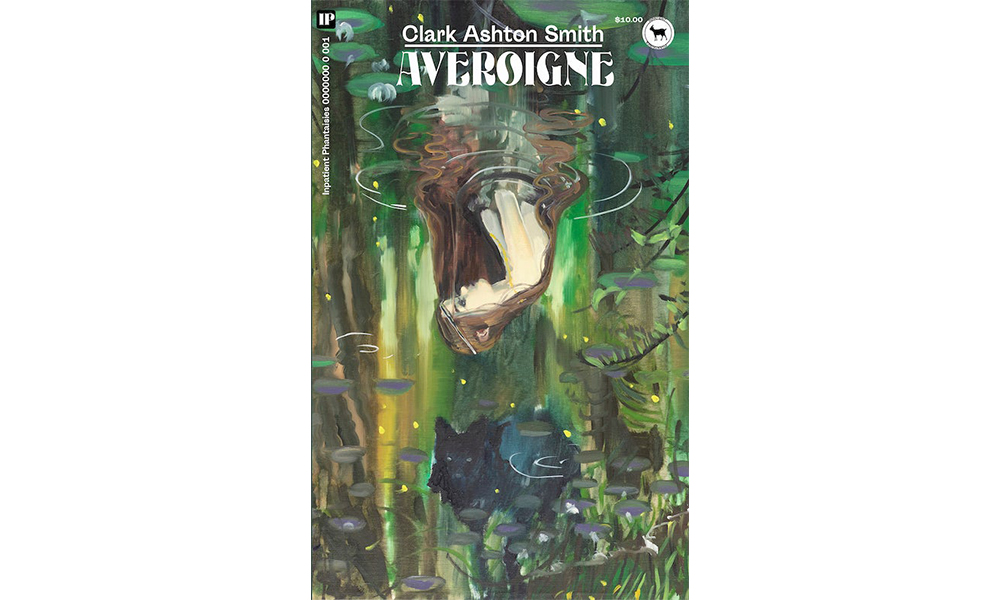

When my partner Enzio di Kiipt and I began work on the Averoigne project, our founding imperative was — and still is — to bring the seminal work of Clark Ashton Smith to as many fine readers as possible and see that his legacy as an unparalleled crafter of paracosms continues to inspire.

As the newly anointed Executive Executor of CASiana Literary Enterprises, it is my esteemed honor to present to you the following introduction written for Averoigne by my dear friend Kit Schlüter. With Schlüter’s keen etymological eye, Smith’s vocabulary is situated as a revitalizing force of history itself, each word a primary document, some laying fallow for centuries until the intrepid linguonaut uncovers them and lets the story of the words be told. Intertwined with Schlüter’s own recollections of his days in the decaying French department of Aveyron, it is a graceful and encompassing entryway to the world of Averoigne and Clark Ashton Smith. I am indebted to Kit for writing it and to LARB for presenting it here.

— M. E. Anzuoni, Publisher of Averoigne

¤

Unswerved by shattered worlds upbuilt once more.

— Clark Ashton Smith, “Ode on Imagination”

In 2011, after finishing my studies, I took a job in the French town of Villefranche de Rouergue as the public school English teacher. Nestled in the verdant crease of the Aveyron Valley, this once thriving, largely Occitan-speaking place is dominated by the 13th century church that towers over its central Place Notre-Dame, the moribund Christ surveilling all from his cross on the outlying calvary hill, and the Gothic monastery, La Chartreuse St. Sauveur, built by Carthusian monks over half a millennium ago now. Structures of Catholicism’s reign, antique and sovereign, physically, mentally. The day I arrived, come from Toulouse through town and vineyard, I was struck by how naturally the sun fell over the buildings of dun stone as I walked from the train station to the medieval center, crossing the bridge that spans the lazy, duck-mottled Aveyron. My apartment was cheap and miniscule, a garrett with slanted roof, whose two small skylights, the only windows, gave onto a foreground of lychen-decked masonry, and a background of rolling, wooded hills. What year was it? What century? No sooner had I put down my bags that I found my imagination transported to an idyllic, idealized past, one that, like Villefranche’s bewitching façades, revealed but a sliver of the place’s tale.

