MASTERS OF SEX, “PILOT”

Dear Television,

Let’s talk genre.

WHEN I WATCH Masters of Sex, here’s what I see: 1) a hospital, an operating bay, white lab coats, doctor politicking, neurotic middle-aged male with horrible home life (medical drama); 2) ‘50s hairstyles, outdated politics played as plot points, beautiful mid-century modern homes, big band jazz (period piece); 3) women of various social classes suffering under patriarchy, women connecting with other women, women triumphing over societal expectations (social melodrama).

I realize that genre-hybridity is nothing new, especially given the trajectory of the last decade, when the narrative complexity of “quality television” has filtered down to everything from ABC Family teen dramas to CBS procedurals. Indeed, genre hybridity is one of several characteristics that have been used to distinguish the quality (I don’t even own a TV) from the dreck (the medium of the masses). If normal television was aesthetically uninteresting, quality television was filmic, even beautiful. If normal TV was the product of collaboration, quality television was the brainchild of a single showrunning genius.

And if normal television was dependent on genre, then quality television would mash the hell out of those genres. The Sopranos was a gangster melodrama; Carnivale was a paranormal period piece; Deadwood was a Shakespearian Western. Take audience’s well-trained genre expectations to lure them in and then, with various degrees of grace, showily flip those expectations. The mob boss who goes to therapy, the old West kingpin with various Freudian affiliations and a natural talent for soliloquies. It was different and surprising and psychologically complex, which, in today’s critical climate, are codes for “good.”

But in case you haven’t heard, we’re at the end of this latest “golden age” in television. The innovations of the early 2000s seem tired — the sort of thing that also-ran quality networks, like FX, employ. (The Americans, after all, is a family melodrama dressed in spy thriller ‘80s wardrobe). To get noticed in the vastly overpopulated quality landscape, you can’t just mix two genres. As Masters of Sex proves, you need at least four.

But Masters is trying to be all the quality things to all the quality-television-watching people, and the multiplicity of purpose is, at least at this point, diluting the show’s potential power. It’s combining the addictive energy of a procedural, the charismatic anti-hero of an HBO drama, the sexy allure of a period piece, and the weepy triumph of a soap. It’s the jack of all trades, ER + Breaking Sexy Bad + Mad Men + Nashville.

Granted, that kind of sounds like a perfect show, but the more I think about it, the more it seems like the televisual version of the soda fountain “graveyard” — you think that Coke and Mountain Dew and Root Beer and Grape Soda will taste bomb together, but you just end up drinking four sips and apologizing to your mom for wasting her 99 cents. Jack of all trades, as your Granddad would say, and the master of none.

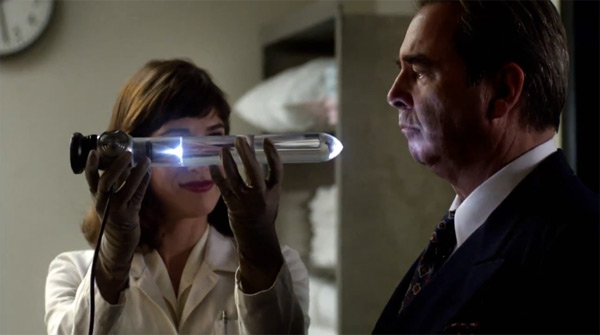

The point, then, is that Masters of Sex can’t decide if this is the role it will take. The sex research is played as a mix of sight gags (an enormous glass dildo named ‘Ulysses’; a keyhole shot of Beau Bridges peering through the end of said dildo while it’s implanted in a subject, which gives the curious feeling of a vagina filming a man’s eye) and very serious, very impassioned speeches from Dr. Masters (Michael Sheen) concerning the importance of sexual knowledge. We have a classic quirky Man of Science, but his sidekick and quasi-protege, Dr. Ethan Hass (Nicolas D’Agnosto), seems to have hopped over from a teenaged version of Grey’s Anatomy, with the accordant levels of strife, sexual yearning, and paralyzing jealousy, plus a little red-faced drunken woman-battering. Granted, Hass’s angry slap is a chance to demonstrate that our female protagonist, Virginia Johnson (Lizzy Caplan) is the type of woman to hit back. But didn’t I know 30 minutes before, when she introduced Hass to the concepts of cunnilingus and fellatio?

