The invaluable China Digital Times website, which has a regular “Drawing the News” feature and publishes related illustrated e-books is releasing a new collection today — Watching Big Brother: Political Cartoons by Badiucao. Along with a rich sampling of works by the artist, who was born in Shanghai and is now based in Australia, the ebook includes an interview with Badiucao (a pen name) conducted by Sophie Beach, executive editor of CDT. The Los Angeles Review of Books has been given exclusive rights to run an excerpt from that interview for “The China Blog.”

SOPHIE BEACH: You have been the subject of Twitter smear campaigns in recent months. Who do you think is behind these attacks, and what was your response? Has it changed your attitude toward your drawing? Has it changed your approach to being active on the Internet?

BADIUCAO: In recent years, I have been subjected to large-scale Internet attacks twice. I believe these attacks are linked to the Chinese government’s control of the Internet, for two reasons: First, both attacks happened after I had drawn cartoons in support of human rights activists who had been imprisoned, and the drawings had been picked up by Amnesty International and the international media. Second, all the slanderous attacks against me use show the political positions of the Chinese government—the language used by the attackers is full of clichés and their user profiles seem to be automated fake accounts. This shows that these attacks are not from individuals, but are organized systematically. The goal of this kind of attack is not just to threaten me, but possibly to pollute search results for “badiucao,” and to block the visibility of my cartoons online.

The first time I faced an online attack, I was terrified. I had previously received sporadic threats, but never this type of coordinated attack. Some “fifty centers” [a nickname for people paid by the authorities to post comments on line] wrote several essays to specifically “expose the ugly soul of hypocrisy under my skin.” From this essay I could see that they had very carefully examined my words and collected specific personal information about me. When it reached this degree, I slowed down my drawing.

But then, I felt I couldn’t control my creative impulse. I also understood that the only way to overcome the fear of such attacks was to make them public and to continue to draw. It is like when facing the threat of terrorists: once you compromise, the other side will only intensify. The second time I was attacked, I could face it calmly. I even saved all the words and articles attacking me, to keep as a witness. In the future I hope to use them as creative materials.

Since we last spoke, fellow cartoonist Rebel Pepper has been living in exile in Japan after being attacked in the official media in China. Do you think there is any space currently for political cartoonists living in China, or is it just too dangerous?

I believe that the Chinese space for political cartoonists in the mainland has already closed.

In the era when Weibo [a Chinese counterpart to Twitter] first launched, online satirical cartoonists were very active. We could see Kuang Biao, Dashixiong, and dozens of other cartoonists commenting on current events. But now, I almost never see domestic cartoonists’ work.

But I don’t think we can be too hard on cartoonists for not fulfilling their full duties because the threats they face are real. Like the incident with Rebel Pepper; if you have no way to get away, you may have no choice but to shut up.

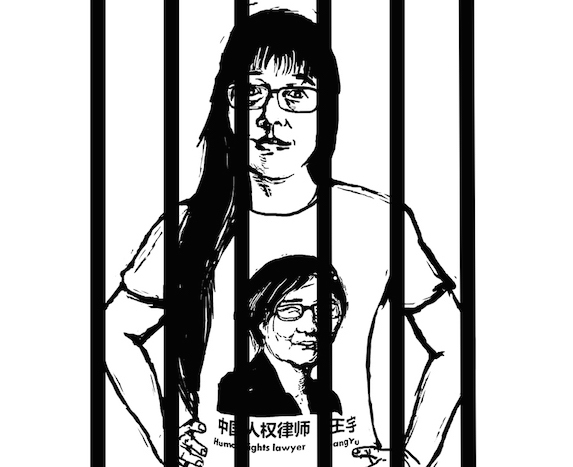

Read more about this image at China Digital Times.

Over the past year or so, you have drawn several portraits of human rights defenders that have been very well-received online. They are a departure from your previous, more narrative drawings. Is this a direction you plan to take your work in the future, away from the political “cartoons” and into more traditional drawing and painting styles?

This year, I drew several portraits of rights activists who had been detained.

I had three reasons for doing this: First, this year, the suppression of human rights activists was more severe than in years past. In the first half of the year the pressure was concentrated on NGOs and journalist groups. The second half of the year saw the crackdown on rights lawyers. It seems that after the authorities cleaned up competition inside the Party, they had a hand free to interfere with social dissent. Moreover, authorities used CCTV confessions as propaganda. Second, for those who have been on Twitter a long time, they understand Chinese rights activists and when these familiar people encounter problems, it can inspire a strong sense of solidarity. Third, from analyzing the two attacks on me, I have learned that authorities are very concerned about international media attention on the suppression of human rights activism. This encouraged me to continue creating portraits of China’s prisoners of conscience. Cartoons and portraits can create a unified visual symbol, which can help spread the message and attract sustained attention, in order to create pressure from public opinion. Maybe this pressure can improve the situation for those who are imprisoned, as well as comfort the family members of the persecuted.

But, this will not cause me to give up paying attention to and finding inspiration from current events. Showing solidarity for human rights activists and commenting on current events are not in conflict with each other; they both offer excellent opportunities to profile China. However, if you only have activists’ portraits without their background stories or a depiction of China’s overall environment, my work will become dull and weak, and even risks becoming a simple and emotional propaganda tool.

As for my own development, I will not stop creating cartoons. Cartoons and the Internet are already a part of my life. Drawing cartoons has helped form me and my identity.

Of course, I am now trying to use more artistic means to express myself: print-making, oil painting, sculptures, installations. Different media signify different forms of expression, and different platforms (for example streets, galleries, museums) mean different audiences. I hope to become as diverse an artist as Banksy or Ai Weiwei.