Half due to rural flight, half to the lore of the region, the longer I stayed in the Aveyronais city, the more a sense of hauntedness fogged down its ruelles. During my year, four of the scant few small businesses downtown were razed, either acts of arson or desperate grabs at insurance monies. More than half of the homes in the town stood doorless and abandoned, littered with the odd stained mattress and family of vagrant cats. A short drive away was Rodez, the city where Artaud endured his deranged electroshock procedures. Heroin addiction, they said, had taken hold of the region. The one decent tavern tended to close on the weekends because, it was jested in truth, business was so slow that its bartenders preferred to go off to drink in another town’s bar. Such was contemporary life. But the bastide and its environs held even deeper, more millennial pains. The dense, dark woods a mere ten minute walk from the center felt increasingly possessed by a mixture of phantasms from lived history and folklore: the revenants of miners who had lost their livelihoods to the whims of industry, of burned Cathar mystics, plague victims, and rebel soldiers executed by SS soldiers during the 2nd World War, loup-garous gone hirsute under the full moon and giants hungry for bread ground from the bones of children, the occasional medieval troubadour who had wandered, singing, out of time. A frigid breath exhaled from deep within in the deserted mines; you could feel it if you pressed your hands up to the boards nailing their mouths shut. For all this, I came to feel that if I knocked on the right — or wrong — door, the picturesque town I knew would shatter like the windows of its deserted factories, a parade of monstrosities and myth defiling from an unshielded void.

Clark Ashton Smith’s imaginary region of medieval France, Averoigne, like the Aveyron I came to know, is a Janus-faced world, whose hale Christian surface cloaks its Satanically pallid, appalling depths. His is, without question, the more severe. Smith’s Averoigne is a world where pure hatred and cursed desire roil behind every alluring smile, where discrete portals lead poor souls from a bonny France of natural wonders, scholarly monks, and rare manuscripts to scathing infernos where, for example, a scorned dwarf can be found building, of rotten human carrion, a bloodthirsty colossus in his own image to perform atrocities upon his own community, the very narrations of which could provoke convulsions. It is disputed whether the author based his world on the historical French proved ince of Auvergne or the modern day department of Aveyron, though such nitpicking may lie beside the point: he never traveled to either, never to France at all. Smith’s Averoigne is an Aveyron of the mind. Necromancers, werewolves, vivified gargoyles, enchanted toads, witches, wandering goliards, alchemists, vampires, sorcerers, possessed monks, scholars, satyrs, dwarves, and enchantresses: these are the sorts of characters you will meet among Averoigne’s ensorcelled groves, in the halls of its time-racked chateaux and monasteries. And so Averoigne is a book that, like its own lamias, begs us to join its flight to a beautiful land that could only devour our souls, leaving us stranded there, somehow contented to bask forever in its beautiful Hell.

But while this world is formed through the borrowing and distortion of character and setting tropes from the French medieval imaginary, it is also Smith’s linguistic dream of a medieval French realm of the English tongue itself, a Shangri-La of his notorious etymological play. A great many scholars and editors have expressed their fatigue over Smith’s Francophilic, “purple” prose — such as the those at Weird Tales itself, whose tonings-down he grudgingly obliged, being in need of funds to support himself and his aging parents. And yet to witness the author apply rarity after etymologically-precise rarity to a meet recipient is among the most fascinating parts of his work. Even his choicest words do not read as belabored sesquipedalian thesaurusisms to me, for no thesaurus contains such breadth of vocabulary. Rather, these are lived, known, and studied terms, applied with rigour to impact his readers in a definite, premeditated way. Smith himself noted this, writing in a letter:

As to my own employment of an ornate style, using many words of classic origin and exotic color, I can only say that it is designed to produce effects of language and rhythm which could not possibly be achieved by a vocabulary restricted to what is known as ‘basic English.’ (…) An atmosphere of remoteness, vastness, mystery, and exoticism is more naturally evoked by a style with an admixture of Latinity, lending itself to more varied and sonorous rhythms, as well as to subtler shades, tints, and nuances of meaning.[1]

