Dear Television,

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, my favorite show was Star Trek: The Next Generation. There are many reasons for this love, but chief among them was the uniforms. I loved how legible they were: how you saw a color, and a number of pips on the collar, and you immediately knew what that person did and how well they did it. How much, in other words, you could trust them. But it wasn’t a simple calculus: Admirals had six pips, but that actually meant that they were so powerful that they spent most of their time admonishing your favorite character, Captain Picard. Data had two pips and a third that was hollowed out — a symbol of his striving and liminality as, well, a robot, as well as his actual rank of Lieutenant Commander.

Sometimes the uniforms got switched up — I love the casual look from late-stage TNG, when suddenly everyone was chillin’ in mock turtlenecks and comfy zip-up cardigans from L.L. Bean.

When everyone’s in uniform, the smallest variation sticks out. Worf’s baldric (warrior sash, duh) Geordi’s visor, Crusher’s doctor’s coat, Troi’s jumpsuits. But those variations speak: they tell you more about the character, and the character’s purpose in that scene, than even hackneyed expository dialogue could. This is classic melodramatic costuming, in which outfits absorb excess of emotion — things that cannot or should not be said — and communicate them through wardrobe.

In the age of Tom and Lorenzo and detailed, episodic criticism, we’ve grown accustomed to analyzing costume choice. Joan’s roses on Mad Men, Olivia Pope’s literal employment of black and white on Scandal, even a complex color theory of How I Met Your Mother. Unpacking clothes is fun. Clothes porn is fun — I watched Sex and the City, Gossip Girl, Pretty Little Liars as much for the clothes as I did for the characters. But therein lies the problem: the clothes bear more narrative weight than the actors themselves. I wasn’t watching the character, or the action, or the plot — I was watching the clothes; the body wearing them, and his/her acting, choices, and dialogue all seemed to drift away.

But Crusher’s lab jacket never distracted me. It told me something, and then it told me to pay attention because there was going to be some big disease that would spread throughout the ship and take away everyone’s ability to say vowels. Instead of breaking down specific outfits, then, I’d like to work towards a theory of the uniform — and its specific purpose on a show like The Good Wife.

The Good Wife doesn’t have Star Trek uniforms, although it would be awesome if it did, if only because Will Gardner would look GREAT in Riker’s jumpsuit. But the characters’ sartorial choices are circumscribed by their profession: high-end lawyers are some of the last remaining American workers required to wear suits on a daily basis. Professors don’t wear suits, doctor’s rarely wear more than a dress shirt and tie, those in tech apparently just wear hoodies. If you’re in local government, you only wear a suit if you’re Leslie Knope or Chris Traeger. If you’re on the police force, you only wear a suit if you’re a detective. So what do we have? Bankers, politicians, lawyers. Bankers are boring and corrupt, at least in the current public imagination, but it’s no coincidence that two of the best shows on broadcast deal with people from the last two groups: Scandal and The Good Wife.

In landscapes of power and prestige, everyone has to look just-so. You need to look respectable and put-together; you don’t want to blend into the background entirely, but your wardrobe should never become more important than your argument or your ideas. Even a bow-tie can speak louder than it should.

In these workplaces, gender display shouldn’t trump your message, but you also don’t want to distract with any sort of gender confusion. Hence: the woman’s power suit, which apes the standard male suit, with its boxy, square shoulders and well-tailored lines while subtly emphasizing the waist and breasts. The woman’s suit says I’m powerful but I’m a woman: be impressed, but don’t be scared.

The Good Wife may have a modicum of what Phil calls “blazer porn,” but it’s all about uniforms. Ninety percent of our time with these characters is spent at the law firm or on case business — even when they’re drinking whiskey, they’re wearing their uniforms.

