By Ting Guo

With Stranger Things, Netflix produced an original science fiction drama that went viral. But for me, it is also offered up a political drama that illuminated elements of our persistently divided world — and how we might save ourselves from it. Here, in what is admittedly more a series of fragmented reflections than a full account of the series and all of the ways it can be linked to the Cold War and its aftermath, are my thoughts, while watching it in Indiana, reflecting on the present moment and on how different my 1980s was from that shown in the movie and that remembered by American viewers of the same show.

¤

In September 2016, Stranger Things was the thing in the college town in Indiana where I currently reside as a nonresident alien (term c/o US border immigration law, no irony intended). Indiana is also where the show is set. Fictional Hawkins, Indiana, seems to be a quintessential heartland locale, a “normal” American setting par excellence.

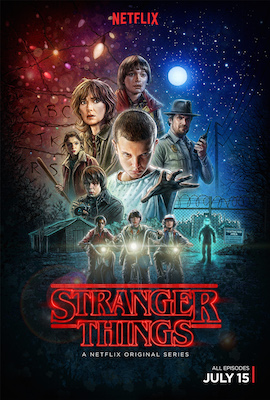

The show’s intro sequence pays homage to the ’80s with synth music typography, and other stylistic elements that evoke the era’s iconic filmmakers. They make us think of John Carpenter (of Halloween fame), Steven Spielberg, and Rob Reiner (in his Stand by Me phase).

In a series of flashbacks, the viewer sees impeccably suited government agents at a neighboring DOE facility conducting sinister experiments on a young girl known only as “Eleven” (affectionately referred to by her friends as “El”). This girl possesses the capacity for telekinesis and can reach a parallel world of alternative reality known as the “upside-down.” She escapes the laboratory and befriends a group of schoolboys, helping find their friend Will Byers who has been kidnapped by a monster from the upside-down.

The kids are the heroes of the show, despite the fact they are often bullied by the “cool kids.” They are kind, caring, loyal to their friends, dedicated to their mission and resourceful in moments of crisis. They represent the humanistic resistance that challenges and mocks scientific and technologically rooted alienation of a sort that grew pronounced in the ’70s and ’80s.

¤

Just like the “other side,” the ’80s was a deeply fragmented world

My Stranger Things appreciation group included friends from Europe, America, and Asia now living in Indiana. They were excited about, even touched by the references to the cult movies of their childhood including ET (1982), the Halloween series, Alien (1986), and The Thing (1982).

These science fiction movies brought familiar memories to me as well, not because I remember watching them as I grew up — none were shown in China in the 1980s — but because I remember the distinctive cultural and political atmosphere of that decade in my part of the world. My memory of that time was colored in a different hue because I’m from the other side, that of the enemy, the dangerous Communist world that the scientists at the lab are working to defeat.

Despite the normalization of US-China relations in 1972, the long ideological divide of the Cold War meant that literature and dramas from Russia, other socialist countries (e.g., Albania and North Korea), as well as from nearby Japan (for different reasons) dominated our cultural imaginaries of the world for almost half a century. The “world” meant mainly just the Communist half, while the “West” was the enemy.

Hollywood productions had only very limited circulation, most viewings were only allowed to certain leaders and units, who had privileged access to what we called “films for internal circulation” (neicanpian 内参片) and “translated films” (yizhipian 译制片). Even in the ’80s, when the government decided to make certain Western films available to the general public, the masses were generally only able to watch old classics, such as Jane Eyre (1943), Waterloo Bridge (1940), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), and the Murder on the Orient Express (1974). The latest Hollywood productions were introduced in the form of carefully organized “Foreign Cinema Weeks,” and rarely did a film from the West show that was not at least a few years old.

My father told me that he could recite the lines from classic cinema. He became a college student after the entrance exams resumed in 1977. Unable to see the movies on the big screen, he practiced his memorization skills by reading the translated scripts in literary magazines. It was from those black and white pages that he constructed the stories so vividly in his colorful imagination. Whenever we watched those films together, he was always in a different universe, a different temporal-space.

Even though I was born in the mid-’80s and grew up in the era of economic reforms when the Chinese everyday ideology had shifted to capitalist, imported music of that era, for me, still meant Soviet tunes such as Katyusha and Evenings in Suburban Moscow (Moscow Nights), not Jefferson Airplane, The Clash, or Toto. Now when I try to hum tunes from my 1980s, a stream of nostalgia embraces me. Although the source is perhaps unfamiliar to my friends, the emotions are similar to what they feel when they hear Stranger Things’ ’80s soundtrack. I remember fondly the comfort these songs once brought my parents in their youth, during turbulent years that saw dramatic social changes.

