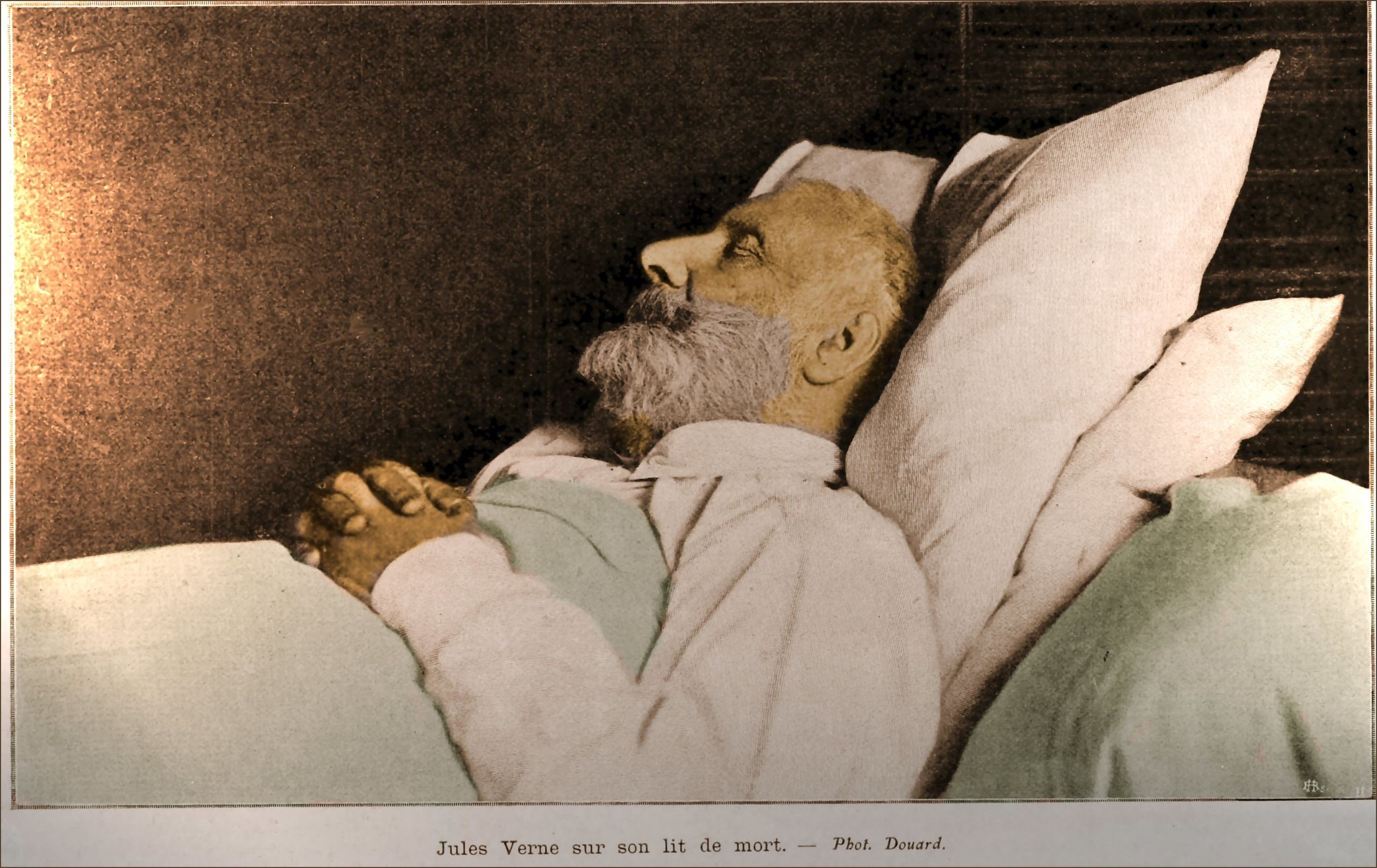

Jules Verne, who can be said to have imagined, if not invented, the 20th century, was born on February 8, 1828 — 192 years ago today. He died at age 77 in Amiens, France, of complications from diabetes.

Or we might say: died for the first time. Because his work lives on, and has not yet succumbed.

Captain Nemo, perhaps Verne’s greatest and most enduring figure, first died on June 2, 1868, at the end of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea when his submarine, the Nautilus, was spiraled to the bottom of the sea by a catastrophic and devastating maelstrom, sinking it — perhaps forever — beneath the waves.

