This past summer, I started writing down sentences that I encountered and liked (in my reading, in conversation, in the wild) and collected them in a little digital sticky note on my desktop. Here are eight:

1. “Everything tasted like an almost epiphany.” — Carmen Maria Machado, In the Dream House

2. “These people — they adore me, and I couldn’t care less.” — My grandmother over FaceTime

3. “It tastes like burning.” — Lip gloss review by Amazon user horror_lover

4. “Hard to feel you are too tragic a figure when tears mix with snot.” — Heather Christle, The Crying Book

5. “We’re at the Coffee Bean, and there is no solution.” — Nicole Kidman, Bewitched

6. “Even in crisis I maintain.” — Andrea Martin, Difficult People

7. “How come you no hello me when you know me so easy.” — Slang phrase used in Michigan (heard on the podcast A Way with Words)

8. “Writing was holy and he made the girls cry.” — Vivian Gornick, Approaching Eye Level

Looking back over this list, I tried to identify some kind of pattern or deeper meaning. All eight sentences, for instance, are declarative. Three contain similes. Their mean and median sentence lengths (9 and 10 words, respectively) are considerably shorter than average. From these observations I deduce that I’m probably attracted to directness, contrast, and concision — in prose, in art, in life.

But what more clearly connects these sentences is harder to quantify — what writer Brian Dillon would call “affinity.” Dillon himself has been doing this sentence-culling exercise for longer than I’ve been alive, and he’s filled some 45 notebooks with countless turns of phrase that have caught his attention over the years. In the introduction to his recent book Suppose a Sentence, Dillon considers what this decades-long practice has revealed to and about him: “Unconnected to duty or deadlines, to projects per se, [the notebooks] compose a parallel timeline — of what? I suppose the word is: affinity.”

Reading that word affinity felt like turning on a defroster, clearing a windshield I didn’t realize was fogged. I’ve been instructed ad nauseam, in these precarious post-collegiate months, to formulate a rough plan or purpose to lend some shape to my future. Since reading Dillon, I can think of nothing I’d rather do than dedicate myself to the pursuit, study, and appreciation of my affinities. This is too obvious and unoriginal an intention to be profound: the idea of a life rooted in affinity is a close cousin of the KonMari tenet of surrounding yourself with that which “sparks joy,” or the Campbellian mandate to “follow your bliss.” We do and want to do the things we like — duh. Nothing epiphanic here. But in taking seriously my affinities, I want to apply Dillon’s sentence exercise to my life as a whole: to actively seek out and surround myself with the words images colors textures sounds patterns people that I love, and then try to glean something from them. This, of course, is why I and many others write: to share and celebrate the things that I love most, and in doing so understand them better (and in understanding them better, in theory, understand myself better).

This is to say that I love that Brian Dillon loves things and then writes about the things that he loves so that we can love them too, because I also love things, and I love to love things, and maybe the best plan or purpose that I can really formulate for myself right now is just to keep loving things and sharing the things that I love and learning about the things that other people love and thinking about why I love the things I love and why they love the things they love and ultimately just putting love at the center of everything I do always. And maybe that starts with filling up some notebooks with sentences that feel special.

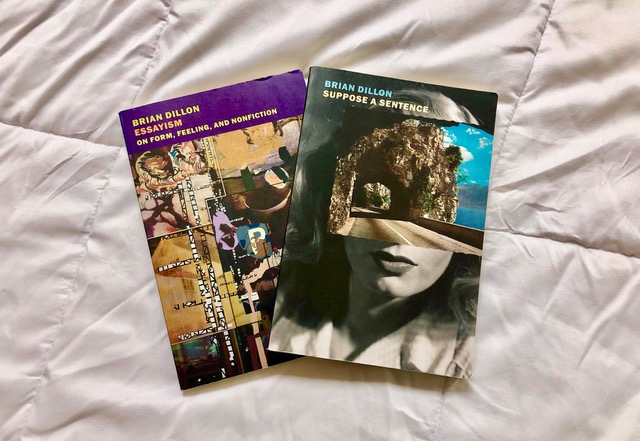

In Suppose a Sentence, Dillon writes 27 essays about 27 sentences, many plucked from his vast notebook collection. The sentences he chooses look nothing like the eight from my sticky note; most are long and dense, full of commas and em dashes and semicolons. They’re the kind of sentences that daunt me, many of them penned by authors (Shakespeare, Donne, Brontë, Woolf) whose work has historically alienated me. This made me all the more excited to read Dillon’s case studies of each one. The second half of Suppose a Sentence features writers whose names, when I spy them printed in the table of contents, make my heart leap: O’Hara, Didion, Hardwick, Malcolm. Funny how the unexpected appearance of a beloved name can inspire excitement or put you at ease, like a familiar face in a crowd of strangers. These are the writers for whom Dillon and I share an affinity, and nothing creates trust quite like shared taste.

