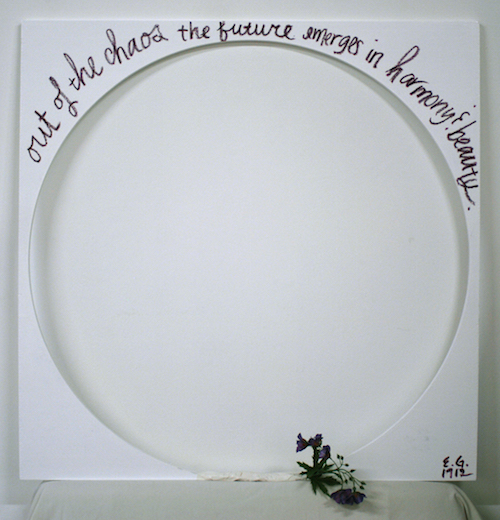

“Out of the chaos, the future emerges in harmony and beauty.” – Emma Goldman, 1912

When it became clear that Hillary Clinton had lost the election, I saw numerous posts by friends saying that their daughters were inconsolable. Possibility and potential fell before their eyes.

Suffice it to say, 2016 was a bad year for women. Still reeling from the election on the first day of winter break, I grabbed my coffee and headed to a loft not far from mine in downtown Los Angeles. I located the building and headed up to knock on the door. A few minutes later, the door opened. “I’m early, right? Sorry,” I said. “Should I come back?” My apology was shrugged away with a smile, and I was waved into the studio where I was to become, briefly, via makeup and clothing and tricks of light, a woman from the past, someone brave and revolutionary.

A few weeks earlier, I had received an email from artists Allison Stewart and Mary Anna Pomonis, inviting me to participate in their project called “Resurrecting Matilda.” The note asked me to “embody a favorite woman from history” and even offered with help in getting a costume. I said yes right away, something I only do only when I absolutely do want to do something and yet am just a little afraid that I might back out if I don’t commit quickly.

But who would I be? It was hard to choose. At first, strangely, I couldn’t think of anyone. Then, for a while, I fixated on the artist and former nun Corita Kent, who had inspired me since high school with her positive approach and radical politics. I knew I wanted to be someone that had a strong activist history and powerful beliefs. Surely there was a plethora of people to choose from — why wasn’t a blizzard of brilliant and powerful women springing into my mind?

Maybe I was tired. Maybe I was overworked. I would think about it later. That’s what I told myself, but “Resurrecting Matilda” offers another view; Pomonis and Stewart were initially inspired to create this project because of a historical erasure of women. Pomonis described the experience of her sixth grade daughter coming home with an Ancient History textbook, which Pomonis was excited to look through because she had been researching Enheduanna, a Sumerian poet who invented poetry and was the first writer to use the first person. Upon discovering that Enheduanna wasn’t included, she scoured the book, and realized that women were mostly missing, or their contributions were downplayed. She said to Stewart: “How could a woman whose work was so important in terms of invention and consciousness to all of civilization be completely left out?”

It’s old news that women are not included as often in history. But was it really possible, even with my two degrees and years of working in the field of art and around issues of social justice, I didn’t know enough about the historical accomplishments of women? My questions led me to another heroine: Allison Krause, the young woman who was killed at Kent State in 1970, shortly after placing a daisy down the barrel of a National Guardsman’s gun. I knew the famous photo of her, taken shortly before she was killed, and had included a reference to her in my novel, Mayday, of a woman that tried to change the world by passing out flowers for hope.

I felt a kinship with her; in another time and place, when I was her age, I could see myself meeting the same fate. Age aside, I wondered, was one action enough for a historical survey?

Who decides what merits a valuable contribution; what is important and who is remembered? Pomonis and Stewart both celebrate and challenge these questions with “Resurrecting Matilda.” They didn’t come with a prepared list of subjects, but with an idea and curiosity. By asking women to choose who they want to include in this particular “canon,” the artists take a collaborative and open-source — in other words, a traditionally feminine — approach to historical methodology.