Yet Verne’s Nemo has had more than one demise. In a later novel, The Mysterious Island, Nemo is among us once more, and dies once more. On his deathbed in this subsequent novel we learn that after the sinking of the Nautilus both submarine and captain were somehow resurrected, making port on Lincoln Island. Nemo’s second death occurs on October 15, 1868.

We learn little of Nemo’s murderous motivations in Twenty Thousand Leagues; they’re rendered a bit more legibly in Mysterious Island. But what we know depends on where we live.

In England and America — American editions of Verne followed the initial UK translations — Nemo’s pre-Nautilus life was cleansed, its details bowdlerized, its politics gutted. In the Anglophone version, the one you are likely to have read as a child, we learn that Nemo was born Prince Dakkar of Bundelkund, India — a land that the British had benevolently “brought… out of a state of anarchy and constant warfare and misery”; that a few ambitious and unscrupulous princes had in 1857 fomented a revolt, one in which our Dakkar was somehow swept up; that, when the revolt ended, Dakkar disappeared, to live out the rest of his days undersea.

What readers of French, or of the more recent unabridged translations know, is that Nemo was less a victim of that revolt than an enthusiastic participant in it, as successful a general as he had been a prince. And that the British, in savage retaliation, killed his wife and children. Hence: Nemo’s rebellion was far more conscious and purposeful, his flight far more motivated. The ships that in Twenty Thousand Leagues we learn that Nemo attacked and sunk are now contextualized: these are acts of unimaginable grief, legible revenge.

192 years after Nemo’s deaths, 115 years after the death of his creator, the story of Nemo still speaks to us. His unfathomable misery drove him to unfathomed depths. And his destructions of the Governor-Higginson of the Calcutta and Burnach Steam Navigation Company, the Cristobal-Colon of the West India and Pacific Steam Navigation Company, the Shannon of the Royal Mail, now seem less like random acts than strands in a skein of retaliation, transporting the merchant ships of empire to a depth equivalent to that of his own despair.

Even the name embodies these contradictions: Nemo is Latin for “no one,” and also Greek (νέμω) for “I give what is due.” Alienation or vengeance, depending on which classical language should be given precedence. And it’s precisely the ambiguity or, perhaps, complexity of Nemo’s agenda that causes Verne’s figure to echo, from the 19th century to our own, down the corridors of time.

In the current era Nemo appears as caricature in the Disney mash-up crossover series Once Upon a Time, his universe merged with that of Captain Hook. He’s an essential component of Alan Moore’s masterful League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, his elegance, science, violence rendered fully intact in a way one suspects that Verne would have applauded. And of course: he’s lent his name to the world’s most famous animated clownfish. These are the three contemporary faces of Nemo. Reduced to icon. Deeply understood. And as the one thing that Nemo never was: lovable.

The original Nemo was far more Old Testament that that. The murderous acts of Verne’s captain are simultaneously well-lit and obscure, political and personal: precisely calculated yet wildly arbitrary. Is this not the essence of our own age, in which the hideous protagonists who leap out at us from our news feeds are at one and the same time overdetermined and incomprehensible?

We separate parents from children at our border as a deliberate strategy of deterrence, but also savoring the cruelty. Our most brutal leaders see themselves as victims. And of course: the barbarous efforts of the Honourable East India Company to keep those of darker skin snapped to the colonial grid — as chronicled by Verne, at least in the original French — find sickening parallel in today’s Christchurch, in today’s Yemen, in other outposts of our allegedly postcolonial era. In all of these ways, the darker side of Twenty Thousand Leagues never died at all.

There is a difference, though, and it’s a crucial one: Captain Nemo was a man of great intellect and, at times, great heart. He knows who he is. One can empathize (even as one acknowledges his crimes). It is hard if not impossible to muster a parallel empathy for today’s captains of empire, who lack intellect, heart, or indeed any humanizing shred of self-awareness. In history’s long arc, these men will be given what is due. Even as Nemo dies again, lives again, as called upon by each new era — even as his creator, Jules Verne, age 192, dreams on in his eternal slumber.

Howard A. Rodman, past president of the Writers Guild of America West, wrote The Great Eastern (Melville House Books), in which Nemo’s second death is assumed to be as provisional as his first.