When I was growing up, I spoke a language different from those around me, including the members of my own family. It was a language I learned in books.

One day, when I was nine, I was taken to the wake of my Great-Aunt Annunziata, twin sister to my grandmother Elvira on my father’s side. She lived with her sister’s family, helping her raise five sons in a two-bedroom apartment in North Newark until her death at 70. As my father, mother, and I walked together down Orange Avenue, in the shade of its towering maple trees, to Christiani Brothers Funeral Home — a name I remember due to the numerous wakes in store for me there over the next few years — I was rehearsing under my breath what I planned to say when I got there, particularly to my Uncle Sonny, who, as the youngest of Aunt Nunzi’s nephews, had been her favorite. Going up the front steps, I practiced my speech one last time, aloud, so that my parents heard it. Its verbal spirit, if not its exact words, was taken from the book I was reading at the time: David Copperfield. “I am honored, my dear uncle, to offer you my condolences in this unhappy hour.” Or something close to that. Something miserably close to it.

I don’t know why I let my parents hear me; I don’t remember whether I was seeking their approval or just fixing the elaborate sentence more firmly in my mind. My father’s reaction, though, I remember very well. He stopped and muttered a few words to my mother, which I didn’t understand, since they were in the ragged Southern Italian dialett’ they sometimes spoke together, but I could tell that they were dark and dismal words. Then he turned to me and said that when we got inside the funeral home I should just go kneel before the coffin, cross myself the way everybody else was doing, then sit down and keep my mouth shut.

