By Anne Witchard

The title of James H. Bollen’s new book — Wallpaper: The Shanghai Collection — makes an ironic gesture towards the materialism and consumerism that drives the ongoing destruction of Shanghai’s domestic heritage. This collection of wallpapers is available only as torn remnants clinging to half-demolished walls. The conceptual framework of this project could not be more apt. The images are grouped according to quotations from the essays of William Morris, genius both of wallpaper design and of a bygone socialist optimism. The peeling layers of bulldozed homes reveal the declining fortunes of successive generations of Shanghai’s shikumen tenants. Where once papers from Morris & Co. might indeed have graced these walls, the touching reminders of more recent adornment — Western Christmas decorations, movie posters, girlie calendars or children’s scribbles — seen through Bollen’s lens, are an arresting comment on history, architecture, and aesthetics in the context of contemporary Chinese aspiration.

ANNE WITCHARD: Can you tell us how you first made the connection between what you were seeing in Shanghai and what William Morris was thinking about in the 1890s?

JAMES BOLLEN: As I’ve written in the foreword to the book, seeing the V&A’s Aestheticism: The Cult of Beauty 1860-1900 exhibition in 2011 set me off thinking about the connections between the abandoned decorations of derelict Shanghai housing and the subjects William Morris discussed in his lectures published in Hopes and Fears for Art (1882).

You take a total of ten quotations from Morris’s Hopes and Fears for Art — can you tell us how you chose to group the images according to the quotes?

The photographs are like a visual echo of the main subjects Morris talked extensively about in his lectures, namely aesthetics, architecture, history, and art. My book begins with his ideas about aesthetics and one of his most famous sayings: “Have nothing in your houses which you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Following that are Morris’s views on architecture and history. Many of the interiors of the homes I photographed were in Shanghai’s less wealthy areas. Others, particularly the ones with wallpaper, were in the city’s more prosperous ones downtown. I feel that Morris would recognize their destruction in some cases as being the result of what he called “profit mongering.” The final group is tied to the previous subjects and Morris’s ideas about and views on art. In his biography, E.P. Thompson wrote that Morris stated the “death of all art” was preferable to its survival among an elite.

Could you say a few words about these three images that are grouped under “Modern civilisation is on the road to trample out all the beauty of life”?

Xuejia Road, Huangpu District 2011 (p. 42)

Lufeng Road, Zhabei District 2010 (p. 43)

Gongping Road, Hongkou 2010 (p. 45)

The timber of the housing on page 42 would have been stripped away, and so the nude woman on page 43 is a play on that. I found quite a few Christmas decorations, though given that Shanghai is mainland China’s most international city this isn’t really surprising. This one of a pair of Bambi lookalikes pulling Santa on his sleigh is by far the most imaginative.

The book’s central section is of eleven consecutive images under this quotation from “Art Under Plutocracy”: “So long as the system of competition in the production and exchange of the means of life goes on, the degradation of the arts will go on; and if that system is to last forever, then art is doomed, and will surely die; that is to say civilisation will die.” Can you say something about this selection?

In this section the photos sequence the process of demolition in Shanghai. The newspaper (p. 58) is a stand-in for the eviction notices pasted outside people’s homes when they are slated for demolition. The red painted character for “to be demolished” (p. 59) is also painted outside them.

Kunming Road, Yangpu District 2011 (p. 58)

Huimin Road, Yangpu District 2011 (p. 59)

The following photos (pps. 60-63, 65) refer to the various tactics used to drive people from their homes. One is to smash in their roofs and windows (which I discuss in the book’s introduction) resulting in water damage, eventually condemning the buildings as uninhabitable.

Qufu Road, Zhabei District 2014 (p. 60)

Hejian Road, Yangpu District 2011 (p. 61)

Fuxing Middle Road, Huangpu District 2013 (p. 62)

Shunchang Road, Huangpu District 2011 (p.63)

Moganshan Road, Putuo District 2010 (p. 65)

Also mentioned in the introduction is that these homes have everything of any value stripped from them — in the case of page 67, the copper from the electric wiring and plastic from the socket.

Yulin Road, Yangpu District 2011 (p. 67)

The disturbing looking drawings of faces on page 68 to me symbolize those people who resist having their homes demolished.

Miezhu Road, Huangpu District 2011 (p. 68)

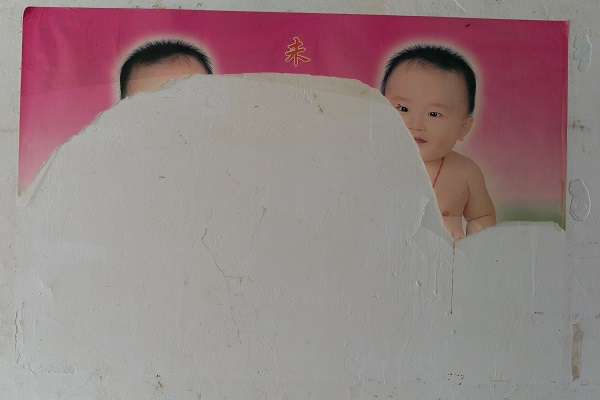

The missing face of the baby twin on page 69 refers to their forced removal.

Ruihong Road, Hongkou District 2010 (p. 69)

The image on page 71 is the final destruction of the housing itself.

Xujiazhai Road, Zhabei District 2010 (p. 71)

It’s now more than 100 years since William Morris argued capitalism will end up destroying civilization, which brings me to the final quotation in the book: “The past is not dead, but is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make” (William Morris’s Preface to Mediaevel Lore (1905) by Robert Steele). We should pay attention to Morris’s assertion that the past, and with it his views and ideas, is not dead. After all so much of what he said and wrote is still relevant and rings true today, and the main reason why I have put his words together with the book’s photographs.

Finally — how might you explain the undoubted aesthetic appeal of urban demolition and decay?

I think it’s a combination of how surreal derelict structures look, particularly when surrounded by new developments, and their history. It’s emotional to think of “all the generations… that have passed through” buildings in a state of demolition and decay. And they are symbols of mortality — we like them will one day disappear. While quite gloomy to contemplate it’s interesting that these buildings share the same cycle of birth, life, and death as the people who lived in them.

James H. Bollen is a British photographer and author based in Shanghai.

Anne Witchard is Senior Lecturer in English, Linguistics and Cultural Studies at the University of Westminster, London