A society’s cultural evolution is determined by its persistence in questioning its own moral system. Dark Progressivism: The Built Environment, a recent exhibit at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History, continues this social discourse through revolutionary artworks that challenge our vision of virtue by representing a culture that has persevered in the periphery of the American Dream.

Street gang culture is a way to deal with the social paradox of existing in a world where the “American Dream” seems impossible to young working-class, minority adolescents who cannot match up to their white counterparts, but have a value system different from their immigrant parents.

These words introduce Urban Politics: The Political Culture of Sur 13 Gangs by Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre, who conceived of “Dark Progressivism” as a Southern California art movement. As a former member of a Los Angeles street gang, and with a degree in Political Science and a Masters degree in Creative Writing, d’Ebre uses the language of formal political theory to systematically analyze the political and social structures of street gangs in Los Angeles. This insider’s perspective provides a necessary addition to the discussion of the various social issues faced by low-income communities. It is through the arts that members of these communities, such as d’Ebre, Leafar Seyer, KRS-One, or Ice Cube, have created a platform to educate both mass audiences and scholars about the realities of those communities beyond what is represented in the news media, taught in school curriculum, or addressed by law enforcement.

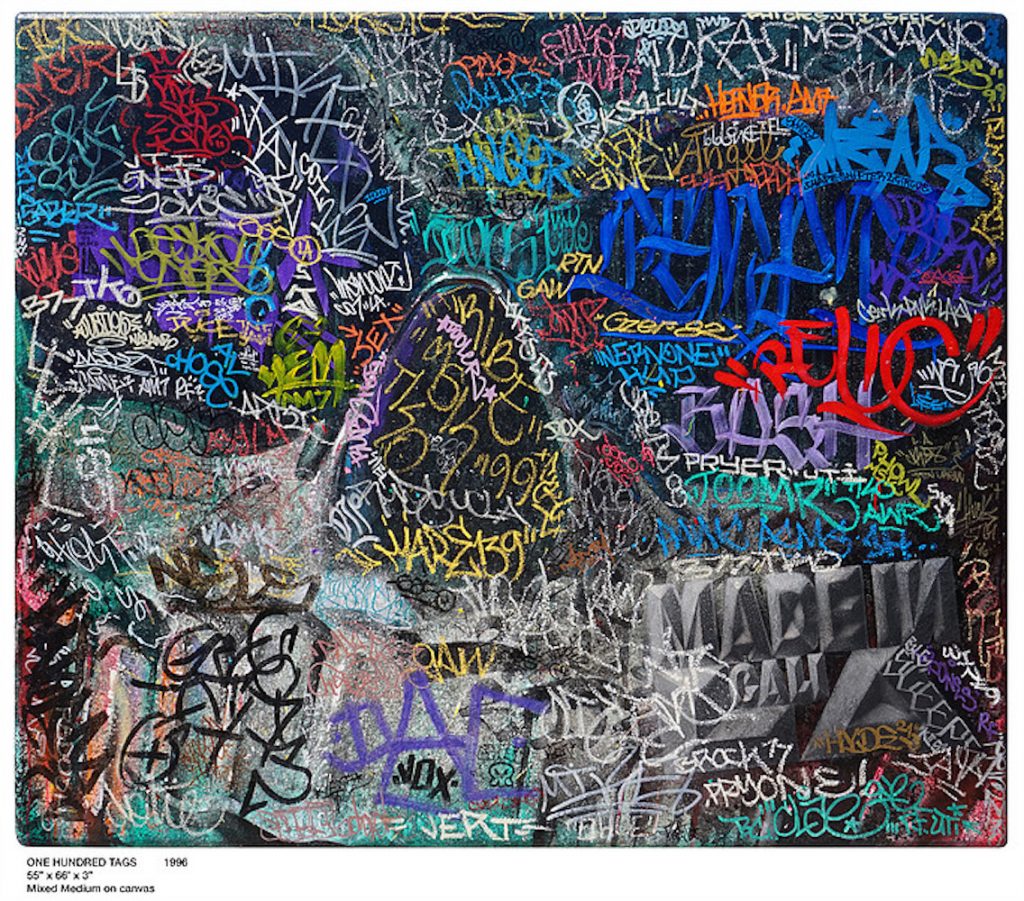

D’Ebre writes in Urban Politics, “Urban artwork alters and trains perception like any other art movement, but forces the populace to look at their artwork through a lens of realism and despair, rather than judge it as a consumer commodity or as trained professional art historians or critics.”

