Call the bruise the contusion of one world onto another. I only saw the bruise the morning after I was punched, a blue-purple curl under my right eye, blossoming to two inches across at its longest measure. I wasn’t hit in the eye, but on the side of my head, right where the arm of my glasses stretches from cheekbone to ear. As I slept, gravity and physiology brought the blood to the place where it pooled.

The guy sucker-punched me, a minute after shoving me while accusing me of shoving him. In between those actions he found time to air-punch past one of my friend’s ear, thankfully not hitting her. I was walking with two friends in the park and it was midafternoon on a warm day in early summer. My friends, new friends to me, did not know my history of being punched by bullies in childhood. The temporary occupants of a blurred world, we were crossing a street against oncoming traffic, trying to get away from our attacker.

For many years of my adulthood I have lived punch-free. I have lost track of the fact that, to some eyes, I might look like I need a fist. Forty years old as of this writing, I have a soft face, wear large black-framed glasses, am topped by a great mass of curly black hair. Later, in the evening, my eye not yet visibly bruised, I went into a liquor store and bought a bottle of amaro, its ruby red color taken from cochineal insects, its flavor bitter and soothing when served over ice. The woman who checked my ID was surprised by my age. “You look young,” she said.

I would put the guy at five foot nine, 160 pounds, very wiry. His skin was dark black and his black hair looked like several weeks of scraggle grown out of a short cut. I guessed at homelessness and mental illness. He cursed the word “faggot” at me. The two new friends with whom I was walking are young women. All three of us are white, and we looked as if our clothes had been in drawers, on hooks, in closets the night before. I could not tell if we were victims of a psychotic break, of rage burning out of the violence of poverty, of other prejudices. I do not know the content of the man’s world. My own head had been full of Coleridge’s poem “Constancy to an Ideal Object” at the exact moment I realized we were being followed. I was thinking about that poem, which one of my new friends had sent to me, and looking at a scrim of water veiling a marble god on a nearby fountain, when I noticed the guy shuffle towards us, too close already.

When I woke the next morning, it was as if I had brought the bruise with me from my dreams. My sleep would have felt safer with a companion. I was traveling alone. I longed for something John Berger once described: “Remember what it was like to be sung to sleep. If you are lucky the memory will be more recent than childhood.” I wanted that singing, but also someone around to check me for concussion. The bruise reminded me of the sweet berries I once picked near my uncle’s house, on a small island off the coast of Maine. So few things in visible nature are that exact color. Against it, the faint lines under my eye showed more vividly than they normally do against my skin’s olive tone.

It was, experience tells me, a tremendous blow. Having dealt it, though, the guy had just stood there, his hands held up in a cartoon fighting posture. He seemed to want me to hit him back, to shift the scenario so that it was not a simple case of assault but rather a contest of force against force, but we just made haste to get away. I worried for my friends’ safety and for my own, not knowing if the guy might have a knife in his pocket. And it seemed clear to me that more than enough violence had already been visited on our attacker. When I called the police to report the incident, anxious that the man might hit someone else, or harm himself, I dialed the number for social services as well.

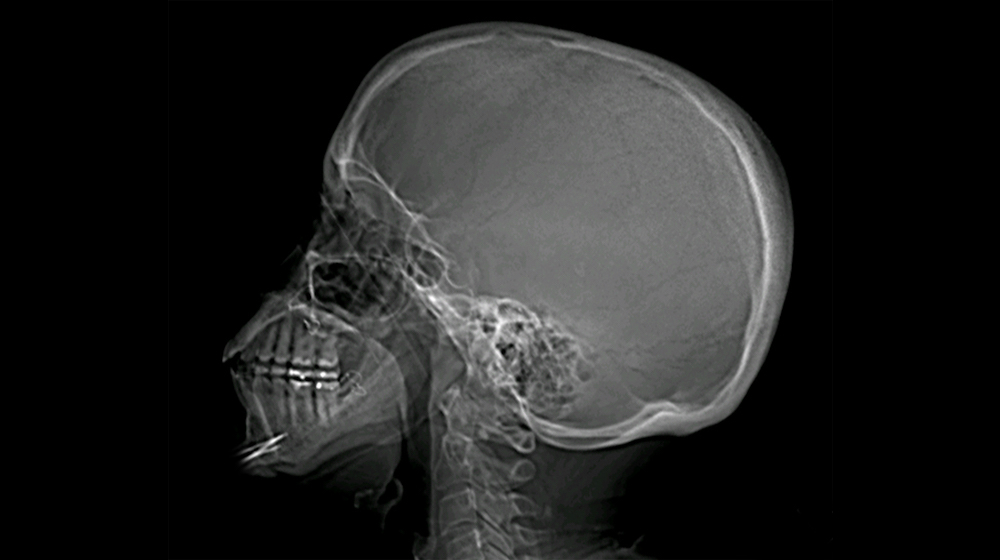

My bruise, I learned a month later, was the surface index of a fracture. The first doctor I saw missed it, but the gummy and soft feeling along the side of my skull — and the way a ridge of bone seemed out of place — sent me to a second doctor. The interior of the mouth is densely innervated, and oral sensations can feel gigantic, out of step with their scale: a tiny chip on a tooth becomes a jagged mountain range as the tongue runs along it. I touched my cheek and felt a similar kind of magnification. The second doctor sent me to get a CAT scan, worried not about my skull, which she, too, judged sound, but about a major blood vessel just under the place my attacker hit me. Freshly worried about my risk of subdural hematoma, I lay in the machine. The ceiling of the room was decorated with a photograph of pink cherry blossoms against blue sky. I thought of a particular park in Tokyo, where I once ate lunch. I thought of my assailant, of how unlikely it was that he had seen that park, and about the probable gulf between my access to doctors, and his.

The scan showed the break in my zygomatic arch, the formation of bone running from near the ear to the cheek, and pencil-thin at the point where the punch landed; the difference I had noted, between the bone structure of my left, uninjured, side, and my right, was real. “You’ll want,” the second doctor said, “to make an appointment in Facial Plastics.” “Facial Plastics?” I asked, and received confirmation. I looked at my face in the mirror, suddenly aware of my vanity, an attitude I normally hide from myself. I wondered if the injured cheek had taken on a different curvature. I drove to Maine and spent a week at a lake, and each morning it seemed that my bone had moved subtly back towards its proper position, as if it were retracing its original line. I hoped this was the case.

During our appointment, the plastic surgeon ran his finger over the concavity in my bone, which seemed to my fingers like a great bowl or valley in my skin, but was utterly invisible to the eye. He told me that the bone seemed well healed. The concavity had no medical consequences, although there was a surgical procedure to re-break the bone and reset it, a procedure with — he said this part carefully — a 50 percent success rate. We looked at one another and chuckled, agreeing that there was no need for elective surgery to correct an invisible dent in my skull. I still have the habit of touching the dent from time to time. It seems to heal ever so slightly with the passing days, but may never vanish completely. One detail from the waiting room at Facial Plastics sticks with me. That room, paneled in dark wood, features curious lampshades. They are decorated with images taken from the journals of colonial explorers in the Americas, and show natives in all manner of local dress, skins dark against the tan background, illuminated by the bulb behind. My skull bears its invisible souvenir of violence into a world where violence often enjoys invisibility, a largely punch-free world.