During these dark and anguished days in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, I happened one morning to come across Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow’s recent message to the Harvard Community, titled “What I Believe.” A friend had forwarded it to a group chat I belong to.

Bacow’s letter was intended, I have to assume, as an uplifting message of unity and optimism. It is a strange byproduct of the idea of meritocracy in the US that we have become accustomed to expecting wisdom from bureaucratic leadership. But something compelled me to read on, and I did, in bed, on my phone, growing ever more despairing and frustrated.

What was it about Bacow’s letter that elicited this response? You might imagine from what I’ve said that his letter is rife with open racism — it’s not. Or that he doesn’t express condolences for George Floyd’s death — he does. Yet, reading the letter, one gets the unmistakable sense of the perfunctory. That although Bacow’s letter is written to the entire “Harvard Community,” the audience in his mind’s eye is one that looks and thinks like him — and he is writing about something terrible that has happened, somewhere far away, to somebody else. In fact, the narrative upon which the letter depends largely excludes the experiences of Black Americans, despite what has prompted Bacow to write the letter in the first place.

I suspect that one of the reasons I am attuned to the subtext of this letter is because I am a translator. Language and its machinations are never far from my mind. Also, I am Asian American, so the experience of being excluded from the dominant narrative, or of being expected simply to fulfill one’s given role within that narrative, are ones that I am not so unfamiliar with. And during these excruciating days of national grief and reckoning, I have found myself more acutely attuned to the sheer ubiquity of the suffocating and lethal exclusion and dehumanization, even from our country’s most vaunted or trusted institutions, perpetuated toward black men, black women, and black children.

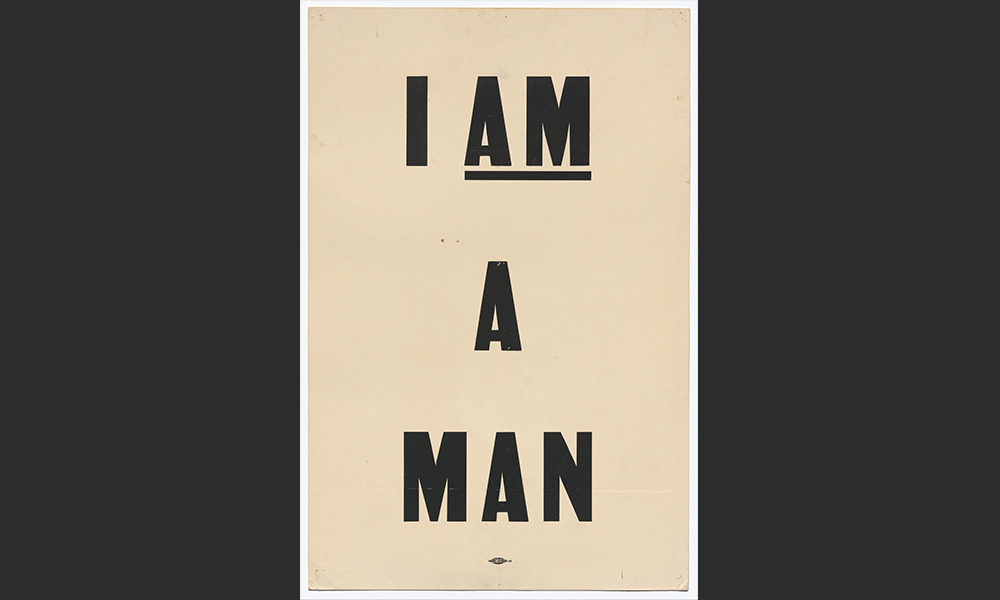

Nobody needs for me to repeat this, but for hundreds upon hundreds of years, Black Americans have persisted — at unimaginable cost — to communicate a truth so basic that it should never have necessitated utterance: the truth of their humanity. Who can encounter the photographs of black sanitation workers on strike in Memphis in 1968, bearing signs across their chests that assert I AM A MAN and not be overcome with an engulfing shame in being the person towards whom this message needs to be directed? And yet the great majority of us still live under a blindness to this natural truth, a blindness created willfully at the birth of our nation, and which still dominates our cultural narratives, instilling in us an acceptance of “whiteness” as default, and “blackness” as “other.” This blindness grips us, whether we think of ourselves as racist or not — whether we even think of ourselves as belonging to a race or not — and it has accompanied us for so long that our eyes and souls have adapted to it, and forgotten their own lack of sight.