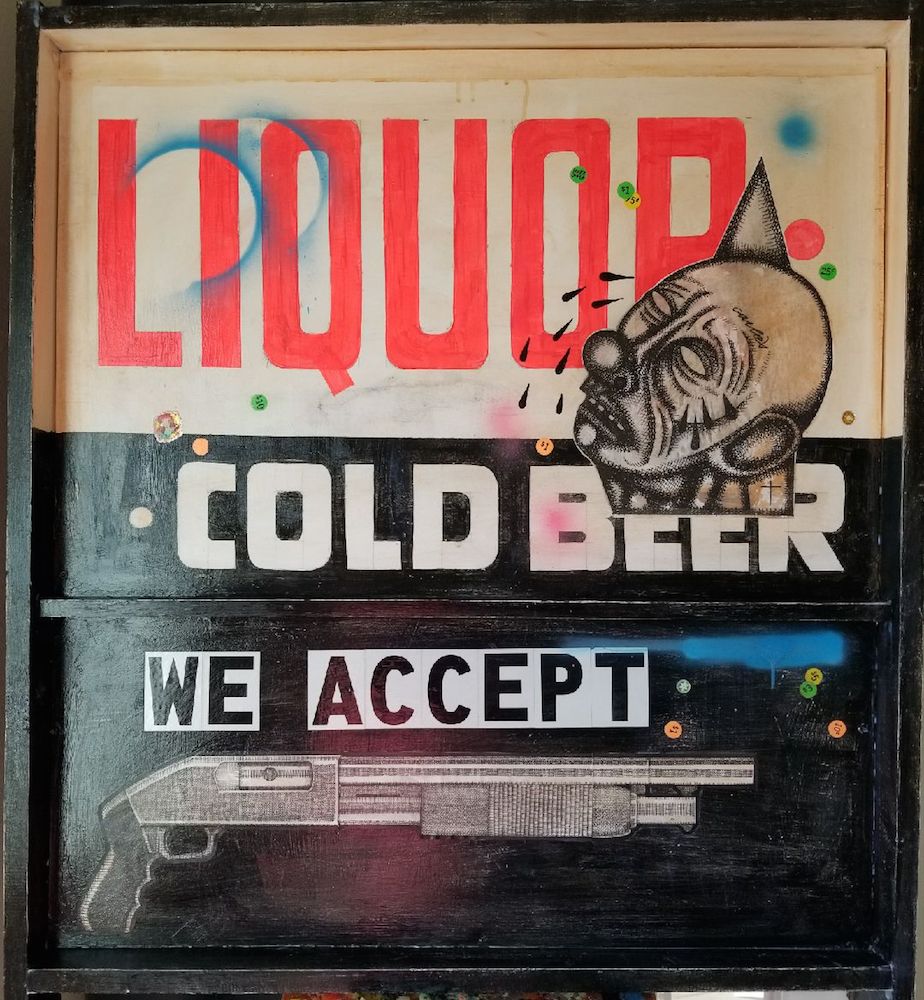

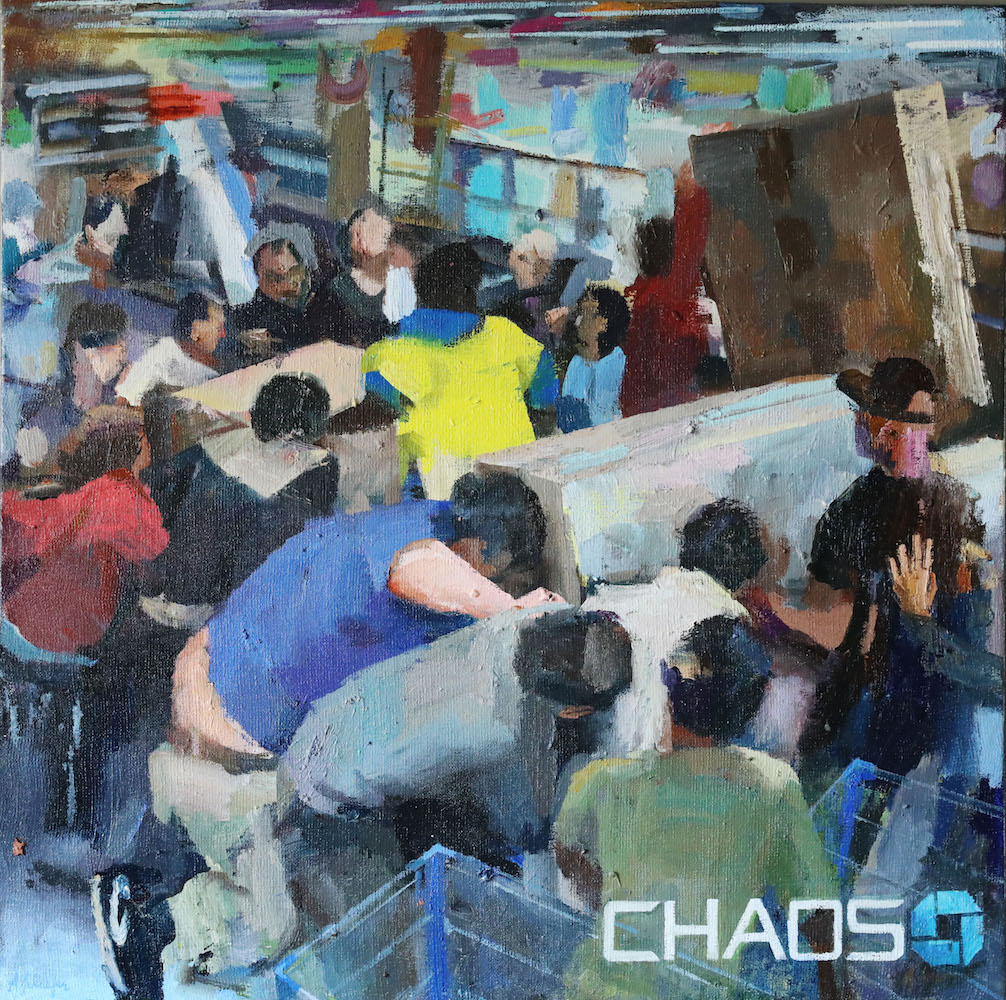

Like hip-hop, urban artwork, which includes graffiti, tattooing, photography, painting, drawing, and sculpture, goes against the conventions of the commercial art world, while serving as social and political commentary. But many audiences, scholars, and professionals have overlooked these values, due to the unconventional and provocative manner in which the artists work and communicate. D’Ebre writes, “Street gang members cannot meet the demands of the general population or the typical technologies, thus they become non-conformists and seemingly irrational to the homogenized linear thinker.” This is where messages get lost in translation. The “irrational” is a misconception. As d’Ebre makes clear in Urban Politics, there is order in the chaos.

I’ve heard similar sentiments in critiques of rap music, which often go something like this: “It’s just senseless noise that glorifies violence and crime.” Or, I hear, “I don’t have a problem with rap, it’s just that I can’t relate to that culture.” My response to those statements goes something like this: “Rap is punk.” Some say punk music died in the ‘80s, but at its essence, rap music was and still is punk. The punk movement was characterized by its anti-establishment, anti-authority, and non-conformist views. N.W.A.’s 1998 song “Fuck Tha Police” sharpened the edge of the punk spirit where punk rock went dull. You don’t have to identify with black culture or be black to comprehend and appreciate the culture and political messages delivered in rap music. It was through rap music that many Americans learned about the harsh realities of Los Angeles, the Bronx, and many other low-income neighborhoods in the throes of urban decay. Understanding this environment is crucial to comprehending the rationality within the art. Dark Progressivism: The Built Environment addresses just that — the environment.

When we talk about race and racism as social constructs, we need to explore how these constructs were designed, and who the architects were. American ghettos are not a social phenomenon that manifested by accident, but rather the result of deliberate design. Urbanization rapidly changed the residential topography in America during the early 1900s when people moved from rural farmlands into cosmopolitan cities. The Great Depression that followed World War I led to a lack of housing development that characterized major cities until the Second World War. It was during this time that a second Great