In the wake of Liu Xiaobo’s tragic death, Western news sites have been filled with assessments of many things related to the literary critic turned prisoner of conscience and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Few efforts have been made, though, to gauge reactions to Liu’s treatment and demise on the Chinese mainland. James Palmer’s “The Chinese Think Liu Was Asking For It” is an exception. In this commentary, Palmer, a longtime resident of Beijing and editor at Foreign Policy, argues that many — perhaps even most of the well informed — Chinese living on the mainland either know little or nothing about Liu Xiaobo or view him as a person who made the mistake of going too far, and in a sense wrote his own death warrant.

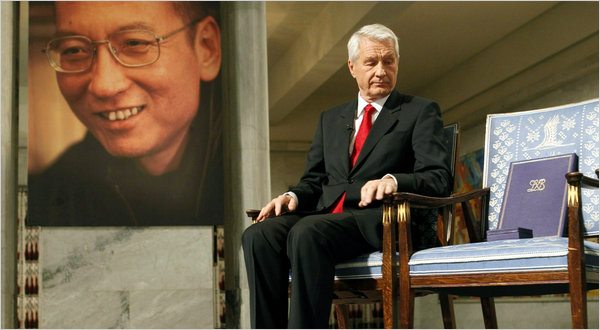

Reading Palmer’s essay, I was reminded of an experience I had attending a speech that the director (now former director) of the Norwegian Nobel Institute gave in Oxford a month after Liu became a laureate. The room was full of students, about half of them originally from China. During the Q&A, the Chinese students burst out with questions critiquing the Committee’s decision. “Why did you pick Liu Xiaobo? Nobody knows him in China,” someone exclaimed. The students felt angry at being told by the West who they should embrace as a Chinese hero.

While many Chinese might react to Liu’s death with the cynicism of these students or the members of the middle class Palmer describes interacting with, I have found that public sentiments towards dissidents in China are often more complex. Not everyone feels either angry disregard or utter indifference toward them. Not everyone, to borrow a phrase from Palmer’s piece, is able to “to sleep comfortably at night” when thinking about what happened to Liu or about the uncertain course of China’s political future.

In my work on China’s critical journalists, editors, and academics over the past decade, I have found that their attitudes towards radical political reform have often been ambivalent in the post-Tiananmen era. This does not equate, however, to apathy or a lack of determination to affect governance change.

“I don’t want to be a dissident, critiquing the system from afar, I want to remain in China and contribute to gradual transformation from within,” a leading public intellectual told me in Beijing in 2009. Despite the tightening of political restrictions under Xi Jinping, this sort of attitude has not disappeared. Those who desire change but steer clear of embracing radical reform sometimes do so for a mix of pragmatic and idealistic reasons—a combination of a healthy survival instinct and a sense that with patience there is a glimmering hope for a better future. Far from excusing the system, the individuals I encounter are often conflicted about it, and channel these conflicts into an intricate dance with the state.

On the one hand, China’s non-dissident but still critical voices, a category that includes some journalists and writers as well as members of some other groups, see partnering with the central state as a way of maintaining a voice in an increasingly unpredictable political climate. The journalists I have interviewed express their critique in what they consider a constructive manner by appealing to the central authorities for policy change and criticizing local officials. In their writing and speaking they often appear as advisers or consultants rather than as direct opponents of the government. When asked whether constructive criticism is a conscious strategy, many say it is an ordinary practice, almost a sub-conscious one.

Other than channeling solution-oriented critiques, journalists and academics of this sort often deploy official policy discourses as a protective umbrella, a political legitimation card. In the past ten years, for instance, they have used the official term “yulun jiandu” or media supervision to justify investigative journalism, to organize conferences on media oversight, and to publish academic articles on media freedom.

Of course, these different manifestations of political pragmatism are in part a practice of self-censorship, but in part they are an attempt at navigating safely in a media system undergoing a major political crackdown. Under Xi, censorship has accelerated and intensified, with the grey space for what I call “guarded improvisation” significantly shrinking. Some journalists, therefore, refer to pragmatic cautiousness as “self-protection,” and regard those that fail at it as impractical, posing risks to themselves, but more importantly to others, with more moderate positions and goals. I haven’t heard direct blaming invoked in Palmer’s piece, but I did witness occasional exasperation at some of these dissident-critics.

At the same time, to the surprise of some Western observers, far from all of China’s critical voices believe in democracy as the best solution for China. The notion of incremental change should not be dismissed simply as reiteration of CCP propaganda. Studies of China’s public intellectuals trace a long cultural tradition of “worrying about China” (a phrase used as the title for a still valuable though dated book on debates among mainland thinkers) and working to improve or fix the system rather than to contest or dismantle it entirely. In post-1990s China, the flourishing of writings about fixing party’s governance has reinforced this intellectual separation between radical and incremental reform. Many journalists I spoke to associated democracy with hope, but also with chaos and uncertainty.

As the possibility for a meaningful political transformation appears to be fading in China (at least in the short term), it seems that pragmatism overpowers idealism in shaping the persisting within-the-system attitudes of many Chinese intellectuals and journalists. Can this pragmatic disposition be broken, or is Liu’s voice one of the last to publicly and consistently articulate a more systematic change?

My latest observations, made in an effort to keep abreast of the trends I analyze in my recently published book on Media Politics in China, suggest that the more the regime intensifies control, the more likely it is to shift some critical voices away from their fluid partnership with the state. Seeing that their position and leverage as advisors to the state has diminished in recent years, some have switched into private enterprises, while others have started expressing more direct critical views in private, and occasionally even on social media. In adjusting their survival strategies, however, most continue to act and want to find a way to remain as insiders. After all, even Liu himself decided to stay in China. Fighting China’s battles can hardly be done from the outside, whether you are a dissident or a more moderate critic.

Maria Repnikova is an Assistant Professor of Global Communication and a Director of the Center for Global Information Studies at Georgia State University. She has written commentaries for venues such as Dissent and Foreign Policy, and her first book, Media Politics in China: Improvising Power Under Authoritarianism, was published last month by Cambridge University Press.