Arriving in New York City for the first time in 1943, Marlon Brando is alleged to have told a shoeshine man that he had been born in Rangoon, and when asked where that was, to have responded “over there and down a bit.” He told other people he had been born in Calcutta. Neither was true, of course: Brando was born in Omaha, Nebraska. So it is all the more remarkable that Southeast Asia came to figure in Brando’s understanding of the world. And in a way Brando helped to shape American perceptions of Southeast Asia — as a no man’s land somewhere between a China that in 1949 had been lost to communism and the sensuous Pacific devoid of politics. This No Man’s Land was, in the popular imagination, where US foreign policy became wrecked on the shoals of corrupt leaders and peasants who slavishly worshipped power. If a single word came to characterize American perceptions of Southeast Asia, it was quagmire.

While the American public was wilfully ignorant of Asian geography and all too happy to clutch at stereotypes, Brando knew a good deal more. And he wanted to learn. In 1956, already one of the most famous actors in Hollywood, Brando narrated a four-minute documentary for the United Nations Technical Assistance Administration about an American hydrological engineer who helped a village in an arid region of Bolivia drill a well. The well brings water and the water is rich in much needed minerals for a population that suffers from goiter. Even the parish priest, in whose church yard the well was drilled, thought the well was a miracle. The experience narrating the short documentary left Brando so taken by the prospect of a foreign policy that targeted basic needs rather than military installations that he decided he would make UN technical assistance the story line for a feature-length movie. The setting for the film would be somewhere “over there and down a bit” — in Southeast Asia.

¤

In 1956, Southeast Asia was a hot frontline in the Cold War. Two years earlier the French had suffered defeat at Dien Bien Phu. The result, hammered out at the Geneva Conference over the next few months, was French withdrawal from Indochina, the temporary division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel and a commitment to hold national elections within two years. The US responded by hastily cobbling together a new alliance, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, of which only two members — the Philippines and Thailand — were states in Southeast Asia itself. (The other members were New Zealand, Australia, Pakistan, France and the United Kingdom.) At precisely the same time, Indonesia was coming to loom large in American foreign policy. In April 1955, President Sukarno had hosted the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, throwing down a direct challenge to US foreign policy. Five months later, when national elections were held, the Indonesian Communist Party polled surprisingly well, raising the spectre of a second front in the region.