Migration of African Americans relocated from southern states to northern and western ones in search of economic opportunities in the war industry, and to escape racism in the south. But in many of those states, including California, African Americans were still treated as second-class citizens. White residents settled in dreamy suburban neighborhoods that were fortified by restrictive housing covenants that legally permitted real estate agents the right to deny selling to non-white buyers. These restrictive covenants channeled minorities into housing projects, many of which still exist today.

In Urban Politics, d’Ebre explains that Los Angeles has approximately 88 incorporated cities, but not all have an official city seal or a chamber of commerce. There is an additional 40 unincorporated cities and 47 unincorporated communities without a city hall or a chamber of commerce. Generally, within these unincorporated communities there is a lack in social services, overpopulation, and lack of economic opportunity. As a result, street gangs formed to create their own constitution, to provide economic opportunities, and to govern their own neighborhoods. Within these communities, some people have advanced their economic opportunities through art. This is where Urban Politics ends and Dark Progressivism begins.

“I’m a gangster, not a criminal.”

Leafar Seyer said this to me at the Dark Progressivism: Metropolis Rising booth at the 2015 LA Art Show. Seyer is an former gang member; he’s also an activist, a visual artist, and the singer in the Cholo-Goth band, Prayers. I felt ashamed, and enlightened, for realizing that I had never disassociated those terms. Previous to my conversation with Seyer, I was informed by d’Ebre of struggles he and other Dark Progressivism artists have faced in trying to engage with art institutions. In 2014, Galo Canote curated a graffiti art show Con Safos (With Respect): The Art and Culture of Urban Chirography at Muzeo, in Anaheim. Unfortunately, the Muzeo board of directors had second thoughts when some board members complained, and even went to such measures as to bring the Anaheim Police Department’s gang division into board meetings to observe the artworks. Muzeo cancelled its graffiti art show. Three years later, however, after the Dark Progressivism documentary made its rounds in the film festival circuit, the Lancaster Museum of Art and History welcomed d’Ebre, along with co-curator, Lisa Derrick, to host Dark Progressivism: The Built Environment, which closed January 14, 2018.

