Walter Benjamin famously asserted that “[t]here is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” For Benjamin, a record of history cannot be anything other than a ledger of power, its misuses, and the inevitable shifts of agency, visibility, and influence. The supposed revolutions that we witness, then, are nothing more than reversals or redistributions of what has always been, and what might always be, an unequal share of power in a given cultural space.

In true Benjaminian fashion, Twitter has become the document of civilization in the digital age, the primary forum for politics, activism, righteous indignation, and in large part, the voices of those who feel denied or oppressed by society in some way. With the rise of the #metoo movement, we have seen the potential for power to be reclaimed by historically marginalized groups of people, women foremost among them. The magnitude and duration this movement has achieved is enough to strike fear into the heart of any man.

Indeed, many careers have rightfully ended as a result of social media activism, the recent forced retirement of a tenured professor in British Columbia being merely one example. These allegations of sexual misconduct, like many, would and did hold up in a formal judiciary setting. Yet some accusations we’ve seen on social media in recent years could not survive scrutiny in such a way. In the case of X (real name concealed), the former editor of a now defunct chapbook press and online magazine, even the accused did not know the exact nature of the allegations being leveled against him. Still, the “guilty” verdict on social media was so resounding that his children reportedly received death threats and had to be pulled out of elementary school.

In his landmark work, Violence and the Sacred, French anthropologist Rene Girard cautions individuals against taking justice into their own hands, arguing that the ensuing retributions will spiral out of control, and there will be nothing left. He upholds the value of detached, objective third-party justice systems, such as courts, tribunals, or other formal conflict mediations, as a way of taking revenge out of the hands of the people, and protecting communities. This book, first published in 1972, seems chillingly prescient in light of recent developments in the arts.

Though most of us know that mob mentality in real life is a dangerous and ill-advised, we as a culture have not yet developed the wherewithal or the tools to properly mitigate its dangers in the digital realm. Perhaps because of their newness, many digital spaces lack the sanctions of physical ones. For example, in a court of law, there are clear and standardized definitions of crimes, a limit to how many times a person can be tried for the same offense, and even more importantly, a maximum sentence. The main problem with crowdsourcing social justice in this way is that the punishment becomes arbitrary, and in many instances, disproportionate, unfair, and cruel.

Case in point: after publishing a poem in an arts magazine, Y, another accused person, faced a six-month Twitter storm, replete with death threats, epithets, and allegations of white supremacy, though it not clear whether Y is of white decent. For Y, who is not himself a Twitter user, this punishment seems quite steep for the initial offense, a crime which was at worst publishing a poem that was not fully realized or failed somehow in its artistic vision.

The imprecision of digital justice seems inevitable, given the circumstances. The vocabulary we as a culture have developed for speaking about abuses of power is fairly new and requires refinement, which can only happen with the grace of time. More often than not, mere conflict, or an unpopular opinion, is presented as “abuse,” and there is not yet a shared language for situating misuses of power and privilege on a spectrum. A single instance of verbal harassment seems a much lesser offense than being, like I once was, physically attacked in a deserted train station.