As Johnson, Caplan is winningly charismatic and lacks the meekness that typify female portrayals of this time. Johnson is a trailblazer, which is part of the reason she gets a show about her. I like that she’s kind of a bad mother and only kind of feels bad about it. But the female characters that surround her are storybook foils: the hard-boiled strong-accented prostitute and the neglected delicate flower of Mrs. Masters, whose self-loathing “I can’t get pregnant” narrative seems torn from a Lifetime movie of the week. I get that Masters is using private spaces to refract and reframe the public ones, but right now it feels a bit like a thoroughly discombobulating narrative funhouse.

Phil might have inadvertently figured out part of the problem in his piece on Monday, suggesting that unlike Mad Men, with its immaculately paced commitment to showing the politics of both the era and its characters, Masters of Sex is just fine with telling. Exposition abounds: here’s what we’re doing, here’s who I am, here’s every central conflict that will define the season — all in Episode One!

It’s the sort of narrative economy we’ve come to expect from feature films, which need to finish setting the table before the end of the first act. While quality TV has embraced the aesthetics and style of feature film, it’s rejected its narrative tropes. Television, at least this type of television, shouldn’t be that efficient. It should take weeks, if not seasons, to figure out who our characters are. And Masters has made concessions to that understanding: we have a vague sense that Masters contains multitudes. But the few promising character arcs of Episode One have already been solved by Episode Three, and it almost feels like the writers fear that every episode might be the last, inserting a loose end (a brazen prostitute; a gay male prostitute) and tying it up as quickly as possible.

Is Masters of Sex a simple show or a complex one? I honestly can’t decide. I think it, like most of us, sees value in both. Not every show has to have the seven-season pre-planned arc of Mad Men, but there’s something to be said for subtlety and allowing your viewers to reach their own conclusions about, say, a character’s place in the world without explicitly ventriloquizing it through a job interview. It oscillates between trying to be all genres at once and playing up a single one; its main commentary is on sexual politics, but it doesn’t want to be accused of ignoring race or class, so it inserts those as well — a sideplot involving an African-American patient, for example, is so thin, and so transparently instrumental to establishing the character of the white protagonist, that it’s embarrassing to watch. Masters committed to historical realism (just look at Masters’s dining room) but wants to play with anachronistic music (an unaccountable James Blake song plays over a montage at the end of Episode Two). Its project, like that of its protagonist, is undercutting the myths of human sexuality, yet it depicts a female in the throes of orgasm within ten seconds of stimulation.

I think we can trace this super-genre mishmash, and its unsettling shifts in tone, to a finicky embrace and flight from melodrama. We often employ the term “melodrama” interchangeably with other genre terms — Western, Sci-Fi, Thriller, Rom-Com — but as film scholar Linda Williams has very convincingly argued, melodrama isn’t a genre so much as a mode: “a peculiarly democratic and American form that seeks dramatic revelation of moral and emotional truths through a dialectic of pathos and action.”

In other words, melodrama is more than the sum of generic structures and set pieces; it’s an entire approach to narrative. Under this definition, melodrama includes everything from Pretty Little Liars to The Bourne Identity. In the 19th century, melodrama’s function was to make the world morally legible — a sense of existential comfort as the church ceased to be the measure of all things. In the late 20th and 21st, melodrama seems to highlight the moral illegibility of the world — which, one might argue, provides a very different sort of comfort.

The melodramatic mode has always been characterized by excess — excess of emotion, specifically, which not only shows up in the form of tears and stoic glances into the horizon, but that which cannot be said overflows into the mise-en-scene and costume. Tom & Lorenzo’s epic fashion breakdowns enjoy crazy popularity because Mad Men employs wardrobe and setting to tell the story as much as dialogue — the ultimate showing over telling. But Masters is an unrepressed show about a historically repressed subject: it depicts sex when most people wouldn’t even speak it; it shows and tells.

That should be the formula for a fascinating show. That’s the high concept; the way the show was most likely sold: like Mad Men, but turned inside out. Instead of endlessly meditating on the stultifying ennui and lack of identity of the ‘50s and ‘60s, let’s use science to actually figure that shit out. I realize it’s too early to criticize the show for what it hasn’t yet become. But as we track the progress of the series, its ability to sort through its self-generated generic haze may be the barometer of its success. Otherwise, it’ll just be a Graveyard, filled with so many flavors as to taste like nothing at all.

Grape Soda 4 Life,

AHP

¤