Hip-hop, street, graffiti, and tattoo art, once taboo in society and in the art world, is now widely accepted and celebrated. Despite this assimilation, the communities from where these arts originated are still on the margins of society. I felt this paradox was artistically rendered during last year’s LA Art Show, where a section of the floor was reserved for street artists to paint murals on a fabricated wall during the show. One artist painted a tombstone, upon which read, “RIP street art. Died from exposure.” This statement, either about an underground movement dissolving upon exposure to the mainstream or a trend losing momentum due to oversaturation in the commercial art market, does hold some truth in that context, but also neglects the communities where street art originated and remains very much alive. Street art in Southland goes back to those post-war housing projects when youth began writing on the walls and carving their names in the cement. Eventually they would carve their skin with tattoos and tag the walls with graffiti. For artists of Dark Progressivism, street art is not a commercial trend meant to be viewed “as a consumer commodity,” but a unique part of their culture that still thrives. D’Ebre explains:

Our styles of lettering, our Southern Cali-look, our tattoo culture and laidback vernacular have spread around the world. And now our art, which exposes the darker elements of Los Angeles and its past, while emphasizing a forward movement, has gained momentum, both in its homeland and globally.

What we don’t want to see are the origins of street and tattoo art dissolve as it assimilates into mainstream culture. Nor do we want to see the doors close on artists when the trend of those appropriating the style fades. What these artists have to offer is something that cannot be fully imitated. Presenting Dark Progressivism at MOAH has helped preserve the history of this culture. As cultures have done for millennia, history and tradition is passed down through the arts and storytelling. Dark Progressivism follows this model with “Payphone,” an installation by Jose “Prime” Reza, with an accompanying short story by d’Ebre, which gives the audience a lens into the payphone culture of the ‘80s and ‘90s. During this time, gang violence and business was conducted in the streets. Payphones were especially high-risk because they face away from traffic, and callers could not remain fully aware of their surroundings. As a result, as Reza’s piece recounts, many gangsters have been killed at the payphone. It is this eyewitness transmitted through art that weaves a thread into the greater cultural tapestry of the Southland. And it is the artists and members of these communities that are the weavers.

The rapper KRS-One made a point in a lecture about hip-hop that is relevant to the conversation about the Dark Progressivism movement. He explained:

What makes you a hip-hop scholar? Some subjects you can study objectively. You can look at something, observe it, and then form a hypotheses based on your observations. But cultural knowledge is never objective. You can’t look at a culture and say, “I know what it is.” Or to be more accurate. You can’t eat a slice of pizza and then say, “I’m an expert on Italian culture.” Or most people say, “We’ll, because I had a plate of spaghetti and meatballs I can tell you about Italy.” This is what is happening with hip-hop — this is what happened with scholarship, period. But this is what’s been happening with hip-hop’s particular scholarship. People who are not the culture are teaching you the culture.

As an audience member who is not from Seyer’s gang culture, or KRS-One’s hip-hop culture, I can write about the culture, but my words will never be woven into that cultural tapestry. I can stand with, but I can’t stand within. I can support it, learn from it, appreciate it, share it, and celebrate it. Dark Progressivism as a movement creates spaces in which the audience outside the culture can literally stand with the culture by standing before the art and taking in the messages the artists are delivering. For those who perceive these communities as threatening, standing with this art might be challenging; but this is all the more reason for art institutions to facilitate platforms that promote dialogs between two communities.

Yesterday’s evil villain might very well be tomorrow’s hero. I can’t help but to think of how this social phenomenon has happened in other areas of society throughout history. Joan of Arc or Teresa of Ávila were both persecuted by their own church, and then were later canonized as saints. Impressionist art was once decried by art critics, but those works are now auctioned for millions of dollars. I’m not trying to canonize, but it seems that reformation and revolution are the keys to maintaining a system that would otherwise remain stagnant. The art world thrives on the drama of revolution. Dark Progressivism is reforming the language and the very conversation scholars are having with street art, and art in general, for that matter. The darkness from where these artists came is what empowers them to deconstruct the 20th century system and build the 21st century experience. If there is evidence for Dark Progressivism achieving this success in leading the conversation in a new direction, one only has to read the writing on the wall; because that writing is now in a museum.