I’ve recently developed an affinity for (see also: addiction to) TikTok, and one of my favorite videos floating around there is of a young man passionately defending his love interest to a bus full of skeptics: “She is very gorgeous to me!” he declares, waving a resolute forefinger in the air. The clip cuts off right then, but I really want to hear the rest of what he has to say. What I mean is that Suppose a Sentence is a masterful, meticulous book, at the core of which is Dillon thoughtfully telling me, a sometimes-skeptic, why these sentences are very gorgeous to him.

¤

Prior to Suppose a Sentence, Dillon wrote Essayism, a book-length ode to the essay that blends literary criticism and personal memoir with a care and precision that I haven’t yet seen replicated. In Essayism, Dillon infuses genuine emotion into the serious business of literary criticism and brings a refreshing seriousness to the emotionally indulgent tendencies of personal memoir. It’s one of my very favorite books.

Essayism intimidated me at first. At the back of the book is a syllabus of works referenced, filled with the names of writers that I felt I should know better or like more than I did. Maybe I wasn’t cut out for this book — I wasn’t even an English major. But I’ve always loved essays. My bookshelf, even now, skews inordinately toward essay collections; essays are all I’ve ever written, all I’ve ever wanted to write. So I was pleased to quickly discover that, in its 164 exquisite pages, Essayism is mostly about how Dillon shares my affinity for essays. He deconstructs the genre and, equipped with staggering analytical ability, tries to figure out why it moves him so much. Dillon tells me about “the essayists I admire — no, love” with the authentic excitement of a child who takes you by the hand to show you their treasured rock collection. (To clarify: Dillon’s rock-collection-equivalent is an expertly curated compendium of some of the best writing to ever appear in the English language.) Essayism is free of artifice, devoid of pretension. Dillon simply excavates his unique “aesthetic and intellectual enthusiasms,” as he writes, in an attempt to not only better understand the essay as a form, but also to better understand the ineffable qualities “that I am drawn to in essays and essayists.”

And what is it that he’s drawn to? “Vulnerability,” which he especially admires in Barthes. “Curiosity,” which he sees taken to its extreme in the work of Sir Thomas Browne. And “style,” which he admits might be “what I value, what I love, in essays and essayists,” above all else. “What exactly do I mean by ‘style’?” Dillon asks. “Perhaps it is nothing but an urge, an aspiration, a clumsy excess of admiration, a crush.”

A crush! Crush-having is my area of expertise, the means by which I chronologize my life. I was in fact first introduced to Essayism by a crush. We were talking one evening at the writing center where we both volunteered when he pulled Essayism from his backpack and handed it to me. When he said I could keep it, I knew I’d bestowed my crush wisely. I interpreted this as an act (or was it a performance?) of affinity — for literature, for Dillon, for me.

It felt good to like someone. It feels good to like someone. But crushes on people — for example, on this particular person — can obscure my sense of self. On the other hand I’ve found the kind of crush Dillon describes — on a writer, on a style, on a form — does the opposite; it helps clarify and crystallize. So why do I reserve the language of crushing for people? I feel the same giddy, intense devotion for so many non-people things. I look to Susan Sontag, who, Dillon writers, harbored delightfully specific crushes and catalogued them with care. They included: Venice, tequila, Dürer, silent films, top hats, Bach, ship models, pocket watches, Louis XIII furniture, sushi, and the opera Ariadne auf Naxos. It feels unsurprising that Sontag had such a clear sense of her affinities; she had, at least on the page, a remarkably clear sense of herself. Knowing yourself requires knowing what you like. I’m scared of people who don’t know what they like, and I’m disappointed when people can’t articulate why they like what they like — or worse, when they feel ashamed of what they like. In a life rooted in affinity, there is no room for obligatory consumption or guilt-tinged pleasures. “Anyone who’s worth anything,” Woolf writes in Jacob’s Room, “reads just what he likes, as the mood takes him, and with extravagant enthusiasm.”

Dillon writes in Essayism that, as he was coming into his own as a writer, he was “thrilled and consoled by the idea of writing about something you loved […] so fiercely that you had to uncover whole new worlds of tone and thought in order to describe it.” This feels like an apt thesis for the diptych of Suppose a Sentence and Essayism. Dillon takes his own affinities — those natural, spontaneous, and purportedly inexplicable affections — and mines them for beauty and meaning. I realize now that this is also what I’m attempting, now and always, whether I’m compiling sentences in a virtual sticky note or writing an essay about an author I really like or even just trying to figure out with a friend why I saw A Star Is Born nine times in theaters. I want to document my affinities, understand them, and, with luck, melt them down to make something new. Isn’t that what some of the best works of criticism do?