“Myself alone! I know the feelings of my heart, and I know men. I am not made like any of those I have seen; I venture to believe that I am not made like any of those who are in existence.” A sentiment, while couched less ornately, that would not be out of place in Donald Trump’s magnum opus, The Art of the Deal.

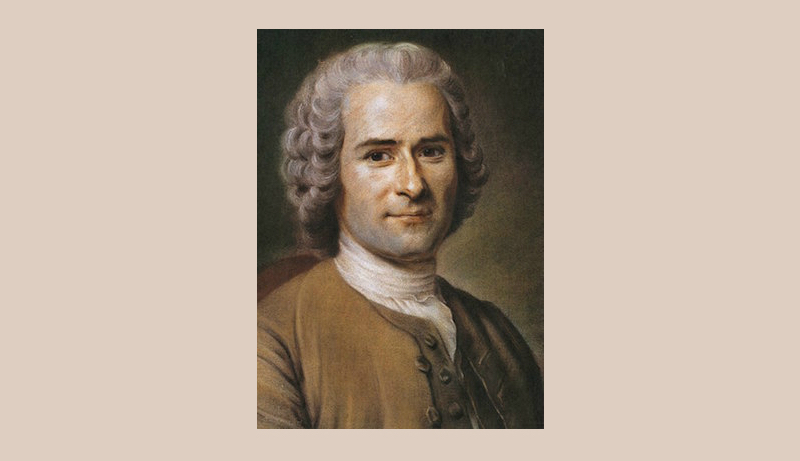

But when one continues the quotation — “If I am not better, at least I am different” — the Trump brand evaporates. Instead, these words issue from an earlier bestseller: The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Next year will mark the 250th anniversary of a work you perhaps have heard of and probably have not read. But it is a work that has not only made your world what it is, but also made the man who currently presides over its destiny.

The autobiographies of the itinerant Genevan philosopher and aberrant Queens developer are, for the most part, utterly different. One was written by a deeply reflective and widely read thinker, the other ghostwritten on behalf of a wildly reflexive and scarcely literate doer. One work reveals the author’s faults — “Let the readers groan at my unworthiness, let them blush at my wretchedness” — while the other work revels in them: “The point is you can’t be too greedy.”

But the two works share one crucial trait so deep as to be a kind of cultural DNA: the belief in the primacy of authenticity. In The Confessions, Rousseau warned that, at times, he got facts wrong. But that hardly mattered: his internal feelings, not external facts, were his guide. “I cannot go wrong about what I have felt.” This early critic of reality-based communities thus anticipated Trump’s advice to “listen to your gut, no matter how good something sounds on paper” and to embrace “truthful hyperbole.”

Rousseau thus insists only he can measure the accuracy of his self-portrait. The scales that weigh the truth are buried deep inside him, and only he, Jean-Jacques, can see them — or, for that matter, tilt them with his thumb. This is the only truth — even though it is an “alternative truth” — that matters. Were The Confessions published today, it might well be titled The Art of How I Feel.

As the literary critic Lionel Trilling noted, Rousseau’s advocacy of authenticity marked the end of sincerity. The value of sincerity, Trilling argued, entails the moral obligation of being true not just to our selves, but also to others; the duty to be not just who we are, but who we ought to be. While Rousseau never claimed that sincerity was for les perdants, or losers, he believed that authenticity had made him a winner. Not because he behaved better than others, but because he was willing to confess that he behaved as badly.

As countless polls in 2106 reminded us, this trait was Trump’s ace in what The Week called the “authenticity sweepstakes.” Unlike establishment politicians from either party, Trump was unpackaged and unrehearsed, upfront and upending. Whether you liked it or not, what you saw (and heard) was what you got. As Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert (and Trump supporter), declared: “He is always full-Trump and never anything else.” Enough voters liked this kind of authenticity to place its owner in the White House. One year later, as his base fissures, what passes for his authenticity nevertheless remains Trump¹s strongest suit.

Not all kinds of authenticity, however, are equal. Rousseau believed that, upon burrowing as deep as we can into ourselves, we discover we are good. By recovering our authentic selves, we rediscover our original goodness — a state of being that had been defaced and despoiled by society. In what became a clarion call in the Age of Romanticism, Rousseau declared that everything is good when it comes from the Maker of things, yet everything degenerates in the hands of man. No less important, Rousseau gave great effort and showed much art in his apparently effortless and artless depiction of authenticity. This contradiction — namely that every effort to express our authenticity through language is, by definition, a work of artifice — was one Rousseau happily accepted.

All of this has changed in the Age of Trumpism. Rather than channeling, as Rousseau believed, our essential goodness, authenticity now taps into what is believed to be our essential selfishness. Rather than everything being good in its original state, the only good is to believe that everything has always been, and will always be bad. No less troubling is the changed attitude towards language. Whereas Rousseau turned to a vast array of rhetorical tricks to warn his readers against rhetoric, Trump’s impoverished language is, to his supporters, proof against his fakeness.

In the end, Rousseau refused to be embarrassed by his paradoxes. They are the fruit, he explained, of reflection. For this reason, and perhaps with a nod to Trumpian authenticity, he concluded: “I prefer being a man of paradoxes than a man of prejudices.”