By Amy Hawkins

With an eye toward providing readers interested in both China and James Joyce with a fitting reading for the week in which Bloomsday falls, we are happy to have a chance to run an interview with Xue Yiwei, provided to by Amy Hawkins, a Beijing-based writer who happens to be that author’s niece. The interview’s relevance to Bloomsday will quickly become clear below —Jeff Wasserstrom

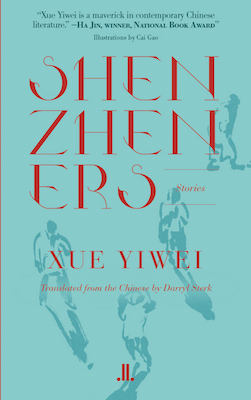

For a writer who focuses exclusively on China, Xue Yiwei has become something of an alien in his home country. For the past decade, he has lived in Montreal, penning over 20 of novels set in China, which have only recently started to be translated into English. He has been described as a “maverick in contemporary Chinese literature” by fellow novelist Ha Jin, and as “Montreal’s Chinese literary secret” in the Canadian press. Earlier this year he was awarded the Diversity Prize at the Blue Metropolis Montreal International Literary Festival. His first work to be fully translated and distributed in English is Shenzheners, a collection of short stories set in Shenzhen, exploring the loneliness and “inner life” of different people lost in the urban environs. Inspired by James Joyce’s Dubliners, the book, fluidly rendered into English by translator Darryl Sterk, follows a recent spate of Joycean popularity in China. I spoke to Xue, who is also my uncle, about the influence of Joyce on Chinese literature and what the similarities are between the Shenzhen of today and the Dublin of a century ago.

AMY HAWKINS: You dedicate Shenzheners, a collection of short stories and your first book translated into English, to “the Irishman who inspires” you. Why James Joyce?

XUE YIWEI: I read Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man from Chinese translation in early 1980s when I studied in Beijing and at the University of Aeronautics and Astronautics as a Computer Science student. I was amazed by Joyce’s poetic exploration of the human inner world and his examination of individualism. I was also struck by his politics based on individualism. All this has left string marks in my own writing. “I fear those big words,” Stephen says in Ulysses. For those of us who went through “big words” of the Cultural Revolution, this has a special attraction. I feel grateful to Joyce. I am his life-long student.

In Joyce’s eyes, Dublin is a decadent city, paralyzed and paralyzing, a symbol of the old, while Shenzhen is “the youngest city” in China. What is the connection between these two extremes?

Yes, in some sense, Joyce’s Dublin is a dying if not dead city that fears change, while my Shenzhen is a new-born city thirsty for growing, for change. They are two extremes on the surface. What connects them is the inner world, which is universal, which is delicate, which is always emotional, fragile and full of anxiety. The inner world is where epiphany sprouts. In Shenzheners, there are a few teenage narrators, such as the one in “The Peddler” and the one in “The Prodigy.” “Driven and derided by vanity,” they bear some features of the narrator of “Araby” from Dubliners, and their eyes burn “with anguish and anger.” The relationship between man and woman is another major theme in both Shenzheners and Dubliners, which is in part my response to Joyce’s “The Dead”. Through the inner world, the youngest city in China has a dialogue with the solitude of Dubliners that has existed for 100 years.

Of all the western literary works that have been translated into Chinese and published in China since the end of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s, Joyce is particularly popular. Finnegans Wake, for example, sold more than 8,000 copies in its first month when it was translated into Chinese in 2013 — 3,000 more than the mainstream popular novel Atonement by Ian McEwan. Why do you think Joyce is so popular? And what is his influence over Chinese writers as well as readers?

To be honest, compared to Kafka, Camus, Falkner, Hemingway, Garcia Marquez…Joyce’s influence over Chinese literature is very limited and short-lived. The decade between the late 1970s to the late 1980s might be considered the period of this ‘influence.’ At the time, quite a few young writers were fascinated with the concept of stream of subconscious as well as Joyce’s stylistic novelty, like not using quotation marks or a long paragraph without punctuation. Among all his works the most influential one in my opinion is A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man whose protagonist’s conflict with the country, the church and the family echoes the suffering of the Chinese generation growing up in the turmoil of 1960s and 1970s.

