

Pratchett became part of the British sf fandom, attended conventions, contributed to fanzines, and sold a second story, “Night Dweller,” to New Worlds 156 (November 1965). Pratchett gained five GCE “O” Levels and started studying for “A” Levels in Art, English and History only to drop out to work for the Bucks Free Press. Whilst filing stories on weddings and parish council meetings – and a weekly serial for children – he planned a number of novels.

One assignment was to interview an author about a forthcoming book published by Colin Smythe Ltd, based in Gerrards Cross. Pratchett mentioned to Smythe that he was writing a fantasy novel about a civilization living in a carpet, The Carpet People (1971), and the company agreed to publish it. The book did not sell well, although they still produced his second novel, The Dark Side of the Sun (1976). This was sf, in part a parody of the alien artifacts discovered in Larry Niven’s Ringworld (1970), but also of the psychohistory central to Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy (1942–1951).

In 1980, Pratchett left journalism to work as a publicity officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board. He wrote a third novel, Strata (1981), in his spare time and this was partially set on a disc-shaped planet. This was again a parody, in part, of Niven, but some was not yet quite right. When he switched genres to fantasy, this gave him a perfect stage for a series of comic adventures that would send up the conventions of fantasy: a flat world balanced on the backs of elephants stood on a turtle swimming through space. He imagined an inept wizard, Rincewind—Gandalf’s opposite—acting as a tourist guide for a naïve tourist. Smythe published The Colour of Magic (1983) and was able to interest Corgi in a paperback edition; they sold the radio adaptation rights to BBC Radio 4. The book became a bestseller and a sequel, The Light Fantastic (1986), followed. The sales became too much for Colin Smythe Ltd to manage and so Gollancz became Pratchett’s publisher, Smythe became his agent, and he became a full-time novelist. The copies printed increased with each new title.

Pratchett wrote a number of Discworld Bildungsromans: Equal Rites (1987), about a female wizard; Mort; and Sourcery (1988) about Coin who might grow up to be a powerful wizard. There was already the sense that Pratchett was commenting on the real world alongside his reworkings of Tolkien, Howard, Lovecraft, and others. However, in order to continue the sequence, he would have to cast his net wider than one genre. Wyrd Sisters (1988) mixed Shakespeare and silent comedy into its fantasy about a coven of witches. Pyramids (1989) could have as easily been a comedy set in Egypt as a Discworld novel, a fantasy cousin to Carry On Cleo (Gerald Thomas, 1964). Indeed, the series owes something to the rather bawdier film series: a familiar ensemble of comic actors or types, interacting in a series of locations. Whilst the Carry On films took hospitals, the army, the western, the reign of Henry the Eighth, and the horror film for its jumping off points, Pratchett took versions of Australia, China, Hollywood, the police procedural novel, rock music, opera, journalism, telegraphy and banking for his. The books were rich with the tiny details of knowledge and allusion that Pratchett had gleaned over the years. At the time of writing, there are forty Discworld novels, with an apparently final one in the pipeline. Only J.K. Rowling outsells Pratchett in Britain. There are Discworld novels for children and young adults, a picture book, a cookbook, tourist guides, maps, diaries, games, companion guides, graphic novel adaptations, and other merchandizing. There are four Discworld science books, co-written with Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart.

Away from the Discworld series, he produced the Bromeliad trilogy (1989–1990), the Johnny Maxwell trilogy (1992–1996), Nation (2008), Dodger (2012) and Dragons at Crumbling Castle (2014) for children. He co-wrote The Unadulterated Cat with cartoonist Gray Jolliffe (1989), Good Omens (1990) with Neil Gaiman, and The Long Earth (2012), The Long War (2013) and The Long Mars (2014) with British sf writer Stephen Baxter.

While each new Pratchett book becomes a bestseller, the literary establishment has been less generous. There is a lazy assumption—most recently characterized by an episode of BBC Radio 4’s A Good Read, in which veteran journalist Katherine Whitehorn’s “surprise choice” of reading recommendation was The Colour of Magic. The program’s webpage asks, “if three adult women [will] agree on a novel from a series usually thought of as the preserve of teenage boys.” They do—and positively—against their better judgment. Pratchett’s background in fantasy counts against him—Tolkien, after all, is still patronized—and it is assumed that comic novels cannot also be serious. Alongside Pratchett’s humor and humanity, there are condemnations of sexism, racism, xenophobia, and the misuse of power. The constant centrality of Death draws attention to a bleakness within his ethical vision. People die. There can be no bargaining.

We are left with memories of his many appearances at conventions, the legendary queues for his autograph, his accumulated wisdom, and shelves full of books that will be read by people of all ages—male and female—for the foreseeable future.

Andrew M. Butler is the author of the Pocket Essential Terry Pratchett (2001), editor of An Unofficial Companion to the Novels of Terry Pratchett (2007) and co-editor with Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn of Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature (2000, 2004).