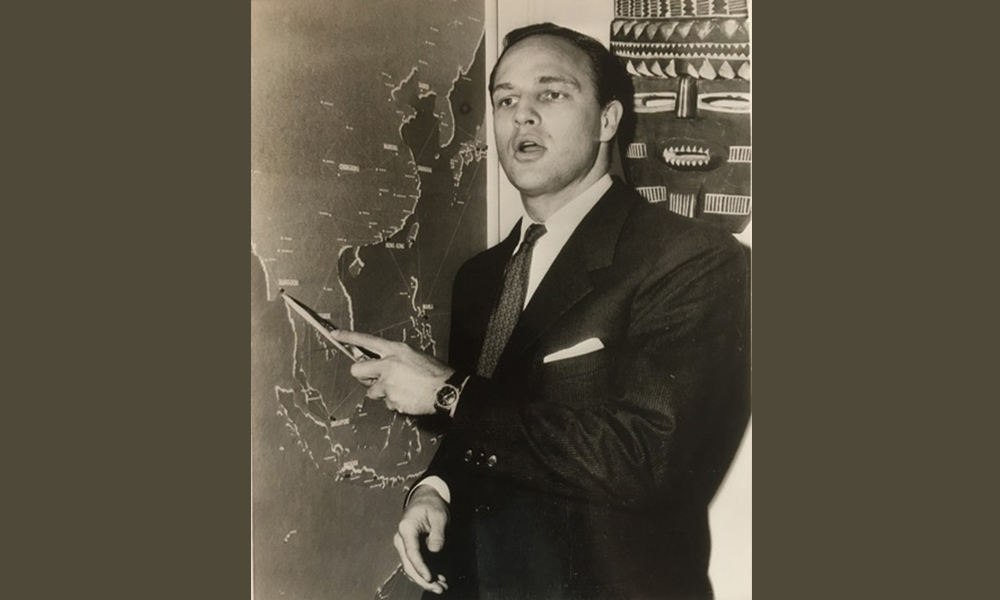

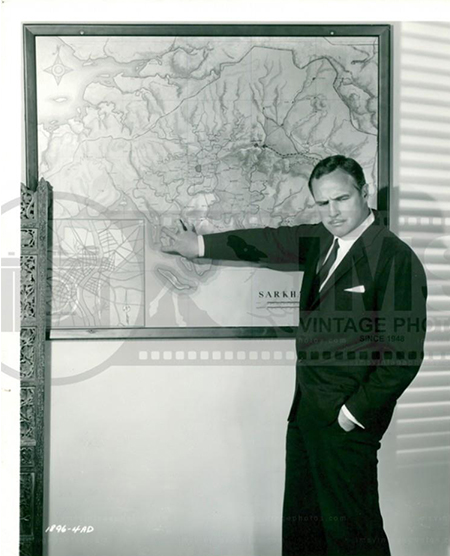

It was in this context that Brando held a press conference in Hollywood on March 1, 1956, to announce that he was about to depart on a 20,000 mile trip to do research for an adventure film about the UN technical assistance program in Southeast Asia. Pointing to Rangoon on a map, Brando said that his itinerary would take him to Manila, Jakarta, Singapore, British North Borneo, Thailand, Burma, and then beyond Southeast Asia to Ceylon, India and Pakistan.

Marlon Brandon points to Rangoon on a map during a press conference, March 1956.

In fact, Brando was scheduled to fly to Japan to film The Teahouse of the August Moon, in which he would play Sakini, an Okinawan reporter. The 20,000 mile research trip was initially a side-show. But Brando soon came to see this in reverse — viewing his role in The Teahouse of the August Moon as a way to finance the new project about the UN and international development. Brando and his close friend and director George Englund flew from the US to Manila (where his arrival nearly caused a riot), then to Hong Kong (where he canoodled with hostesses), and on to Singapore (where his film The Wild One had recently been banned), before heading to Tokyo in early April.

But when filming in Japan concluded, Brando abandoned the plan to continue his research tour to Bangkok, Rangoon, Ceylon and India. Instead, he flew to Bali. George Englund later wrote:

Knowing that we might find a treasure trove of material in Indonesia, Marlon skirted his responsibility by going to Bali. I think he was following an old neurotic pattern, to test the patience of others to its limit with the hope of being called to task and punished. His denunciation of his country at all press conferences was further testing of our patience.

Brando’s own account of the trip to Southeast Asia was modest but far more serious:

From afar, I’d admired the efforts of the industrialized countries to help poorer nations to improve their economies, and thought that this was the way the world ought to work. But I found something quite different; even though colonialism was dying, the industrialized countries were still exploiting the economies of these former colonies.

Brando lamented the “self-serving” purposes of foreign aid and the cloistered world in which Western diplomats and development practitioners lived: “hermetically sealed capsules of villas, servants, bourbon, air-conditioned offices, expense-account parties and all-white country clubs.” His condemnation was sweeping, hitting both American officials and Southeast Asian leaders:

A lot of the foreign-aid officials I met seemed arrogant and condescending, with a smug sense of superiority. Apparently because the United States had more television sets and automobiles, they were convinced that our system was infallible and that they had a God-given mission to impose our way of life on others. I was still unschooled in the ways of the diplomatic world and the hypocrisy of US foreign policy, but I sensed that many of the political orders we were supporting in these countries were looking out only for themselves and their bank accounts. They lived in palaces while their people lived in huts.

There is more here than may meet the eye. Writing his autobiography in his late 60s, Brando was channelling three decade-old memories of Indonesian President Sukarno. In 1955, in his opening address at the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, Sukarno had declared: “We are often told ‘Colonialism is dead.’ Let us not be deceived or even soothed by that. I say to you, colonialism is not yet dead. How can we say it is dead, so long as vast areas of Asia and Africa are unfree.” On other occasions, Sukarno was fond of declaring: “Colonialism is not yet dead. It is only dying.” On the automobile as a symbol of American culture, Sukarno had declared: “We do not envy you all the gifts of your way of life. The two-car garage has little attraction for us, but the health of our children has, freedom from avoidable disease [has], education has.” A dying colonialism and the symbolism of the automobile stuck with Brando.

In fact, Brando had met President Sukarno. This was not during his travels in Southeast Asia in 1956 but immediately after returning to the United States from Bali. On June 1, 1956, Sukarno visited Los Angeles with his family, touring the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios during the day and speaking at a special event at the Beverley Hills Hotel in the evening. (The event started 30 minutes late because Sukarno wished to meet Marilyn Monroe, who was attending a different party at the hotel the same evening.) A New York Times article on Sukarno’s speech is worth quoting at length:

As one who regularly looks at “three to four” Hollywood movies a week, President Sukarno said, “I know some of your pictures are very bad.” He added, however, that in spearheading the assault on illiteracy, movies have “played a great part in the revolutions which have swept over Asia in recent years.” He urged film creators “to be responsible people who understand the great machine you control, and respect its strength.”

