In today’s political climate, it seems inevitable that the unfortunate can — and will — happen: every day, some fresh horror makes headlines. Trump, in his short time in office, has threatened public school systems, the Affordable Care Act, our already tenuous relationships with other countries. And, worst of all, there is nothing that us innocent civilians can do about it — no matter how unfair it seems.

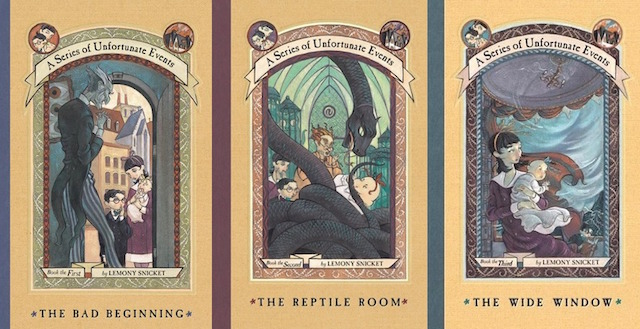

The same rules hold true in Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events. In this early 2000s children’s book series — and as of January 2017, the Netflix series starring Neil Patrick Harris — the three Baudelaire children have it all — until, one day, their house mysteriously burns down, books and parents and all. They are promptly shuttled to their distant relative, Count Olaf, a greedy actor who makes it abundantly clear that he is out to steal their fortune. He is self-reflexively the villain: he verbally abuses the children and laughs manically while doing it. Yet, while the audience hates him and everything he stands for, he knows how to work the system. He knows how to charm the other adults in the Baudelaires’ lives.

There are some uncomfortable resemblances between the gothic children’s books and America today. Below are a few eerie parallels, and some suggestions for how we can use the books to get ourselves out of our own series of unfortunate events.

Count Olaf v. Donald Trump

They are both liars.

Donald Trump made his “political” name based on a bald-faced lie, that Barack Obama was born in Kenya. He then rode this lying wave right through the campaign: PolitiFact reports that during the campaign, a full 70 percent of his statements were false, 11 percent were mostly true, and four percent were completely true. Then, there were statements on which he has totally reneged: for example, in the days after the election, he stated that he, in fact, likes the Clintons and has no interest in putting Hillary in jail.

Count Olaf’s stats would probably be pretty similar. Olaf is probably most honest when he’s alone with the Baudelaires: that he will drop the baby out the window, that he will make Violet marry him to gain the fortune, that he knows that they know that he is Count Olaf when he is in disguise. I would imagine that these self-reflexively evil conversations are similar to the ones Trump has with Jeff Sessions or Vladimir Putin. Heck, maybe even when he’s alone with Barack Obama: “Yes, Barack, I have no experience and I am going to screw this country over, but for now let’s awkwardly shake hands for the cameras.”

At the end of each episode, Olaf makes his lies clear to the other adults who blindly trusted him. In the end of The Bad Beginning, Justice Strauss says, “You are a disgusting and vile man”—then Olaf smiles and adds,, “A disgusting and vile man who has compete control of the Baudelaires’ fortune.” Trump responds to criticism with similar statements — something along the lines of, “Yeah, but I’m still the President and you’re not, ” which seems to be his favorite argument.

Then, there are the the half-truths and reneged statements. For example, in The Bad Beginning, he writes on their to-do list to “make dinner,” but after they make him pasta puttanesca, he complains that he told them to make roast beef. There’s written proof that he said no such thing, but he forges ahead. He knows that he is powerful enough for his cronies to believe his half-truth. Donald plays just as fast and loose with half-truths. When accused of assaulting women, he lists the women he hasn’t assaulted, and has Kellyanne Conway say that that he has always been a gentleman to him. Sorry, just saying something tangentially related when there’s written proof doesn’t make it true. His ongoing war with news sources like the New York Times also provide written proof of his lies: he tweeted, “The @nytimes states today that DJT believes ‘more countries should acquire nuclear weapons.’ How dishonest are they. I never said this!” yet you can read a transcript of his interview in the New York Times that quotes him as saying that it wouldn’t be so bad if countries like South Korea and Japan were to develop their own nuclear weapons.

They are both actors.

Before he met the Baudelaires, Count Olaf reportedly made his career as a low-level actor, complete with a low-level acting troupe who act as his villainous cronies once the Baudelaire chase begins. In The Bad Beginning, Olaf creates a “play,” The Marvelous Marriage, to disguise the fact that he is actually marrying Violet for her money. Then, in the following escapades, he quite literally dons elaborate disguises to fit into their new guardian’s world. But he is only and actor, and this gets him in trouble. In The Reptile Room, he pretends to be their Uncle Monty’s assistant, yet he clearly knows nothing of reptiles. In fact, he doesn’t get away with killing Uncle Monty because he frames The Incredibly Deadly Viper as the murderer, when it is, in fact, the friendliest snake on the planet. His lies would have worked if he had just known the tricks of his pretend trade.

Trump’s attempts to act like a President have been similarly laughable. First and foremost, Donald too started his Presidential journey as a low-level entertainer (Did anyone say, “You’re fired”?). And we know he loves disguises — the very icon of his campaign was a red baseball hat, for goodness sakes. Whenever the man visits a construction site, he simply has to don a hardhat to exude constructional authority, even though he surely is not crossing paths with any sort of constructional danger during the visit. Looking the part means being the part to Donald. But these disguises aren’t so convincing. They’re shoddy, makeshift: for example, when the wind blew on Inauguration Day, the back of his tie showed scores of scotch tape holding it together—an apt metaphor for his persona. He is nothing but a scotch-taped-together lookalike of a President.

