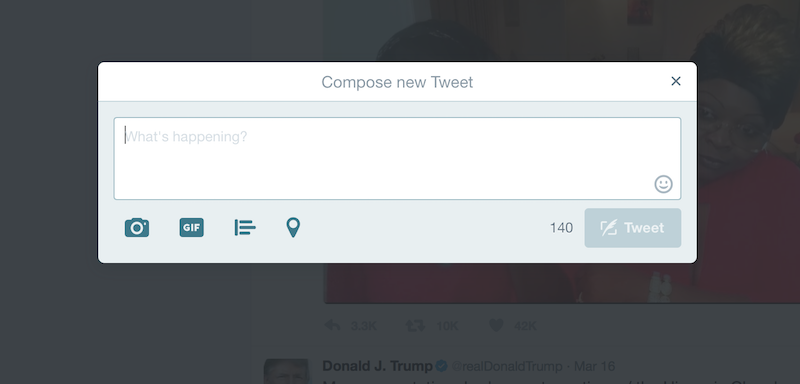

Donald Trump prefers communicating with the public via Twitter, a messaging service that insists a “tweet” be no longer than 140 characters. (As a way of measuring, you should know that the previous sentence — since spaces and punctuation are included in the count — is exactly 140 characters long.) To his critics, this suggests an inability to have long thoughts or possibly Attention Deficit Disorder. But it is worth noting that brevity, while perhaps unknown in previous presidents, is a genre with a long historical pedigree.

In the 17th Century, the French philosopher Pascal was noted for his “Pensées” or pithy remarks. He said, for example, “all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” He also famously wrote to a friend: “I have only made this letter longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter.” (By the way, the shortest letter in the history of Hartford Accident & Indemnity Insurance Company was penned by poet Wallace Stevens who was then a company vice president: “Pay.”)

Certain kinds of remarks are typically short: sayings (“every dog barks in its own yard”), dictionary entries (in Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary: “Oats. A grain the British give to their livestock and the Irish have for breakfast”), advertising slogans (“you deserve a break today”), Zen koans (“what is the sound of one hand clapping?”), and prophecies (that Trojan horse: “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”).

Then there are the epitaphs: on gravestones (television talk host Merv Griffin: “I will not be right back after this message”), the opening dedications of books (Charles Lamb quoted at the beginning of To Kill A Mockingbird: “lawyers, I suppose, were children once”), epigrams or witty communiques (“an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind” by Gandhi; “to err is human, but it feels divine” by Mae West).

Brevity is sometimes related to wit; as Shakespeare’s longwinded character Polonius observed in Hamlet, “brevity is the soul of wit.” This sometimes involves unexpected conversational twists like “some cause happiness wherever they go; others whenever they go” by Oscar Wilde. At other times, wit is seen in memorable insults and ripostes. A hostess meeting Oscar Wilde at her door said: “Mr. Wilde, you are drunk!” His reply: “Madam, I am drunk but you are ugly. In the morning, I will be sober.”

Oscar Wilde was a genius in this genre but so, too, were others like Mark Twain and Yogi Berra, who coined countless witticisms like the chestnut “nostalgia is not what it used to be.” Then, too, there are certain occasions where “zingers” are expected, like comedy routines on TV talk show. Jay Leno observed, “in an exclusive interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network, Donald Trump said, ‘I believe in God.’ But, of course, The Donald was talking about Himself.”

Likewise, there are certain literary forms that prize brevity — the haiku, for example, and the fable. Jorge Luis Borges, the famous blind author from Argentina, preferred writing short stories to penning novels. So, when he got an idea for a novel, he would mention it in one of his stories as if the book actually existed and then give a brief summary of it. Friedrich Nietzsche would have been sympathetic. The German philosopher said, “it is my ambition to say in 10 sentences what others say in a whole book.”

In our own time, no less an author than George Saunders has suggested the same: “a novel is just a story that hasn’t yet discovered a way to be brief.” Responding to this impulse has been the “Flash Fiction” movement, where creative writers aim to tell in six words an entire story that might otherwise require hundreds of pages: “for sale: wedding dress, never worn.”

Indeed, sometimes the loquacious have to be taken to task. Samuel Johnson once offered the last word on the many volumes of Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost: “none would wish it longer.” Still others have felt an obligation to show the loquacious how they could be more economical. In 1980, Maurice Sagoff invented “Shrinklits” and spawned a movement where the world’s classics were boiled down to one-sentence summaries. Homer’s Odyssey, for example, yielded “man refuses to ask for directions.”

Of course, newspapers often do something similar in offering TV-Guide like summaries of what’s on TV. The most famous of these is Rick Polito’s entry for MGM’s Wizard of Oz: “transported to a surreal landscape, a young girl kills the first person she meets and then teams up with three strangers to kill again.”

You’ll find Polito’s summary of that movie everywhere on the internet. “That line is going to follow me to the grave,” he said, and you can see why. Sometimes “less is more,” and Polito’s one sentence synopsis makes you look at the classic movie in an entirely new way. But at the very same time, when you think about everything from Judy Garland to her ruby red slippers, sometimes “less is just less.” And that, more or less, is the situation with brevity itself. In a nutshell.