Hollywood films may be criticized as being “carefully and deliberately non-controversial” in the Western world, President Sukarno stated. “Hollywood can never be non-controversial,” he added, “so long as democracy, equality of opportunity, national self-esteem are implicit” in its pictures.

The personal meeting on June 1 and Sukarno’s speech that evening must have reinforced Brando’s determination for his new, independent company, Pennebaker Productions, to make films with a message of international cooperation and social justice. Over a period of ten weeks his team prepared a script for the film about UN assistance in Southeast Asia. The title was Tiger on a Kite. But Brando didn’t like the script and the project was put on the back shelf. Instead, Brando signed on to star in a film about an American air force pilot serving in the Korean War who falls in love with a Japanese dancer. (In 1957, Jack Kerouac had sent a letter to Marlon Brando asking him to take the part of Dean Moriarty in the film adaptation of On the Road, but received no reply.)

While Englund was shooting Sayonara in Kyoto in 1957, Truman Capote arrived to interview Brando. Asked about the possibility of a return to performing in theatre productions in New York, Brando pivoted to questions of social responsibility. Through film, he argued, “you can say important things to a lot of people. About discrimination and hatred and prejudice. I want to make pictures that explore the themes current in the world today. In terms of entertainment. That’s why I’ve started my own independent production company.” Sayonara addressed prejudice and interracial marriage (while simultaneously perpetuating stereotypes about Asian women), but it was a far cry from a statement about international cooperation.

Meanwhile, US involvement in Southeast Asia was intensifying rapidly. With a sharp rise in communist attacks in late 1957, the US continued to bankroll the Diem government in South Vietnam, to pay the lion’s share of the military budget, and had introduced military advisors. In mid-1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer’s lightly fictionalized The Ugly American was published, detailing the failures of American foreign policy and military involvement in the region. The fictional country Sarkhan was clearly meant to be the American-backed Republic of Vietnam; and the main character was based on CIA operative Edward Lansdale. Further south, the CIA was actively aiding regional insurgents in Sumatra and Sulawesi who had taken up arms against President Sukarno and declared a rival Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia. Covert American assistance to the rebels was fully exposed when the Indonesian armed forces shot down a CIA airplane providing supplies and captured the pilot, mercenary Allan Pope.

¤

It was not long before Southeast Asia was back on Brando’s radar. In 1962, Brando agreed to star in the film adaptation of The Ugly American. Adaption is perhaps too generous, in fact, for what was borrowed was merely the title, setting, and naïve American officials in Asia. The plot was entirely new. George Englund, who had accompanied Brando on the 1956 trip, was the director. Brando played American Ambassador Harrison MacWhite. Japanese actor Eji Okada was cast as the Sarkhanese liberation leader, Deong. After a failed search for an actor who fit the role of the Prime Minister of Sarkhan, Englund enlisted Kukrit Pramoj, who was a great grandson of Siam’s Rama II (and who in 1975 served briefly as prime minister of Thailand).

In an early scene, members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee question the nominee for ambassador, MacWhite (Brando), about his friendship, dating from World War II, with a Sarkhanese leader. “Is he a ‘Red’?” the senator barks. “He’s no such thing,” MacWhite replies, “he’s a nationalist.” Arriving in Sarkhan, MacWhite is welcomed by an anti-American demonstration that turns violent. He is determined to whip the embassy staff out of their complacency, sort (pro-American) friend from (communist) foe and get on with business – including construction of the Freedom Road. Soon after, however, MacWhite visits his old friend Deong, gets smashed on rice whiskey and concludes that Deong is not only a communist but was behind the anti-American demonstration opposing his appointment. A cocksure MacWhite insists that the only way to counter the communist threat is to push through with building the Freedom Road to the north, rather than divert its route, as advisors had recommended, thereby bringing progress and development to the northern part of the country. A New York Times review praised Brando’s acting but called the movie’s plot “corny, calculated and naïve.”

Today, The Ugly American is perhaps best remembered for depicting how a combination of crude Cold War calculations in Washington, DC and earnest but bumbling American officials on the ground led to what was once America’s longest war. But for Brando, the film represented something far more specific: it was simultaneously the fulfilment of and reckoning with his idea seven years earlier to make a film about the potential for technical assistance and social justice. Brando surely knew that the fictional Freedom Road, which was billed as a Sarkhan-USA joint highway project, was modelled on the Asian Highway. And he must have sensed that this represented a historic shift in geopolitics. The significance is borne out through comparison.

