By Kyle Proehl

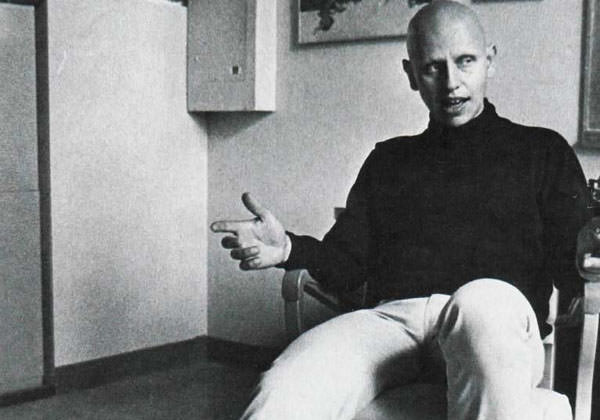

David Antin, who moved to San Diego from New York in the 60s and began composing the talk poems for which he became known, died last October.

In one of these poems, given for Kathy Acker in 2002, he talks about the move. It was 1968, and on the drive across the country, the night before arriving in Solana Beach, he and his wife Eleanor heard that Robert Kennedy had been shot. Coming from New York, where where they had been active in protests against the Vietnam War, despite being told San Diego was “a bunch of scientists with an open checkbook under a palm tree,” they expected to find people responding to the killing.

What they found was a used junk store, where they had gone to buy a refrigerator, full of photos of Adolf Hitler “taken up close by people who must have known him.” Outside the store two elderly gentlemen were discussing Kennedy, and one said to the other, “he deserved what he got.”

This kind of moment, and the attempt to tell it, marked for Antin the distinction between story and narrative. For Antin a story was a configuration of events or parts of events that give shape to some kind of change. Narrative was a psychic function, where a subject desiring something is confronted with a potential transformation.

The talk poems performed the difference, were narrative in action. By attempting to shape his thinking out loud before an audience, Antin brought himself toward a familiar crisis that might become an intimate experience for those who were present. That experience only became possible through improvisation.

The trend toward improvisation has taken on a new prominence in the national political theater. The man elected president had a memoir written for him in the eighties, The Art of the Deal, that begins with the boast that he never brings a briefcase to work. Knowledge is dead weight, like furniture. This has proven to be a popular stance, but the limitations lead easily to defensive vulgarity.

In the real estate mogul’s memoir you can find statements like “unfortunately, rent control is a disaster for all but the privileged minority who are protected by it.” This familiar reversal marks a failure to confront the change suggested by a discomforting set of terms, and makes a claim on meaning violently, as though it were a possession. But probably the most stunning incapacity for experience and contemplation comes when confronting, or eliding, the death of his older brother, who instead of adopting the family business took to flying planes and drinking. Barely two pages on their entire relationship ends with the summation: “At the age of 43, he died.” We know little brother doesn’t drink, but rather than pause for even a moment above the potential abyss, he slides right back to the action. From such avoidance one sees how assuming the spotlight of power can be an expression of cowardice.

Antin preferred the fringe. Not the myth of Odysseus, he said, but Odysseus as he myths; not the tale of a king who returned to his throne, but a man telling stories that might help him discover the way and the meaning of home. In his piece called “The Fringe,” he talks about dodging the spotlight, not through some determined plan, but by spontaneously refusing to become the property of a reporter’s promotional story.

When the focus is not on power but on what power cannot grasp, talking about the duration of art objects might lead to telling how his mother cannot remember he has just given her a box of chocolates. Or talking about the meaning of the avant-garde becomes a way of dismissing tradition, which is just art as inherited property, in favor of a capacity to confront unexpected death. And not death in the abstract, but a distant uncle’s accident at a moment when they’d been brought somewhat close.

I lived in San Diego a number of years, but only saw Antin perform after moving to New York. In Talking, from 1972, you can see the shift across the book from the documentary aphorisms of “The November Exercises” to “Talking at Pomona,” which looks and reads in the mode of everything that would come after. Just before “Pomona,” both in the book and in the generative sense, is “The London March,” a transcription of a conversation with his wife Eleanor. They are playing cards for a war protest set to happen in London, playing the game like it might do some good, and wondering about being far from friends, wondering where they are now.

When I saw David in 2013, he and Eleanor, who is a visual artist and writer as well, appeared together. She read first, from her Conversations with Stalin. Then David talked, mostly about dreams and their relation to language and story. He spoke about a dream he had told to a therapist who was helping him deal with Parkinson’s. He kept pulling tissues from his pockets to wipe his nose, then returning them to the seam of pocket where they would rest briefly before falling to the floor. In his dream he saw what was consistent from his earliest poems through the latest; namely, the impossible desire to stop the imperial mission of the destroyer, America. Impossible because stopping it would almost certainly mean its destruction.

At the end, they took the stage together and performed a delightful misunderstanding of the dull questions thrown up by the most eager in the crowd to be heard. It was like being in the kitchen with someone’s grandparents, yet what they offered was not merely evidence of an enduring relationship, it was the renewed and exposed spontaneity of love. I remember the strange impatience of one guy, maybe embarrassed by his own contribution, who wanted to know if they shared methods. Being forced to repeat his question led to a brusque, “Writing or talking?” to which Eleanor brilliantly replied, “We talk all the time.”