His linguistic supersaturation is a controversial, yet confident, choice, one which demands the trust and devotion of his readers, for its flight in the face of prim literary convention. Why should everyone write with moderation? And what good is terse prose to the ones who wish to macrodose on language? We need some radicals, and Clark Ashton Smith is among the few etymological radicals English has. By his immoderate formulæ, Smith’s Averoigne tales are piebald with atmospheric synonyms and unusual doublets of more common words, rarely used sub-definitions, as well as precise terms derived from Latin long gone out of use. Among the synonyms used for tonal effect, we find quondam standing in for former, subterrene for underground, vans for wings, hautboy for oboe, and cachinnations for booming laughter; but we also find words of deep singularity like invultuation, which denotes the act of making images of humans and animals for witchcraft, enormity, stripped here of its general sense and employed to describe a particularly heinous crime or sin, and catafalque, a raised structure whereon the body of the dead rests or is borne in state.

Throughout his work, the far-reaching roots of Smith’s vocabulary reveal an even deeper attention which exceeds the Latinate, encompassing words from every wing of our tongue, and making his stories a living museum of the English language. A word such as meet surprisingly springs up as an adjective derived from Old English, in which form it means suitable or fit. Suddenly the word sate is deployed not as a verb meaning quench, but as the obsolete past tense of the verb to sit. His sentences ring Arabic when he describes specialized alchemical rigs, naming such tools as the aludel or the athanor. Objects of a bright orange-red tint are occasionally deemed nacarat, an adjective derived from Spanish and Portuguese’s nacarado, signifying pearly or nacreous. Old English explains his use of a word so rare as emmet to name a creature so common as the ant. A deeply Smithian adjective, Eldritch, meaning ghostly and sinister, derives from Scots, perhaps kindred to elf. And the heavens are referred to not with the flavorless sky, but with the pungent West Germanic welkin, while the Dutch-derived minikin appears where he might well have used small. And what may be the most Smithian noun of all, eidolon, a phantom or apparition, is a direct borrowing of Greek’s own εἴδωλον [eidolon], a long-slumbering, seldomly roused term for ghost drawn from Classical literature. And what were the Middle Ages, if not a moment when these languages and their offshoots began to mix more intimately? Though it depicts France, Averoigne is ultimately a profoundly English-language work, in that its atmosphere, its exercise in exploring, even translating, a portion of the French imagination depends on the English vocabulary’s peculiar contents and past.

Smith’s own French, like his Spanish, was self-taught, the product of and tool for his famously autodidactic study, rarely, if ever, strengthened by the chance to speak it. Instead, the West Coast Romantic exercised his francophilia through reading, writing, and translation, an art in which the raconteur, poet, sculptor and painter excelled, though for which he is much lesser known. Among his sumptuous translations from the French—recently made available for the first time in a volume edited by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz, and published by Hippocampus Press—we find works of the great French Romantics and Decadents: all but a few of Baudelaire’s verses from Les Fleurs du mal, and poems by Théophile Gautier, Paul Verlaine, and the kindredly hallucinogenic Gérard de Nerval. Now on the subject of translation, I admit that, as a translator myself, I have turned to Smith for guidance in tone and turn of phrase while translating the French Symbolist Marcel Schwob, another great metteur-en-scène of carefully-worded medieval dramas. I imagine these tales to be Smith’s chance to travel, not only through France — from the great Northern city of Tours down to the Southern expanse of the Aveyron — but through time, as well, from the tedious evidence of contemporary life to inaccessible, lofty centuries wrought of improbable dream and adventure.

I think back on the intoxicating woods of the Aveyron Valley, wondering if perhaps I could have found those troubadours, those giants, those loup-garous, had I only stumbled on the right—or wrong—door. At the same time, I feel naive to have trafficked in such phantasmagorias, when the world around me was in acute material distress. And yet such is how the imagination works at times, that raw and mercurial companion, who speaks in spite of urgent fact and tugs at our hems to leave behind the inherited Earth before us. Is this a pang Smith felt as well? No other world among his writings feels so bound to actual human endeavors, to the concrete ruins of landscape and lore, to humanity groping toward a sense of itself. What his Averoigne offers us is an affective history, a surrender of the imagination not to history’s facts, but to its ambiance, its desires.

[1] (Selected Letters of Clark Ashton Smith, 365. Referred there by Darrell Schweitzer’s review of The Complete Poetry and Translations of Clark Ashton Smith.)