The rose-colored map may be the most famous representation of an empire on which the sun never set, but there is perhaps no better symbol of British hegemony from the early 18th until the early 20th centuries than the chorus of the song Rule Britannia: “Rule, Britannia! Britannia rules the waves; Britons never, never, never will be slaves.” The notion that Britain ruled the waves persisted for a time after World War II, when decolonization was set in motion, and with it British rule in Malaya and Singapore, as well as most of Britain’s colonies in Africa. It is little surprise, therefore, that for Indonesian president Sukarno the “life-line of imperialism” was the maritime link stretching from Europe to the Far East:

This line runs from the Straits of Gibraltar, through the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea and the Sea of Japan. For most of that enormous distance, the territories on both sides of this lifeline were colonies, the peoples were unfree, their futures mortgaged to an alien system. Along that life-line, that main artery of imperialism, there was pumped the life-blood of colonialism. (Sukarno, opening address at Bandung Conference)

True enough. But by the late 1950s the life-line of colonialism was being overtaken by the choke-hold of containment.

In 1959, the United Nations announced an ambitious new program to construct a great Asian Highway, dubbed the A1, which would start in Istanbul and run through Turkey, Iraq, Iran Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Burma, Thailand and Cambodia to its immediate terminus in Saigon, South Vietnam. With dreams of eventual capitalist victory, the A1 was slated to extend north from Saigon through the (communist) Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the People’s Republic of China, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea all the way to Seoul, and then by ferry, to Japan. (The plans called for a second branch, the A2, to run from Thailand south through Malaya to Singapore, and then across Java to Bali.) This ambitious project would be made possible thanks to American financing, for it was, in essence, an American scheme intended both to promote development (read: capitalism) in the countries through which it passed and to serve as a buffer against the communist block to the north.

Cold War concerns ensured that generous American funding was channelled through the United Nations to countries participating in the Asian Highway project. Practical guide maps for motorists were even issued for each of the major sections: Iran-Afghanistan-Pakistan, India-Nepal-Burma, and Thailand-Malaya-Singapore. Work proceeded in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Thailand, with promotional photographs released of men clearing roadbeds, crushing rocks, and directional signs. But political obstacles soon emerged. In 1962, General Ne Win seized power in Burma and his new regime declared an autarkic policy dubbed The Burmese Way to Socialism, effectively ruling out any foreign involvement. In 1971, the Bangladesh Liberation War raised another barrier in the route of the A1. With the communist victory in Vietnam in 1975 American financial support dried up and the fiction that the road would ever lead to Seoul and Tokyo was abandoned. The final straw came in 1979 with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan the Iranian Revolution. What had been envisioned as an integrated system of American containment had become a piecemeal sieve of international goodwill.

¤

It is perhaps an appropriate coincidence that the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan coincided with the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, starring, of course, Marlon Brando. The actor’s early enthusiasm for a foreign policy that targeted basic needs was gone, replaced in the film by a hall of mirrors in which the horror of King Leopold’s Congo was now America’s war in Vietnam and America’s war in Vietnam had become the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The best American policymakers could hope for was to assassinate their own (Colonel Kurtz) and provide arms to their enemy’s enemies (the Mujaheedin).

But the wheels of time turn ever forward. Twelve years after Brando’s epic return to a celluloid Southeast Asia, the collapse of the Soviet Union brought fantasies of the end of history. With this, in 1992 the Asian Highway was revived, now under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, and was expanded to include the Asian Highway, a Trans-Asian Railway and a host of supporting land transportation projects. But without the imperatives of the Cold War and America’s newest (and now longest) war in Afghanistan, donor support was spotty and actual work was patchy. Into this void stepped Premier Xi Jinping with his Belt and Road Initiative that promises massive investment to create “connectivity” across the length of breadth of the Eurasian land mass. This is equal parts good will and diplomatic leverage; economic stimulus and an outlet for Chinese capital; integration and a rapacious grab for natural resources.

Over there and down a bit, the ugly American has been replaced by the ugly mainland Chinese tourist and, increasingly, the illegal mainland Chinese worker. The terms of engagement have shifted as well. Brando spoke out against a foreign policy dictated by self-interest; his character Ambassador MacWhite brought that hypocrisy to the big screen. Today, in contrast, the Chinese vision of Southeast Asia is of a land of opportunity for investment and tourist selfies. In place of Brando’s Ugly American, the highest grossing PRC film about the region was the 2012 adventure-comedy Lost in Thailand, whose popularity at home fuelled a massive influx of tourism to Chiang Mai, where fans sought out the locations shown in the film. Chinese tourists swamped the campus of Chiang Mai University, where they took over the cafeteria, sat in on classes they couldn’t understand, and some are even reported to have defecated in the moat that encircles the campus. Fed up, university authorities posted guards and now require Chinese tourists to show their passports and take guided tours.