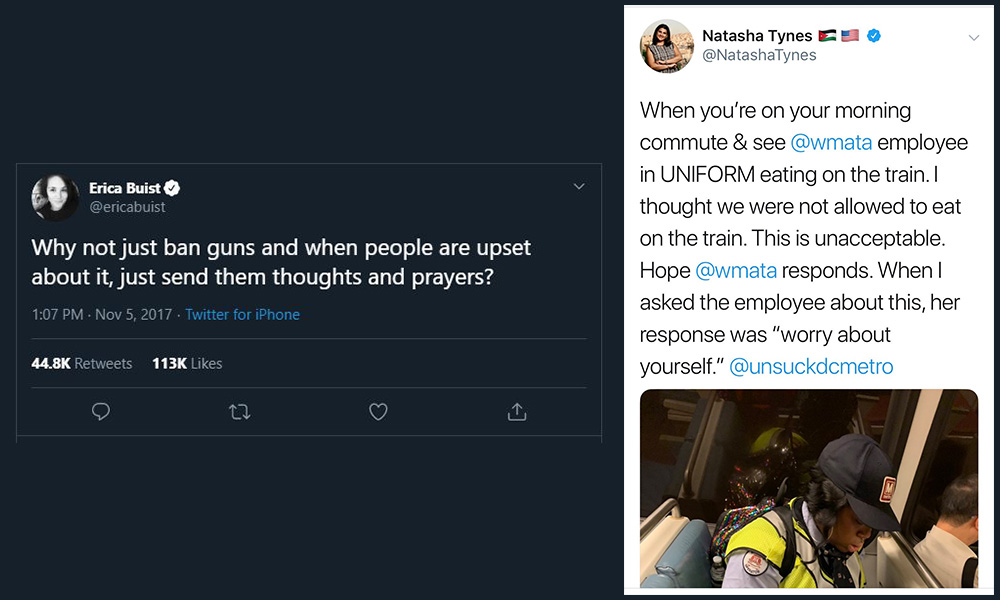

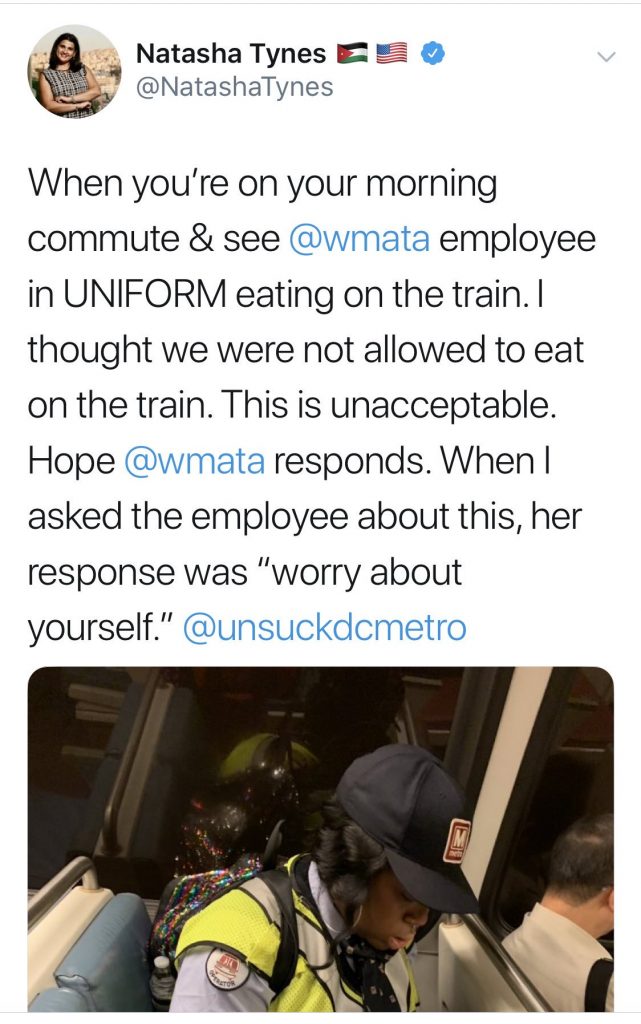

Despite the obvious imprecision of this digital vocabulary, the palpable threat posed by twitter mobs frequently crosses over into the realm of the tangible. In an article as recent as June 10, 2019, The Cut reports that Natasha Tynes, a noted Jordanian-American writer, lost her book deal, her livelihood, her physical safety, and her life as she knew it when a Twitter mob came for her. She had posted a photo of a transit worker eating on the subway, simply stating that it was against the rules.

Though the tweet was undoubtedly in poor taste, and perhaps a bit mean-spirited, the consequences Tynes suffered seem to greatly outweigh the initial offense, as is often the case with Twitter mobs. Buzzfeed reports that she returned to the Middle East earlier this year because the persecution she suffered in the United States was too great for her (or anyone, really) to bear.

I live in fear of my Twitter feed. Every day that a digital mob fails to show up at my door, I count myself as lucky. But what have you done?, even my closest friends will ask. The answer, honestly, is nothing. I haven’t committed any grave offense against my community, but I could be next in the sense that any of us could be next.

The effect that this fear, which oscillates between an indeterminate shame and a more broadly conceived social anxiety, has had on my writing practice might be irreparable. Like many writers of my generation, I find myself self-censoring, holding back in sheer dread of being polemical, being screenshotted, or even worse, both. The witchhunt culture to which we’ve grown accustomed is gradually internalized, and we begin to cross out our most intimate thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions.

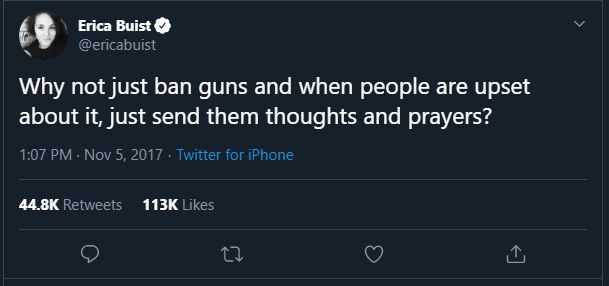

And it’s not just me. Erica Buist, a staff writer for The Guardian, posted a tweet about gun control, which garnered thousands upon thousands of likes, retweets, and responses.

Later on, I asked Buist if she wrote during the week she went viral. “I remember I was wearing a FitBit the week I first went viral,” she said, “and I decided to turn off my phone and go for a walk. I climbed a hill and when I got to the top, I noticed my heart rate was lower than it had been earlier in the day after five minutes on social media. That’s when I realized that the reason I wasn’t writing was simple stress, nerves, jumpiness, and distraction. It’s like trying to write in the same room as hundreds or thousands of people who are all either cheering or jeering at you.”

And Buist is right. The deep solitude that creativity requires is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve given the connectedness to which we as a generation have become accustomed to. Of course, it is this same connection to a community that holds us accountable, makes us behave ethically and mindfully. Yet it is also the omnipresence of social media in conscious experience that polices our thoughts, our writing, and our creativity. If a voicing a given argument, thought, or viewpoint would elicit a reaction, the vast majority of us would simply rather not.