SPOILERS AHEAD FOR ALL SORTS OF STUFF…

Dear Television,

THIS WEEK, AHP and I will be talking about the virtues and drawbacks of sticking with series that go off the rails. Loosely, I’ll be advocating the position of The Stayer, while AHP will advocate that of The Ditcher tomorrow. But first, a memory:

I will always remember the night that I saw M. Night Shymalan’s The Village at the Hampshire Mall Cinemark. If you haven’t seen this film, it tells the tale of a small, self-governing, utopian community in Olden Times that exists in a kind of negotiated peace with some cloaked monsters who roam the woods at the edges of their town. There’s a virtuous young blind girl (Bryce Dallas Howard), a nefarious mentally-disabled man (Adrien Brody, apparently unaware that he was playing a radically offensive caricature), a puritanical/warm-hearted leader (William Hurt), and Joaquin Phoenix. When a crisis occurs, they have to come to grips, not only with the beasties that stalk in their forests, but with the world outside of their commune.

It’s horrible. The dialogue is preposterously stilted — florid, unrealistic 19th-centuryisms abound, with nary a contraction to be heard. The rituals of the village are goofy. The whole movie is thinly characterized, untextured historical fiction. It all feels like the 19th century made up by a delusional egomaniac. But that’s the trick. The big Shymalan whammy at the end reveals that the reason everyone speaks in stilted, affected old-timey speak is that the film is not set in Olden Times. The village in The Village feels like the 19th century made up by a delusional egomaniac because that’s, within the narrative of the film, what it is. The town exists in a huge, walled-in nature preserve in the present day, and the town’s elders — for some nonsense reason about urban crime in Philadelphia — have raised their innocent children in a giant Live-Action Role-Play environment. And so the weird hiccups that give the film all the credibility of a half-baked Renaissance Faire are actually a part of the texture of the film’s reality. The movie, in other words, is terrible on purpose.

And I loved it. I had to wake my friend up to explain — she was less thrilled — but I walked out of that theater feeling the perverse, perhaps masochistic, thrill that I’d been taken for a ride. The intentionality of that film’s hackishness was exhilarating to me. This director had dared to sacrifice his film to its final, shocking plot contrivance. I’ll not be putting The Village in any top ten lists or stumping for its aesthetic, but, as a pure movie-going experience, it was a rare pleasure. M. Night Shyamalan had made a silly decision, but he was in control of it, and that confidence translated right into my seat.