Let’s start at the center. According to The Good Wife’s costume designer Daniel Lawson, Alicia Florrick (Juliana Margulies) has around 350 suits in her closet. These suits have a very specific color range: grey, darker grey, lighter grey, red, brighter red, navy, and darker navy. Sometimes there’s a bit of emerald green or even a bit of white tossed in, but that happens once a season, if that. When Florrick was shamed by her husband’s very public prostitution scandal and attempting to reintegrate into a workplace, her clothes were simple, with lots of grey pantsuits. As Lawson explains, she probably didn’t have a ton of actual suits, so her first season was mostly throwing shit together and trying to be as unassuming as possible. Still, the suit reigned.

Yet as Alicia rose through the ranks in the firm, had a steamy affair with her boss/old flame, and laid down the law with her husband, her suits got wild, and by wild, I mean they got peplumed.

More tailored — more willing to highlight her body — and more bold. A bow here, some colorblocking there. It’s still the uniform, but it’s a uniform she’s making her own, just as she reforges her identity from politician’s wife to that of a working, single, even sexual mother. It’s a subtle transformation, but I think it reflects the subtle work the writers are doing. You don’t need to thump the audience over the head by suddenly forcing Alicia into Samantha’s leftovers from Sex and the City to communicate a sexual and professional rebirth. All you need is some peplum and a pop of color.

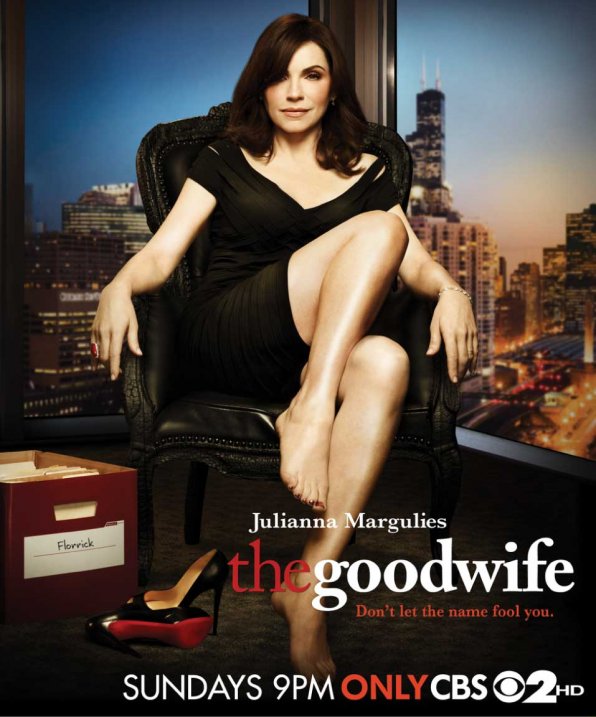

When you look at promos for the show, however, Alicia’s rarely in uniform.

Promos, especially promos for a show with a title as horrible as The Good Wife, employ visual rhetoric that isn’t as subtle as the show’s. In a one-sheet, peplum can’t quite convey the same message as the hyper-sexual pose above — a pose, and a willing objectification, to which the “real,” non-ad Alicia would never submit. The clothing is off because the entire message is off: this isn’t a show about sexy lawyers banging each other all day; it’s a show about the intersections of sex and professionalism, about duty and desire — the sort of subtlety that a uniform can reflect so skillfully.

Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski) gets more to play with, in part because she’s just so much more powerful. I was telling Phil that while I like Alicia, I love Diane, mostly because she’s an icy, ball-busting second-wave feminist, a description I intend as the highest of high compliments. Many of my female mentors fit this description — women who had to fight for their place in their field, who sacrificed tremendously, who didn’t worry about “having it all” because what they really wanted was a place at the table. These ladies take zero shit, but they’re also extremely mindful of the type of behavior and presentation necessarily to earn and sustain their places of power. Diane’s uniform — and the perfect way she arches her eyebrow — convey as much.