Most importantly, this playacting is dangerous. Sure, let Donald pretend he’s driving a big rig on the White House lawn, but imagine him behind the wheel on a busy highway. Suddenly the metaphor seems a lot more dangerous.

Adults Blindly Believe Him

This is tied up with the theatrics: Olaf and Trump’s disguises are so convincing, and their lies so specific and bombastic, that people believe them because they are in the position of “expert.” Trump’ alarmist statements evoke emotional responses. At a rally, he announced that “the murder rate is the highest it’s been in 47 years!” It’s so specific that it seems true. And he would know, since he’s President, right? The other adults believe Count Olaf, because the Incredibly Deadly Viper sounds deadly! And he works with reptiles for a living, so of course he would know. Both play with emotions and their position of power.

The Other Adults in America are the Trump supporters. They believe too much in authority figures and right-sounding statistics to question Trump’s veracity. In a way, they are complicit in his villainy, since they allow him to get away with it. But, they are not villains—they mean well, and simply have too much faith in the good of humanity. One hopes that they can be made to see the truth.

They both have weird hair.

Olaf has a unibrow, and hair that sticks out like two horns on either side. Trump has a comb-over that matches his skin color. Enough said.

Trump’s Minions v. Olaf’s Minions

Weird Old Twin Ladies

Female minions who speak in near-unison, echoing the morals of their leader. Enter, Kellyanne Conway and Ivanka Trump.

Tall Bald Brute

“Brute” here means dense and has no mind of his own. Hi, Sean Spicer!

Hook-Handed Man

A little bit of irony here because he’s ethnic and in Olaf’s troupe, but his deadly hook hands reminds me a lot of Jeff Sessions and his unwieldy control of weaponry.

Their Houses

Olaf’s abode is a beautiful mansion that, under his tenure, has fallen into frightful disrepair. At this rate, that’ll be the White House in four years.

How We are Like the Baudelaires

Violet Baudelaire is a technological wizard. The instant she ties back her hair with a ribbon, she is in inventing-mode, and can make incredible tools out of everyday objects around her. Klaus, meanwhile, is the bookworm. He can read an extraordinary amount in no time at all, analyze and synthesize what he has learned, and recall useful facts when they’re needed most. Sunny is only a few months old and can speak in gibberish, but her teeth are comparable to little razors. She is helpful in adapting objects for Violet’s inventions.

We, the non-Trump supporters, are a lot like these three orphans, who see Olaf for who he really is. So, hopefully, we can channel our inner Baudelaires to outwit him again and again. We are savvy like Violet: we, unlike Trump, are inventive and can make tools using our imagination. We have web developers, journalists, and television personalities figuring out how to change their craft to fit this new era—adapting their everyday jobs into politically subversive machines that can thwart Trump’s evil plans.

We are smart, like Klaus. We have the Internet at our fingertips, and can find Real Facts in a matter of seconds. We can use our smarts to write, argue, and publish the truth. We too can synthesize and analyze the truth to combat the alternative facts.

And, like Sunny, we are surprisingly strong.

How the Netflix Adaptation is On Our Side

While the book series is also on our side (“our” here meaning rational and kind to others), the Netflix adaptation takes it a step further. For one, they took to heart the diversity problem in Hollywood: even though the guardians in the book series (as well as in the 2003 movie with Jim Carrey) are white, the Netflix adaptation casts Mr. Poe (Ken Todd Freeman) as black, Uncle Monty (Aasif Mandvi) Indian-American, and Aunt Josephine (Alfre Woodard) also black. Subtle stands against racism like this will not change the world in themselves, but if enough TV shows do their part, the change will come.

The Netflix adaptation also amps up the importance of VFD, the underground organization of which the Baudelaires’ parents—and Olaf—were once a part. The show creates a whole new character, a member of VFD who starts as Poe’s assistant, and subsequently changes undercover positions to help the Baudelaires as they move through their adventure. Even in the face of such prevalent evil, they create a secret organization to fight it. We can do the same. This is a notable difference between the books and the series: the Baudelaires are not entirely alone. With a strong enough community, they can succeed in conquering Olaf once and for all.

The Importance of Lemony Snicket

In the books, Lemony Snicket is the fictional narrator created by author Daniel Handler. Snicket was once a part of VFD, and it is now his job to document the terribly unfortunate events that unfolded after the Baudelaires were murdered.

Even though it tells its story visually, the Netflix adaptation does not eliminate Lemony Snicket. He is a tangible narrator, a man (Patrick Warburton) who walks in and around the scenes as he tells the tale. The characters cannot see him—he is visible only to us, the audience. He, therefore, is on our side. But, he does not tell us what to do. He merely documents the events. He is like the writers and journalists of our time, who can only tell a story; no matter how much they try, they cannot control the actions of the players in the political game. It’s the same with us, the audience—we cannot help the Baudelaires from our couches.

But we can keep watching. If we watch the Baudelaires, we can learn from their tactics. We can watch the “news” in Lemony Snicket’s alternative universe and use it to help us in our real one. We can can use our ingenuity and smarts. We can create an underground organization. We can even learn from the Baudelaires’ mistakes. To paraphrase Michelle Obama: when they fail, we succeed.