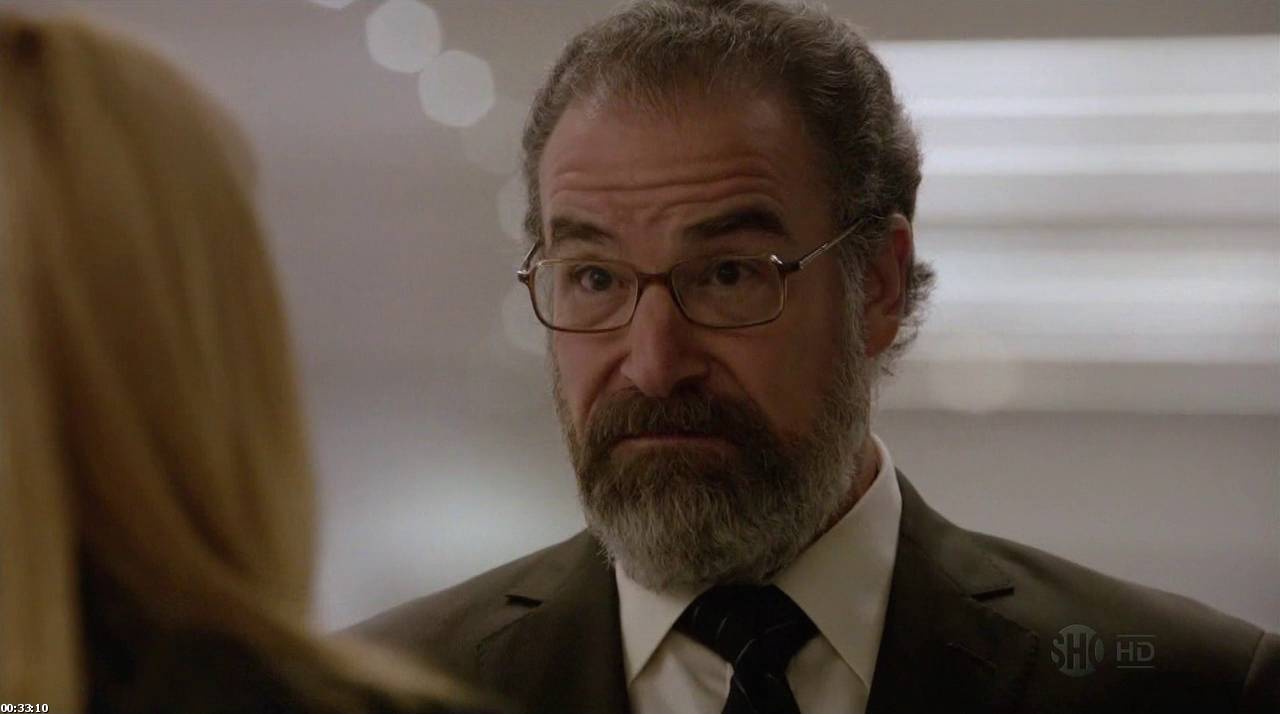

For the past month, Alex Gansa — the showrunner of Showtime’s Homeland — has been making this argument about his own series. The first four episodes of the third season of Homeland — which premiered at the end of September — were monstrously frustrating. Last year’s second season saw the show focusing attention on bizarre subplots and gobbledygook incidents — Dana Brody’s brush with vehicular homicide, Brody’s stealth Skyping with Abu Nazir, Brody’s slapstick murder of a Gettysburg tailor — rather than playing to the strengths that had made it beloved appointment television. But with the promise of Brody’s departure at the end and a return to the business of the CIA, viewers like me came to season three imagining the new possibilities of a clean slate.

What we got instead was four episodes worth of laser-like focus on Carrie’s mental illness and Dana Brody’s infatuation with another reedy, murderous teen psychopath. (Does Dana not have any girlfriends to warn her about these skeevy dudes?) It was hard to bear, and, by the time that the third episode revealed Brody holed up in a Caracas slum being seduced into heroin addiction by a Disney villain, I was ready to turn in my gun and badge. How was it possible that this show could have so little sense of what it was good at? How could it have so little understanding of what made audiences watch it in the first place? Where were the tense interrogations of “Q & A,” the emotional manipulations of “The Weekend,” the fleet-footed fieldwork and high stakes of “The Smile” or “The Vest,” the shocking violence of “A Gettysburg Address”? What the hell is this?

At the end of the fourth episode, we got our answer. Carrie, in collusion with Saul, apparently, had been working deep cover in order to get close to the heavy who ordered the bombing that ended the previous season. All of it, the first four episodes, the breakdowns, the hospitalizations, all that horrible annoying detritus — it was all an act. We had to sit through it because Carrie had to sit through it. We had to endure it because it needed to be endured for a greater purpose. We had to grow to hate Homeland so that Homeland could earn our love.

Needless to say, I loved it. Like M. Night Shyamalan, Alex Gansa had put me, as a viewer, through an intolerably long stretch of stupid television in order to smack me over the head four episodes in. The willingness to intentionally tank four episodes doubled as an acknowledgment that somebody up there knows what really works on Homeland. And Gansa, bless his heart, minutes after the big twist, called out to anyone who would listen that yes this was all on purpose. He told Entertainment Weekly, for example,

I was an amateur magician when I was in my early teens and my favorite magic tricks were always the ones where the magician makes the audience think he’s made a mistake. Then at the end of the trick you realize the magician has been ahead of you all the time. I hope we came close to that.

Gansa repeated this rationale multiple times in reference to the episode — “Game On” — but not everybody was ready to celebrate with me. A lot of critics felt, rightly, bamboozled, or that the pieces just didn’t add up to the intentional prestidigitation Gansa was claiming. What might have played out as a paradigm shift reminiscent of Lost’s famous flash-forwards ended up landing as smug betrayal — the key difference being that Lost tricked its viewers but never stopped entertaining them. A lot of viewers, however, were just relieved. Totally aside from my cinematic masochism, my feelings about the turn of events were aptly summarized by the subtitle of Willa Paskin’s Slate recap: “I’m so happy, I don’t even care that it’s ludicrous.”

But this is what we do when we love a show: we trust it, even when it doesn’t deserve our trust. Oftentimes this trust is anthropomorphized as The Showrunner. This is, to some extent, I think, at the root of this contemporary mythos. We trust the shows we love because that’s what it takes to tune in week-to-week, and, especially with the visibility of auteurs like David Chase and active social media presences like Carlton Cuse and Damon Lindelof, it’s become easy to attribute that trust to a person. We don’t trust that The Sopranos will end well; we trust that David Chase will end it well, and we hold him personally responsible if it doesn’t. And we do this because to commit to a serial drama like this is to forge a real, if marginal, emotional connection to something. On vastly different scales, we trust our mail to be delivered, we trust our friends to come over and snark at Homeland with us, and, after investing hours of time and — for a premium cable show — a significant amount of money, we trust our television shows to know themselves.

From the original sin of letting Brody live past the first season, however, Homeland has been running on trust fumes. After its tremendous first season, the show has been occasionally brilliant — see, for example, the list of episodes above from the first and second seasons — but it has shown itself to be ruinously susceptible to bad ideas or, more accurately, outlandish maneuvers in service of ordinary goals. The Dana/Finn murder plot, for instance, ended up being an elaborate set-up to, um, humanize Finn, or show Dana the meaning of death and responsibility or something? Homeland loves making grand gestures — the car wreck, the VP’s heart attack — that seem, in the moment, to be major events. The show then revels in revealing that those events were only preludes or previews of coming atrocities. Homeland, in other words, loves running the long con, but they’re not always very good at it. And this insistence on setting-the-table with such bridge-burning flourish often comes at the expense of week-to-week interest or even coherence. And, more disappointingly, it forces us to try to care about characters, events, and situations that are ultimately insignificant or tertiary points en route to something else.