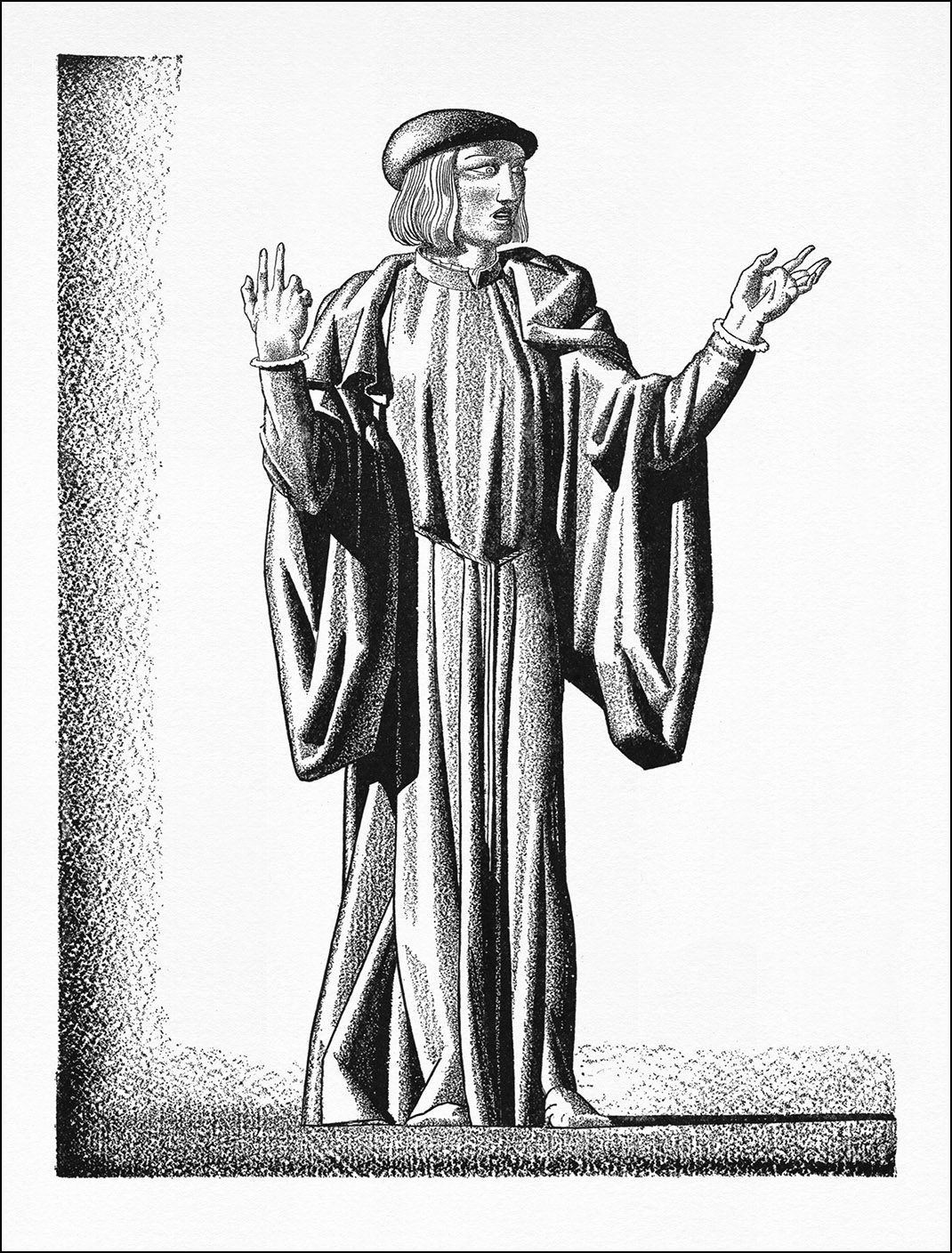

The speech I’d prepared (but never made) was not a typical example of how I expressed myself, which would vary with what I happened to be reading. My father’s reaction reminds of another time, a year or so earlier, when I waited by the door one night for him to return from work. He worked at the sheet metal factory in Bayonne, owned by my mother’s father. I waited, holding to my chest an oversized tome that weighed about two-thirds as much as I did — the complete plays of Shakespeare, illustrations by Rockwell Kent — to ask my father which of the plays was his favorite. My father’s education, as it happened, had stopped in the 8th grade.

I asked as soon as he came through the door. He stood a moment, then sat in a chair while he took off his jacket — slowly, as if he were suddenly more tired than he’d been a moment before. The look on his face was much like the one he might have had if he’d just learned I’d broken some valuable household object. Finally, he said, “I made you.” He said it in a calm tone of voice, without anger, and only a slight trace of emphasis — “I made you” — as if informing me of some obscure fact I didn’t know. That was all. Then he stood up and let my mother know that he was home.

It wasn’t so much that my parents — or uncles or aunts, neighbors or family friends — didn’t understand what I was saying; I nearly always managed to make myself understood. There were times, too, when hearing me speak amused them. Other times, though, in a way they would never let on, they were a little frightened. And nearly always, to one degree or another, put off. This was maybe because my language created a feeling that an alien presence was growing up among them. More likely, though, it was because it carried more than a whiff of self-conscious superiority.

In this they were wrong. My language, even at its most ridiculously inflated, was native to me, in one particular sense: in learning to read, I’d finally found the words to give the world the only shape and meaning it could have, at least for me. The language of books, for all its conventionalism and even artificiality, did for me just what any language, spoken by anyone, does for them. So the reaction of those around me — in particular my father, which would often mount to genuine anger — was unfair.

But it was nonetheless sincere. The feeling that your own child is “looking down” on you is not one you want to have. It’s easy to imagine that such a child is deliberately distancing himself from you — from your love — and this might even make you want to hold back your love in return. As a result I spent a lot of time being afraid of my father. I would lie in bed in the morning until I could hear that he’d finished breakfast. It wasn’t until I heard his car — a DeSoto with an oddly human-sounding cough — start up and go away, that I climbed out of bed.

My mother, too, was afraid — and not, I’m compelled to say, mainly on my account. Rather, she was afraid for herself, that my father would include her in his growing resentment, hold her responsible for my growing and unbridgeable difference. In fact there was something specific, whether he knew it or not, to justify her fear: some of the books I fawned over, so mutinously from his point of view, were leftovers from my mother’s high school days. She’d graduated. I didn’t know to what extent she’d read or remembered them, but they were hers.