And when it seemed that, at last, the unbearable tragedy of George Floyd’s death had stunned many of our eyes into temporary, flickering vision, had impelled us to approach the uncomfortable task of self-examination, here came this letter — from an individual to whom we have ascribed wisdom and compassion, and with whom we have entrusted authority and power — that appears to have coolly side-stepped this moral duty, serving us, instead, the same stale story.

Let me try to explain what I mean more methodically.

Bacow’s letter begins with a description of the hardships imposed by COVID-19 around the world. He names the death and destruction that have accompanied the virus, and empathizes with the “loss of jobs” and “liv[ing] in fear.” One senses the heartfelt emotion here. One senses his imagination working actively to place himself into the collective consciousness of these times, as bounded by COVID-19, especially alongside those intimately affected by it. Then, continuing to the second paragraph, Bacow addresses the “senseless killing” of George Floyd. The country is “shocked,” he writes, and yet here is where the emotional immediacy of his writing drains away. “Our cities are erupting,” he says, without saying what they are erupting with — anger, pain, frustration, anguish. “Our nation is deeply divided,” he continues, without naming what we are divided by — centuries-old systemic racism and structural inequality. He calls on us to take comfort in the example of our nation’s history, for even after 1968, a time when “hope was in short supply,” our country was able to “move forward.” But who does this retelling of history fail to include within its field of vision? Who, as the country moved forward, did it leave behind?

As Bacow’s empathetic and emotional imagination fades, his words begin to rise up the ladder of abstraction — as though, containing little feeling or substance, they are drifting off into the ether. And it is here that he commences an 11-item enumeration of “what [he] believe[s]”. To give you a sense of the content of these beliefs, one stand-alone line reads: “I believe in the American Dream.”

And another: “I believe that America should be a beacon of light to the rest of the world.”

Remove and detachment — a palpable chasm between the fortunate “us” and the unfortunate “them,” as though one side is observing the other from a distant shore — are everywhere in this well-meaning letter. In the most extreme example, while celebrating our nation’s tradition of “welcoming” immigrants, Bacow describes them as “individuals who repay us multiple times over through their hard work, creativity, and devotion to their new home.” Repay us. And who is this dominant “us” that is expecting repayment? This habit of mind, of ascertaining the value of an individual by the value that can be extracted from him or her through labor, is a product of our brutal history, and is still so ingrained in our culture, in the structure of our economics, that these words blend seamlessly with the rest of Bacow’s noble and high-sounding language. Yet one cannot begin to think about this declaration in the context of those of us who were brought here in chains, by sheer dint of a violence endlessly reduplicated through oppression. And when will they be “repaid,” one wonders.

In a more generous mood, one might be tempted to say that Bacow’s message strives toward and achieves the anodyne. One reply to the letter on Harvard’s Twitter page reads: “How many lawyers edited this?” Squinting, I can see the good intentions; its strings of platitudes exude good old-fashioned American optimism. But at what remove must one be standing to muster these words of perfunctory care — toward a recipient hardly addressed — as one’s response to this moment of crisis and collective mourning? What does it mean, at this time, to instinctively reach for the American Dream, for American Exceptionalism, and to reassert the validity of these ideals whose vacuity and failure have rarely been more crushingly evident? How does his faith remain so unshakably whole and intact?

