To understand Steve Bannon’s post-White House political activities, you have to understand how deeply Bannon — an avowed Shakespearean — completely misunderstood all the important lessons the Bard has to offer. Barely out of the Trump administration a few months ago, Bannon unleashed total war on the political establishment. “I’m free, I’ve got my hands back on my weapons,” the former White House Chief Strategist purportedly told his friends. With an unleashed Bannon back at Breitbart, a civil war of sorts seemed the logical end result. Even conservative pundits like Charles Krauthammer predicted a “bloody affair.” Bannon initially avoided an all-out confrontation with Trump and took on the entire Republican political machine, vowing to wage war against all GOP senators up for reelection except Ted Cruz. But after going all in for Roy Moore last month, Bannon was forced to witness not only his candidate’s historic, humiliating loss to a Democratic contender in ruby-red Alabama, but also his former boss’s Twitter jabs at Moore: “The reason I originally endorsed Luther Strange (and his numbers went up mightily),” Trump tweeted in an awkward about-face one day after Doug Jones won the race, “is that I said Roy Moore will not be able to win the General Election. I was right!” The time for the highly-anticipated fratricidal carnage promised by Bannon last summer seemed finally upon us.

Before selling his dark vision of a globalist America overrun by foreigners and torn by intestinal strife to the Trump campaign during the 2016 election, Bannon, a “bitter Hollywood wannabe” during the ‘90s, once wrote Andronicus, a sci-fi adaptation of Shakespeare’s classical tragedy, complete with scenes of intergalactic sex and violence. A Leni Riefenstahl aficionado with a passion for the classics, Bannon had flirted with Shakespearean Roman plays a few years earlier, trying to turn Coriolanus into a rap musical set in South Central Los Angeles during the Rodney King riots. Though his infatuation with Titus Andronicus, a theatrical gorefest featuring acts of dismemberment, mutilation, and cannibalism, dates back to his short-lived Hollywood career, his interest in it seems awfully prescient today and raises interesting questions and parallels with Shakespeare’s revenge extravaganza.

The Andronicus story involves a state of planetary chaos and an intergalactic mission led by Titus to save Earth. The description of the opening scene reads like a nightly newscast these days: “Humanity in chaos. Alien ships sweep out of dark, sunless skies as people flee in panic.” But, in the end, recasting Shakespeare’s story of moral and political decay as an intergalactic battle proved unsellable. The production never materialized and, a few years later, Bannon became an executive producer for Julie Taymor’s 1999 film adaptation of the play. (Taymor, though, has issued a public disclaimer stating that, although listed as one of the executive producers, Bannon had actually no artistic or financial involvement in the production of Titus.)

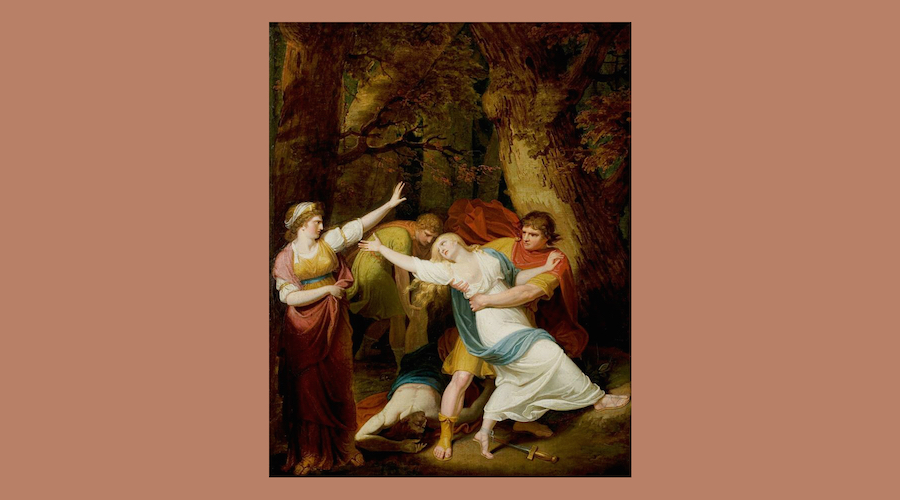

Shakespeare’s original play is a dark reflection on the collapse of boundaries between civilization and barbarism. It tells the story of the eponymous Roman general who, after defeating the Goths abroad, returns home amid a fierce power struggle triggered by the death of the Roman Emperor. Titus makes one political blunder after another, refusing the throne and unwisely backing Saturninus. He kills his youngest son Mutius out of a blind loyalty for the Emperor, who quickly proves unfit for office by deciding to marry Tamora, Queen of the conquered Goths. The alliance between Titus and Saturninus quickly unravels, and the two become mortal enemies in a bloody revenge cycle that wipes out almost the entire cast by the end of the play.

In the opening of the play, Titus sacrifices Tamora’s eldest son as part of a religious ceremony meant to appease the Roman gods. His violent action sets in motion the revenge plot, in which Tamora and Saturninus begin to systematically slaughter the Andronici. The general fights back by preparing a cannibalistic feast for his enemies, who unknowingly consume the flesh of their own children baked into two scrumptious pies. The play ends with Titus’ son, Lucius, being proclaimed Emperor and retaliating against the foreign Goths, who are blamed for the violence and moral corruption in Rome.

If Shakespeare’s revenge story strikes an all-too familiar chord, it is precisely because it ends on a dark, ominous note reminiscent of our own political ills and divisions. The deeply fractured society of Rome, as well as the fratricidal violence endemic to it, is ironically cured by being scapegoated onto a foreign other. The play’s metaphorical arc is oddly prescient today: it begins with a primitive blood ritual, in which a “barbarian” is sacrificed to appease Rome’s desire for revenge, and ends with the specter of insanity, treason, and cannibalism, a potent image for the political infighting that destroyed the Roman Empire.

There is quite a bit of tragic irony in the Trump/Bannon story. Clueless about Shakespeare’s history lessons, they both seem doomed to repeat them over and over again. If Titus can teach Bannon or Trump anything, it is that the destruction of a political body does not come from without, but rather from within. Shakespeare’s deadly cycle of revenge shows that Roman civilization cannot remain immune or insulated from the violence it perpetrates on others. The “noble” patricians wreak havoc in Rome on a scale that the “barbarous” Goths can hardly match. As the bodies are piling up outside the White House, it would be prudent for Trump to heed, like Shakespeare, the lessons and stories of the past.