Diane isn’t middle-aged. She is, as the French would say, “d’une certaine age” — an age that affords a certain knowledge and luxury. She knows what looks good on her, and she has the capital to spend on it. Tailoring, jewelry, brooches, amazing, precise haircuts — she’s got it. Sometimes her uniform tends towards the Alicia-esque suit, but she also rocks the sheath dress like a perfectly-fit glove, usually with some statement jewelry. These aren’t chunky faux-jewels strung on twine and purchased from Etsy — we’re talking straight up pearls and gold, a way of underlining I fucking made it. We don’t need clunky flashbacks or cheesy speeches about Diane’s past — that jewelry, paired with those elegantly tailored, square-shouldered dresses and that exquisite $200 haircut, which she may or may not pay someone to blow out every morning, says everything.

Costuming can provide instant character development, but it can also provide instant contrast. Mamie Gummer’s sorority girl take on the lawyer uniform not only communicates what tactics she’ll adopt in the courtroom, but the intensity with which Alicia despises her. And as for Kalinda (Archie Panjabi), she still wears the high-powered uniform, it’s just a leather version of it.

There’s the blouse, the vest, the tailored skirt, the nylons, the expensive footwear — it’s a power suit for the street, and I don’t mean “street” as in “I grew up on the streets,” I mean the ACTUAL STREET, like walking around, performing surveillance, getting people to talk to you. Alicia and Christine’s clothes individualize them while still allowing them to hew to the expectations of gender and power performance, and Kalinda’s do the same. With her rotating wheel of knee-high boots, black skirts, and leather jackets, she looks like a powerful person, but instead of using that power to persuade a jury, she’s using it to persuade anyone to do anything she wants.

A lawyer needs a certain kind of authority and the uniform to convey it, and a street investigator needs quite another. One is rooted in class and intelligence. . . . .and the other is predicated on sex. As an Indian woman in an enduringly (if quietly) racist society, a woman like Kalinda knew that she’d never be an Alicia or a Diane, so she uses a uniform that will deflect attention from her race and make her the best at her job. Everyone’s too busy looking at her skirt to realize that she’s swindling them — and making a lot of money doing it.

And when The Good Wife characters take off their uniforms, it’s like Carnival: a time for true hungers and desires to run wild. Think of Alicia’s red dress at the gala, or Diane’s target shooting outfits. They’re not revisions of their uniforms so much as extensions, an opportunity to further underline character and whimsy and sex, much as the ventures into the Holodeck, and the creative costuming it afforded, did in Star Trek.

When she was cast as Diane Lockhart, Baranski told the costume designer that she didn’t want to be a “walking fashion Barbie.” Name partners in a Chicago law firm may spend a lot of money on high-end clothes, but they weren’t changing clothes twice a day or wearing hot pink pumps.

But her concern wasn’t just realism — turn Lockhart into a fashion Barbie, and suddenly the conversations about Diane are all rooted in clothing and consumption. Put her in the lawyer uniform, and she can still be fashionable, but conversations about her character become ones of action and speech: what does she do and say, and how does she do and say it?

In academia, female scholars, myself included, often fixate on what they wear, whether in the classroom at a conference. I’ve spent as much time figuring out what to wear as I present my paper as I’ve spent on the paper itself, and I’m by no means alone. Your clothes have to send all sorts of messages, layered with the same density as an academic argument. Footwear, tights, skirt length and style, jacket, satchel, earrings, make-up, hair — people say that academics have it lucky in the wardrobe department, because you can be as informal or formal as you’d like, but that sort of freedom actually makes things harder, not easier. Men have to deal with some of these overdetermined fashion choices, but it’s nothing compared to what women negotiate. Wardrobe matters because wardrobe communicates — which is precisely why so many schools demand uniforms.

If melodramatic costuming, particularly female costuming, was employed to express the inexpressible, then the contemporary uniform underlines these female characters’ ability to speak for themselves. Olivia Pope, Alicia Florrick, and Carrie Mattheson all wear uniforms. It’s no mistake that they’re the most self-actualized, complex, and compelling characters on television.

Don’t Underestimate the Peplum,

AHP

¤