The answer to these questions, it seemed to me, couldn’t be as simple or easy as plain old concealed racism. I don’t know Bacow personally, much less what lies in his heart, but — and you can call me naïve — surely someone who has devoted his life to higher education, who (despite being white) was appointed by Barack Obama to the board of advisors for an initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities — surely, he must care, and likely cares deeply, no? And so I sat with these questions, as the sirens wailed and sped past our windows here in Los Angeles, and the helicopters hovered, hour after hour.

Then, the next day, or the day after, I saw the video of Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine announcing that no charges would be filed against Jake Gardner, a white bar owner in Omaha, in the shooting and killing of James Scurlock, an unarmed black man participating in the protests. Kleine had determined that the killing would not be prosecuted due to “justification for use of force.”

In the video, in what appears to be a courtroom staged with three flags and a silent colleague standing behind him, Kleine, who is white, explains: “…this decision may not be popular and may cause more people to be upset. I would hope that they understand that we’re doing our job to the best of our ability and looking at the evidence and the law. And that’s all we can do… it can’t be based on emotions, it can’t be based on anger, it can’t be based on any of those things.”

I want to leave the debate over the legal judgment itself to others more well versed in this language and arena. What does seem plain to me, however, is that the process by which Kleine arrived at his judgment was compromised. As Kleine guided his audience through video footage of the shooting — an audience presumably composed mostly of press — narrating each scene with disciplined thoroughness, I recognized with a sense of alarm that what had appeared to be happening in the mind of Lawrence Bacow, as he wrote that letter, was now happening — in a far more pronounced and potentially consequential way — in the mind of Kleine. And what this was, was that blindness at work, manifesting here as an instinctive emotional sympathy with those who looked more like himself (i.e. those who were white), and a withdrawal and distancing from those who looked less like him (i.e. those who were black). To me, it is so apparent, that one can only conclude, by Kleine’s own definition, that he is unfit to be making this judgment, being, as he says, “it can’t be based on emotions.”

Kleine begins with video footage paused on a frame that shows Jake Gardner and his father standing face-to-face with James Scurlock and two companions. Jake Gardner and his father, both white, are pointed out by Kleine and described as “bar owner,” and “father,” their clothes (“plaid shirt”) and hair (“ponytail”) noted so that we the viewers can identify them, can see them in their individual humanity. James Scurlock and his friends are not identified and humanized in this way. In fact, it isn’t until the video begins playing, and James Scurlock pushes Jake Gardner during an increasingly heated interaction, that Kleine names and describes him. “That’s James, who just did that little shove there,” Kleine says. “That’s James Scurlock.” Imagine you are sitting there in the courtroom, not as a member of the press, but because James Scurlock was your son, your nephew, your brother. What does this moment feel like?

This pattern persists. When aggression is directed at James Scurlock or the others in his party, the language is detached, muted, technical. Accompanying footage of a slightly earlier moment in which Jake Gardner’s father initiates aggressive physical contact with a member of Scurlock’s party, Kleine says: “[Gardner’s father] had been… had asked people to leave, or pushed one of the young people.” Had asked or pushed? The County Attorney cannot seem to bring himself to attach an aggressive verb to the father, whom he sympathetically describes as “68 years old.” I feel for this elderly man, he is thinking, and thus invites his audience to think. And, when one of Scurlock’s party pushes Gardner’s father in return, Kleine’s language grows vivid, emotional: “…and somebody came in and knocked him back about 10 feet, you’ll see him fly through the air and end up on the ground.”

And again, setting up an upcoming clip, Kleine says: “The owner comes up to tell people to move on, and ‘Who did that?’, ‘Who pushed my dad?’” Kleine is stepping right into Jake Gardner’s shoes as he delivers those questions in the voice of Gardner, and these questions render an image of the bar owner’s hurt and innocence. These questions, if they are in fact asked by Gardner, are not audible in the muffled, expletive-laden exchange.