The title is inspired by “The Matilda Effect,” a phenomenon named for women’s rights activist Matilda Joslyn Gage, that refers to female scientists being left out of history, their accomplishments credited to their male peers. The participants are contemporary and mostly Los Angeles-based artists, writers, and scholars. The subjects they portray comprise a powerful list, 19 and counting, of women’s accomplishments with a marked and vibrant diversity of time and place, including Himiko, the shaman queen of ancient Japan, to Aethelflaed, the Anglo Saxon warrior and leader that helped stave off a Viking invasion, to 17th century Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi, 20th century Guatemalan teacher and martyr María Chinchilla Recinos, to the contemporary American activist and professor Angela Davis.

After a few indecisive texts to Mary Anna, I settled on my own subject: 20th century anarchist Emma Goldman. I share her radical progressivism, love of writing, and passion for social change, and am inspired by her powerful belief in anarchism as a means to human freedom and equality. But in the end, it felt right not as much because of what we had in common, but what we didn’t; there is much to admire about the renowned anarchist, but what I love most is her fortitude and courage, and the attitude of not caring what what others think of her and her incessant drive in the quest of equality and justice for all, all qualities I strive for.

I first learned about Emma Goldman on a work-for-hire writing assignment; poetically, considering this project, it was a textbook on anarchism. I researched and translated the histories and ideals of this fascinating thought process and practice of the early 20th century, all the while imagining how a contemporary teenager finding this slim volume in a library and picking it up might respond. I read Kropotkin, Proudhon, and Bakunin. Unlike the bomb-throwing extremism typically associated with anarchism, I came to see that it was an idealist philosophy of self-governance based on mutualism and shared support. And, unsurprisingly, most of those that I read and researched were male. And then there was Emma Goldman, a hero of the movement and one of its staunchest supporters, championing the rights of workers, women, and children equally through her speeches, writings, and organizing.

In Emma, I find so much that is contradictory and real. As I researched her photos for this project, despite the idealism I so admired, I saw the same stern, unsmiling face in all of them. In most, her index finger lay against her cheek and the rest of her hand curled in a tight fist.

In nearly every picture taken of me since I was a very young girl, I have the exact same smile. My late father and I had a lot in common, including that one funny trait, a very consistent smile, but there is one photo of us, taken at a cotillion dance, in which I am looking seriously over his shoulder and into the horizon. My dad loved that picture, and I never knew why. I wonder now if it was because he saw something in me that I have yet to see myself, or am maybe only beginning to see, two decades after his untimely death.

The night before the photo shoot, I decided that I had better try to get the look down. I brought my iPad into the bathroom with the photograph on the screen and practiced the pose and gaze. I tried to feel it in my body — the stretched finger and clenched hands, the erect spine and strong shoulders, that steely gaze, and one hip tipped ever so slightly, sassily, to the side.

Back in the studio that Sunday morning, Allison and I sat and chatted about the project. She told me that there was a moment in every shoot where the subject became the woman she was posing for and that was when she knew she had it. I listened, wondering what that looked like and if I would get there. Before long, Mary Anna came with a white shirt, floppy hat, and another essential prop, the glasses with one arm and a long chain or ribbon down the other.

I dressed and stood against the window facing the street. I propped my arm on a stack of books and looked just beyond the camera into the distance. The glasses fell and I had to pick them up. Even after we added shoe boxes, the table was too short and I stood with bent knees trying to keep my torso upright, my hip popped, my finger extended. “Clench your fist,” Allison coached. I took a breath. I gazed into the lens. I felt, for a split second, a sense of power and ease within the tightness and effort. Yet I don’t know if I achieved that transformative moment or not.

Heroes and heroines are not mirrors, but sparks held aloft to light the grey mist of questions we move through most of the time, unknowing exactly what will come next or the eventual outcome of our efforts. They inspire us to be better and stronger versions of ourselves, to look past now and into tomorrow, not to who we are, but to what we might become.

Now more than ever, it is vital that our girls are given opportunities to see their potential, to gain a glimpse into their brightest possibility, to learn about the strengths, successes, and struggles of the women that came before them. It’s time to resurrect an army of Matildas.

Header image: For Emma, Annie Buckley, 2012, found wood, plastic flower, oil pastel, and tape