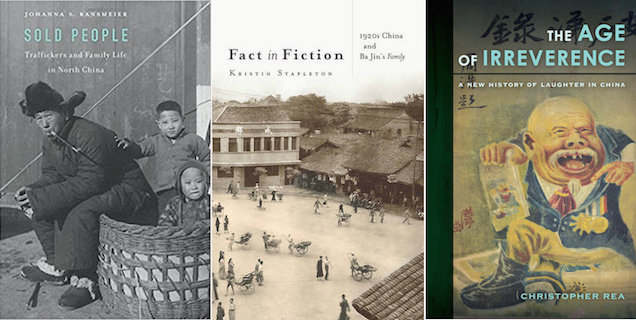

It’s easy to imagine a book on the trafficking of people in China around a hundred years ago that begins with a chapter that cites various anthropologists and scholars in other disciplines, while placing the Chinese historical phenomenon into comparative and theoretical perspective. It’s also easy to imagine a different book on the same subject opening in a totally different, more literary manner. This other book might begin with the author stitching together material from archival sources, such as confessions, to create a tale about real people that reads like a short story. What I could not have imagined a week ago was a book that did both of these things, but I can now. What made the difference was picking up University of Chicago historian Johanna Ransmeier’s Sold People: Traffickers and Family Life in North China, which was recently published by Harvard University Press.

The book’s first two paragraphs introduce us to feisty Widow Chen and her fraught working relationship to a man known as Old Liao. Then comes a brief section that explores the value and limits of using English language terms such as “slavery” and “bondage,” which have various kind of baggage associated with the pasts of other countries, to describe specific Chinese historical practices. This alternation between storytelling and analysis continues for another twenty pages. And, against all odds, it works. After finishing the book’s “Introduction,” over the course of which Widow Chen’s character in particular becomes increasingly well rounded and interesting, it was easy for me to imagine recommending Sold People to two very different sorts of friends. I could tell a friend whose favorite history books are story-driven ones like Natalie Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre that, if in the mood to pick up a book on China, this might be the one. I could also, though, bring it to the attention of a colleague curious to know if anything in my field could be of value to an advisee doing dissertation work on the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Having realized that, even with its two-books-in-one feel, a mini-review of Sold People wasn’t quite enough for a China Blog post, I have decided to slip in mentions of two other worthy books. They, too, are quite recent publications, though neither is hot off the presses like Sold People. And they, too, are largely or exclusively about the early 1900s.

One of these books is SUNY Buffalo historian Kristin Stapleton’s Fact in Fiction: 1920s China and Ba Jin’s Family, which Stanford University Press published last year. Its focus is on the social history of the Sichuan metropolis of Chengdu early in the twentieth century. That city is the setting for Ba Jin’s Family, a famous novel from the period that is often used by people like me who teach courses on modern Chinese history. Stapleton sketches out life in Chengdu via a series of chapters, each of which is devoted to one of the social groups to which a significant character in Family belongs. One chapter, circling back to Sold People, is titled “Mingfeng: The Life of a Chinese Slave Girl.”

The final book I want to give a shout out to, which is on a decidedly lighter topic than human trafficking, is The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China. Published by the University of California Press in 2015, its author is Christopher Rea, a versatile specialist in Chinese literature at the University of British Columbia, whose accomplishments include having earned a major book prize from the Association for Asian Studies for this work, and, before that, somehow convincing Eric Idle of Monty Python fame to write a blurb for his volume! As for its contents…rather than try to describe what Rea does, I’ll simply point those intrigued to find out more to the introduction to and excerpts from the book available at the China Heritage site, an excellent new online venture cooked up by Geremie Barmé with which LARB’s China Blog has done some collaborating already and with which we hope to do more in future.