And poor Dana Brody is often the prime mover in these distractions. This wayward teen has long been a poster-child for everything that’s wrong with the series. I, however, have always held out hope for her storylines. This isn’t to say I’ve really enjoyed any of them so much as I’ve believed in the possibility of Dana as a character and thus understood why Gansa and company have been so fixated on making her a feature of the series. A credible version of this show might have dispatched Nicholas Brody at the end of season one or midway through season two in order to re-situate focus on Dana and Carrie as twin protagonists. The show might then seamlessly transform from a taut thriller into the emotionally resonant study of trauma, of inheritance, of longing that was always at its heart anyway. Making Homeland about the ordinary lives of Dana and Carrie in Brody’s wake — going to school, going to work — could have made for a great, humane narrative trick and could have made good on the promise of the show’s title. What’s been so disappointing about this season so far is that, to some extent, this is exactly what it’s doing and it sucks. Pairing Dana with yet another loose cannon boyfriend and sending her on a Bonnie and Clyde ’13 road trip made every note ring false, and sending Carrie down a fake rabbit hole didn’t do any better. Homeland can set the table, but it’s been about a season and a half since they served anything even remotely appetizing.

And this problem is extraordinarily clear when it comes to Carrie this season. “Game On” was an exciting turnaround only if it set us up to get back to business. We should want to see Dana fall in love and deal with her terroristic inheritance; we don’t want to see Dana fall in love with a Law and Order case-of-the-week defendant. Likewise we just want to see Carrie do her job. And the hard-earned reward of that magic trick at the beginning of the season was the suggestion that that’s what we’ve been watching all along. Over the past few weeks, a lot of critics have ventured suggestions as to how to “fix” Homeland, and, invariably, all of these suggestions circle around the desire to put Carrie and Saul and Quinn back in the field, doing what they do. As a viewer, I so want to see these characters pulling off clandestine operations that I’ll accept any trick so long as Carrie-Gets-to-Do-Her-Job is the rabbit Gansa pulls out of his hat.

So, to reiterate, in theory, I am pleased as punch that this show decided to snooker us. Being fooled by a series is not the same as being let down by it. And, in the days after it happened, I was filled with the hope that one day, at the end of a riveting season, we might look back and think, “Remember how much we hated the beginning of Homeland season three? Boy was that worth it!” But, alas, it seems like it was not to be. The episodes since “Game On,” have been, to my mind, fairly gripping, admirably old-school jaunts. Javadi’s murder of his wife and daughter-in-law had some of that bracing violence we remember from early season two, Carrie and Saul’s consecutive interrogations had a little bit of that old two-people-in-a-room tradecraft magic, and, despite still dealing with some rather clunky guilt after accidentally killing a kid in the first episode, the show let Quinn have at least one bad-ass move this week when he precision-capped Carrie to save a mission.

But then there’s the pregnancy. In the episode following “Game On,” it’s revealed that Carrie is not only pregnant, but apparently unhappily so — based on the entire drawer in her bathroom vanity filled with urine-soaked, presumably stinky, used pregnancy tests. Too much, too soon, Gansa. I’m all in favor of tricks, but they’re still a tricky business. Coming off of a fake-out like that, a show needs to either drop the mic or hit the ground running. Liberating that character from the confines of the mental institution only to stick her with this seems like, at best, overkill, and at worst, a misapprehension of what’s compelling about this show. Deepening Carrie by giving her this baby underestimates how much we can and have learned about her by watching her work, and creating this manifestation of her relationship with Brody ties him like a millstone around her neck at exactly the moment we should be letting him go. None of the questions it introduces are compelling, and all of the things it resurrects should stay dead.

Some critics have suggested this pregnancy plot is a symptom of aimless writing. Gansa again defends the show against this charge:

To hear that we’re wandering in the woods is just hysterical to us. This is the season we’ve been really conscious and diligent about plotting every little piece carefully. One of those pieces is Carrie’s pregnancy and it becomes very important in this last sweep of episodes.

I don’t doubt that this was planned. Gansa and his team have not lost my confidence that they’re telling the story they want to tell. And I’m sure Carrie’s pregnancy does have a role to play in the last movement of this series. But the same could have been — and was — said about Dana’s car crash, about any number of other silly diversions. With Lost, the question was always, “Will it add up?” When the answer turned out to be no, it felt like a betrayal. I’ve never doubted that Homeland will add up — I do love watching it try — but, at this point, I just don’t know if I’ll care.

Cryface,

Phil.

¤