There was another way she was responsible for the mounting pile of books beside and beneath my bed, though it wasn’t intentional on her part. Rather, it was an act of kindness. My mother had a brother-in-law, my uncle Hugo. He was Sicilian, dark and dour, in contrast to the noisy, affable Neapolitan brood of uncles on my father’s side. Uncle “Yoolie” had two jobs. He was a small-scale tomato farmer part of the day. He planted and tended an abandoned lot beside his house on Fifth Street and sold the crop in a curbside stall. He was also an old-fashioned junk-man: he drove around North Newark in a horse-drawn wagon, ringing a bell to summon housewives to the street, where he traded with them in used clothes, knick-knacks, pots and pans — and, when the chance presented itself, old magazines and books. He would regularly gift these to my mother. Yoolie himself was illiterate, and not just in English, which he spoke with an accent we kids imitated mercilessly. The illustrated Shakespeare was one of his gifts — a fact which did him no credit with my father, who could interpret my infamous question about which play was his favorite only as a speech-act intended to offend and humiliate him. Copperfield was another, along with a tattered photographic history of World War I, a guide to medicinal herbs, a collection of poems for reading aloud on public occasions, and Les Miserables. In addition, I remember Forever Amber, a memorial volume commemorating Vittorio Emmanuel II (late King of Italy), Two Years Before the Mast, a Brooklyn Dodgers yearbook from around 1950, several prayer books, and Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini, author, according to its cover, of Scaramouche.

Concerning Captain Blood — a huge best-seller in its time — I have another, later memory. 20 years would pass before I was reminded of its gaudy narrative and dashing hero who, with glittering eyes and sabre aloft, adorned the faded paper wrapper. Its reappearance in my life is something I can date almost exactly: it would have been the date of a lecture, given in early September, welcoming us, the entering graduate students in English and Comparative Literature, to Yale, given by an eminent historian of the French Revolution who was also a poet in his own right. It was held on the second floor of the building that housed several Humanities departments: an elaborately faux-medieval structure, like many that went up at the university in the 1930s. But it is what I came across on my way to the lecture that I want to tell you about.

Over the entrance to the building, in true Neo-Neo-Gothic style, was an arch decorated with carved beasts and gargoyles, the entwined limbs and leering faces of stone creatures that no doubt had been meaningful in 13th-century Europe but were utterly fanciful in Connecticut now. These decorations, we were told on an introductory campus tour, had been the work of carvers and stonemasons brought from France and Italy after the First World War. Unmentioned on the tour, though, was the unremarked sentence, some 16 words long, chiseled into the granite archway above our heads. Doubtless, like all such inscriptions, it was rarely read by the students who’d been passing under it for decades, and I don’t know what, other than a gawping wonder at all things new in my surroundings, made me stop to read it now. But when I did I was startled to realize I was reading the opening sentence of Sabatini’s lurid potboiler, which declared about its hero — to the sound of trumpets, one is inclined to say — “He was born with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.”

What this could possibly have been meant to signify to 20th-century graduate students — about to be engulfed for the next few years in speculative discourse on linguistics, literary history, and theory — can only be guessed at. I don’t suppose anyone in the university’s administration ever signed off on its message. Most likely it had been the impulse of a lone carver, perhaps merely mischievous, perhaps proud of its author’s Italian last name. The moment I recognized it, I nearly came out with my own version, however brief and non-heroic, of the laughter that Scaramouche allegedly bestowed on the entire world.

And then, in the following moment, I thought of Uncle Yoolie — of Uncle Yoolie, with the books he gathered for my mother piled in the junk-wagon behind him. And I thought, too, as I trudged up the forbidding grey stone stairs, of what it meant to read, and to remember, and to dream of what you read. I thought of good books and awful ones, and of the language they had bred up in me, both rich and troublesome. I joined my new classmates on the landing of the second floor, as they headed into a crowded hall to hear the lecture that was about to be delivered — the herald, whatever its proper subject, of all the lectures and the books that lay before me, and of the language that would enter into me from them, like the language of the books of my childhood, shaping me for good or ill.