Finally, while addressing the fatal scene of James Scurlock’s death, the County Attorney, again, shies away from attributing direct action to Jake Gardner, this time to a degree that borders on the absurd, as though gunshots were released by an invisible, neutral hand. “That’s when [Jake Gardner] gets tackled and knocked down. There’s a shot fired there, another shot, and that gets the people off of him.” (The people he is referring to here are bystanders who have joined the altercation after hearing that Jake Gardner is armed.) Kleine continues, “Then James Scurlock comes and dives on top of him, maintains a chokehold around his neck. And this goes on for seconds. A few seconds, some time period. And then he fires a shot, and that’s the shot that killed James Scurlock. Like I said, it was one gunshot wound to the clavicle, and that was the cause of death of Mr. Spurlock — Scurlock. I’m sorry.”

Earlier, Kleine’s sympathy moves him to add that the bar owner’s father, the man pushed to the ground, is 68 years old. But, here, he is not similarly moved to say that James Scurlock, the man shot and killed, was 22.

And so, during these dark days, I have found myself grappling with the words of Lawrence Bacow and Don Kleine, not for a purpose so narrow or morally presumptuous as to suggest two more individuals to add to some list of condemned racists, but rather to imagine what it might mean, difficult as it may be, if we allow Bacow and Kleine the benefit of the doubt, if we accept that Bacow’s words of unity and optimism are sincere, if we choose to trust that Kleine’s intentions are to serve justice, justly, on behalf of his entire county, and yet — and yet the full and gorgeous humanity of the “other” is still so hard to see. I can only return, again, to the taint in the water that all of us are swimming in, and to point out its mark on us, even those of us who have imagined ourselves to be devoted to serving others, to justice and righteousness.

So where does this leave us? Good intentions are well and fine, but they are not enough to overcome the centuries-old denial of the humanity of Black Americans. We must protest, we must demand legislative reform, we must listen and read and educate and donate — but even these actions, I fear, are not enough. They are inadequate to the enormity and poisonous reach of this blindness. There is not enough paper in the world for us to legislate away the profound consequences and injustices of our shared blindness. Nor is it enough for us to learn what to say in order not to offend, or even to learn who or what to vote for. The crucial work, the transformative work, must also be happening on the level of the individual soul. As Van Jones urged the American public last week, we must engage in a “personal and spiritual accounting that all of us are now called to.” It is the work of learning to see, which includes seeing how our place in the world influences the narratives we believe, and how the narratives we believe, in turn, shape the world. This work is all the more urgent, of course, for those in positions of power — for someone at the helm of the most symbolically prestigious educational institution in our country, for someone presiding over the fates and freedom of others. The heart-wrenching tragedy of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, on top of countless others over the centuries, has finally (and once again) jolted our nation into closer relation with reality, into flickering vision. We have come face to face with our own image, and we must not look away.

One day this week, while I was thinking on these questions, I put on an episode of the radio show The Breakfast Club as I washed the dishes. It was a recent interview, and the guest was Rush Limbaugh. It was 20-some minutes marked by emotional intensity, of unexpected common ground forking into complete divergence, and then, near the end, Charlamagne Tha God challenges Limbaugh on something he had said about Obama during the Ferguson protests: “I think what you said about Obama in 2014 applies, when you said, ‘If he wants to, he can inspire,’ and I think that’s called for in this situation… But I don’t think [Trump] wants to inspire, I think he wants to incite.”

And to this, in an astonishing display of selective sight and sympathy at work, Limbaugh — who minutes earlier had asked with genuine bafflement what could be done so that Black Americans are not “angry all the time” — replies, with a softer quality in his voice: “Well, okay… I do agree with you about the inspiration… Look, the guy has had everybody and their uncle telling lies and falsehoods about him for three-and-a-half, four years now, and” — just imagine how that must feel — “he’s probably a little fed up with it.”

* Days after announcing his decision not to bring charges in the shooting and death of James Scurlock, Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine has petitioned for a grand jury to review the case.

Top image: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Arthur J. “Bud” Schmidt.