We should be very cautious about so-called Joycean fever in China. An item of commodity that we could display on the shelf is different from a literary work that we could learn from. The mainstream of contemporary Chinese literature is realist rural literature that based on the agricultural tradition. And the dominant ideology is collectivism. The so-called urban literature, of which Shenzheners is considered as a symbol, didn’t draw much attention until the beginning of the 21st century. Joyce is too urban and too individualistic to be an icon of the Chinese writers. Most Chinese writers are more concerned with stories, not the way of telling the story or the nuances of language. The Joycean passion for language seems too excessive and too pertinacious to follow.

But in the 1990s, two Chinese translations of Ulysses came out, and it was widely reported in the West that Joyce was a surprise hit in China.

I don’t think the noise about Ulysses in the 1990s had much to do with literature. The media made them dramatic to draw attention, but the novel’s influence over Chinese literature was indeed very limited. No doubt the language itself has lost some of its allure after translation, and the themes of father-son relationships or man-woman relationships never really resonated with the psyche of the Chinese writer. In fact, in more than two decades, I have only known one colleague who claimed that he had “finished” reading Ulysses.

And what about the popularity of Finnegans Wake?

I am not so familiar with the Finnegans Wake fever because I had left China by then, to live in Canada. Still, it is a respected academic adventure to translate such a book that is fundamentally hostile to translators and readers alike. As far as I know, its completion is a great achievement. But the alleged Chinese commercial success of Finnegans Wake should not be taken seriously and once again, I must stress that its influence over Chinese literature is insignificant. Yes, many writers as well as ordinary readers talk about it the publication has drawn considerable attention. But I have never have met a reader that has really read it, not to mention finished reading it. I don’t think there are many English-speakers who have finished reading it, either. Commenting his colleagues’ reading of Ulysses, Martin Amis once said, “They read it – but have they read it, in the readerly fashion, from beginning to end?” For Finnegans Wake, I think he might change the last word into page 10 or even the second page. Don’t forget that China is a huge market craving Western culture. Any “big titles” from the West could get a hot response from Chinese readers. Along with Finnegans Wake, there has been excitement surrounding One Hundred Years of Solitude in recent years, and even Less than One, Joseph Brodsky’s collection of essays. It’s not an accessible book but still a lot of ordinary readers rushed to buy it.

You’ve written about Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book, a history of Joyce’s battle to publish Ulysses. What made you want to draw Chinese readers’ attention to this book?

The Most Dangerous Book is the most interesting book I have read for the recent years about Ulysses. It is profound and inspiring as well as beautifully written. And it is about free expression and censorship. These are two key themes concerning the Chinese literary reality. I am glad its Chinese version will come out soon. I hope people will learn a lesson from the experience of the most dangerous book. Stephen Dedalus [Joyce’s literary alter-ego] said history is “a nightmare” from which he is trying to awake. But after awaking, we should see the beam of hope. The Most Dangerous Book is about triumph of literature. It brings hope to those who are struggling. It is a book timely suitable for the current cultural situation in China.

Similarly to Joyce, you write about your home country from abroad. Do you see yourself as living in a self-imposed exile? What do you think the effect of this detachment is on your writing? Considering reality of censorship in China, do you think that writers are better placed to write about China from a place of distance?

Globalization has made the classical situation called “exile” complicated if not surreal, no matter if it is forced or self-imposed. I see myself as a writer living in a strange land. This detachment enables me not only to concentrate on writing but also protect my memories about the 1970s and 1980s, which are the foundation of my writing, from the pollution of the instantaneous reality. Yes, I think writing about China from a place of distance is a valuable position for a fiction writer. In the early 1990s after the publication of my novella Decembre 31st, 1989, which deals with that eventful year, I had to stop writing for almost six years. I know what forced silence means for a writer.