Although it is not a desirable practice to purchase food at local markets, the fruit is excellent, particularly apples, pears, peaches, and persimmons. The practice of appropriate sanitary precautions enable the safe consumption of these items.

— Guidelines for visiting physicians in Korea, 1957

“Are you Chinese or Japanese?” This is what my high school chemistry teacher asked me, having sidled up to my lab station. This was in the 1980s in a small, all-white town in northern Minnesota where everyone knew everyone; I realized he must just think of our family as the odd nonwhite family, not all-American, but from the amorphous glob of land <sound of a gong> called Asia. The Orient.

By the squinty look in his eye, it was clear his intentions were not good. “I asked you if you were Chinese or Japanese!” he boomed, ensuring every head turned toward us. Bullies always called me chink or jap, never gook. Similarly for my teacher, my Korean descent exceeded his imagination and geographical knowledge.

Having been raised to always respect authority, especially teachers, I reluctantly revealed: “Korean.”

“Oh-ho!” he said, theatrically, again making sure all the other students in the lab were looking at us before he delivered his punchline, a real knee-slapper: “You Koreans wok your dogs!”

He guffawed, bent over with hilarity. I remember my lab partner staring at me as if I’d just unleashed a dormant typhoid virus into the room. But I don’t remember how the rest of my classmates reacted, if they did. All I know is I kept staring at the emergency shower, wishing I could pull the chain, dissolve, and escape through the drain.

This incident appeared as a pivotal scene in my first published novel, Finding my Voice. There’s an entire generation of now-college students who want to talk to me about that scene, how they had their own versions of “Wok your dogs!” Dear Mr. Carlson, the chemistry teacher, has passed, but this incident is still, “indelible in the hippocampus,” as they say, three decades years later. It haunts me because versions of that squint still appear in front of me, an academic and author, when meeting new people — as if they’ll expect me to smell bad, or, there will be a preemptive “What?” signifying they can’t understand my English — before I’ve even said a word. Despite my US passport and birth certificate, in American culture I’m steeped in a kind of foreignness that no amount of enunciation, cleanliness — or time — can allay.

This is why the announcement of a new “clean” Chinese restaurant in New York’s swank Greenwich Village, owned by a white woman, dips into that racist current of dirty invasive Asians — and we all felt that jerk of electricity. The restaurant is named Lucky Lee’s (obligatory chopstick-inspired font) because the owner’s husband’s name is Lee (thankfully she did not marry a Melvin or Jared or Troy), which, some critics contend, misleadingly suggests an Asian is involved. What is not in dispute is the white woman owner publicly claiming that her food is better because regular Chinese food by regular Chinese chefs makes her and her ilk feel “bloated and icky.”

Lucky Lee’s food is presented as containing no sugar, gluten or dairy, although Chinese food is naturally dairy free; yet, she puzzlingly also derided Chinese food by Chinese as swimming in “globs of processed butter.” Even if traditional Chinese food featured butter, which it doesn’t (dairy is absent in most East Asian cultures), what’s with the icky “globs”? With French food, copious butter is considered sensuous, luxurious, clean and white.

Local Asian American reporters went to the restaurant and reported that the rice, the bedrock of Asian cuisine, “was remarkably bad, simultaneously under-cooked and over-congealed into a gruel that I imagine even Oliver Twist would reject” which probably could and should disqualify it from being classified as a Chinese restaurant at all.

Also, naturally: a wok pun — Wok in, Take out — is displayed on their jade and bamboo decorated walls and in the window. And the lo mein is called “Hi lo-mein.” Ho ho ho.

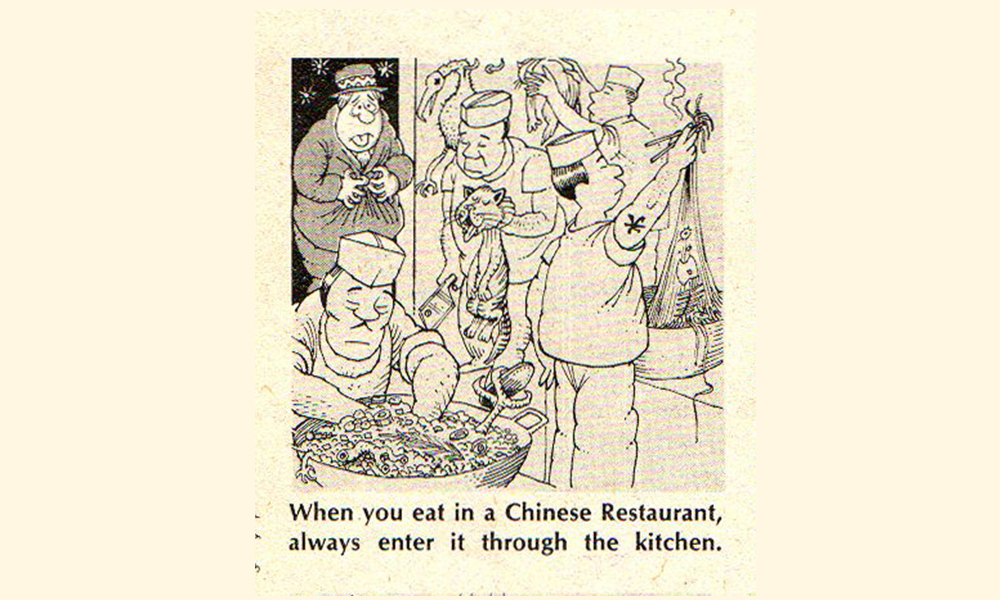

I have celiac disease and have to avoid gluten for medical reasons and understand clean eating in the wellness blogger-Gwyneth Paltrow GOOPian sense, but that does not make “clean” Chinese food an innocent communication mix-up. It uses a corporate-contemporary word to reach deep into sub rosa racism, a wok-your-dog whistle. In a white supremacist worldview, heathen Chinese and other Asians are far down the rung of cleanliness. It was my heartbreak as a child when even my beloved MAD magazine, its humor one of my solaces growing up in our tiny isolated town, wherein an otherwise funny sketch on “Cheap Revolutionary Way to Eat Out and Lose Weight!” featured a slant-eyed person carrying a cat with its eyes Xed out in one hand and a cleaver in the other. The caption: “When you eat at a Chinese restaurant, always enter through the kitchen.”

There is a Korean restaurant near where I work, and I have tried and failed to like it. Korean food is the most delicious food on the planet: subtly sweet, salty, spicy, full of vegetables, piping hot or icy cold. But this food always tastes off — too sweet, not spicy enough, an odd aftertaste of fish that shouldn’t be there. They do enough business to have survived the cutthroat Manhattan real estate market for at least twenty years. But it is because, I suspect, they’ve turned out beloved funky Korean food into a gloppy mess to cater to white tastes, exactly how Chinese food was bastardized into sweet General Tso’s chicken, the fried cream cheese wontons of crab rangoon, sugary and gluteny fortune cookies — all American inventions criticized by the oblivious Lucky Lee’s restaurateur. If anything, by removing the sugar and fry oil, she is taking Chinese food closer to its origins without knowing what Chinese cuisine actually is. We can say for certain that it is definitely cleaner than what white diners have been trained to eat.

I grew up consuming Midwestern hot-dishes. When a dusty “Oriental foods” store opened in St. Paul in the late 1970s, we kids would look on in fascination and horror at the dusty jars with Korean characters on the labels, the flattened squids, the jars of fiery red kimchi. My parents would furtively buy some seaweed, which my mother would figure out how to oil and roast on electric coil of our range. We accepted it because it was, well, tasty. But we were warned not to touch the tiny jar of kimchi, wrapped in plastic in the back of our refrigerator, sometimes fizzing ominously like the fuse of a bomb. Once, on one of those interminable trips back from Minneapolis, the jar did explode, and we were trapped in our station wagon and the smell for hours. I would not eat such a thing any more than I’d try belladonna.

I moved to New York after college and acquired some Korean friends who introduced me to all sorts of briny, spicy, mysterious foods beyond the easily-lovable barbecue. Right now in my refrigerator I have three kinds of kimchi: traditional cabbage, mustard greens, perilla leaf — all made by a Korean lady at the farmer’s market. Sometimes I feel sad that my colonized mind and taste buds meant that I’d missed years of loving Korean food. In the late 1990s I lived in Seoul for a year as a Fulbright fellow, and enjoyed a glorious year of food. When my mother was visiting, a friend, Okju, took us to her lakeside cabin. She had an interest in healthy food and therefore had a gorgeous garden. A bunch of the plants were covered in layers of spider webs. She saw me looking and clearly thinking — bugs! — and said, gently, “I don’t use pesticides. The presence of the spiders and all these insects are good. It means our food is very clean.”

It struck me, suddenly, that I thought of “clean” food as free of dirt or insects or any trace of actual nature, because that’s how it’s portrayed in ads and on TV in America, where produce has to be shiny and symmetrical. She had me harvest a bunch of dal-lae, a kind of allium, as well as digging underneath the pretty purple bellflowers to get at their pale roots, and I was covered in dirt. Together, we made a quick kimchi that had a pure taste I could describe, without affectation, as “clean.”

Asian Americans are right to object to the weaponizing of the word “clean” as a way to suggest that Asian food is only safe when white people are in charge. Arielle Haspel (and her husband Lee) should just be more honest with her marketing and say what her food actually is: “gluten-free, dairy-free Chinese-inspired food with white-people style rice.” Maybe I’d even eat there, then, because I’d know what I was getting.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee’s next novel, The Evening Hero, is forthcoming in 2020 with Simon & Schuster. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, The Atlantic, The New York Times Book Review, The Paris Review, and others.