The 1980s in the U.S. (and Western Europe) was the Decade of Excess, when shiny materialism provided new horrors for science fiction, most notably how those damned by capitalism take revenge at the society that abandons them, hence themes of alienation and otherworldly exploration of materialism. It was also a decade mythologized and characterized by fabled rock stars with outsized and over-the-top lifestyles. At the same time, the U.S. involved itself in activities intended to eliminate or at least check the spread of Communism.

In China, the 1980s was a relatively open era. Following the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution, China opened to the world in 1979. To the North, Gorbachev became the new leader of USSR in 1985 and began some reform. Among those Chinese youths who enjoyed the liberal atmosphere — some took part in the 1989 Tiananmen protest — there is a common remark today that “our Eighties are like the Sixties for Americans.” They express nostalgia for the era of radical thinking, poetry writing, guitar playing, public gatherings, open debates, and above all, the possibility of political transformation.

Though still apart from the rest of the world, the young Chinese of the ’80s closely followed the news of the world, including the “dramatic changes” in Eastern Europe and the fall of the Berlin Wall. I remember reading award-winning school essays from the ’80s with admiration. Their student authors were well versed in international politics and current affairs, debating topics such as On Left and Right or the downfall of Gorbachev.

Mass protests demanding democratization in China flared up in 1989, only to be extinguished. Economic development took the central stage, part of an attempt to dull the memory of as well as repress the spirit for political participation.

An increasing emphasis on Strongman politics and total loyalty to the party leadership means China is drifting farther from the political systems of Western democracies. The short-lived liberal atmosphere of the ’80s has been replaced by heavy censorship and a system that materially rewards political indifference and obedience. Few students now — both American and Chinese — could believe that “absolute power corrupts absolutely” was once a slogan of Chinese students during one of the largest protests for democracy in human history.

¤

The long divide between the U.S. and the Communist world during the Cold War inspired speculation about the technological and scientific experiments conducted in its name, especially the costly efforts by the two superpowers to develop parapsychology and mind-control weapons. The need to stay ahead of the Russians is never far from the surface in Stranger Things. The secret science experiments conducted on El are part of an attempt to create a human weapon capable of intercepting information telepathically from Russian spies.

Some information about the work conducted by the U.S. on these topics is now public. Often unethical and illegal by today’s standards, these studies formed the basis of wartime morale research and consumer behavior studies, as well as begot the ubiquitous social science tool: the focus group. The experiments hoped to build functional machines to access a person’s experiential stream of reality, with the ability to turn this stream into real-time data. Science fiction captures the scientific aims of those government-sponsored experiments to transform “the human.”

Many speculate that the Soviets had similar programs, and Stranger Things reflects such distrust and uneasiness as we wait for the unveiling of the creation of the monster and the upside-down. In doing so, it also pays homage to earlier science fictions films including The Philadelphia Experiment series (1984, 1993). That series was based on a rumored military experiment, said to have been carried out by the U.S. Navy in Philadelphia during WWII, in which the goal was to render a U.S. Navy destroyer invisible to enemy devices.

¤

“Eleven? Are you there? This is Mike.”

As my new friends cheered the songs, the fashion and the cinematic references from their ’80s, they also reaffirmed the historical divide that still haunts our perception of the world today. We too — my old Chinese childhood friends and I — enjoyed pop music as teenagers, but “partying” was not part of life at all, as we grew up with a strict education system that instructed us to be dutiful, hard-working, and well-behaved. We also came of age grappling with a heavy load of homework that prepared us for the fierce competition for almost all kinds of resources at school and at work. Rebellion was reading Nietzsche in the library and greedily glancing at non-curricular literature secreted in the desk drawer while pretending to be doing homework. We are all subject to the historically-situated political arbitraries and embody the unbalanced power structure of the world. Global capitalism gives us the illusion that as long as individuals share the same products, fashion, and lifestyle engineered by the same companies, they are one. However, consumptive habits do not create solidarity. In that sense, it is very similar to the alienation and loneliness that I occasionally feel as a loner in the Midwest.

There is no universal historical memory. The sense of nostalgia and familiarity that Stranger Things evoked for me was the memory of the Cold War and its aftermath, rather than the ’80s, which never arrived in my teens. Even now, as I study Marxism and left-wing political philosophy in a very different light than the Marxist state ideology I grew up with, I would consciously cover the word “communism” or “Marx” when reading them in public in the U.S., worrying that they might cause unnecessary misunderstanding or discomfort to people around me — possibly out of my own paranoia.

How should we understand each other’s different experiences of the same decade? There is so much to learn about the histories through which each other’s experiences were shaped. Perhaps that would be a good point to start. Perception animates all historical imaginaries, and vice versa.

Mike’s resolution to save his friend who was trapped in the “upside down world” is the conscious decision to connect to the other side. Could we do the same? Could we escape the ghost that is haunting us — the ghost of fear and misunderstanding of unfamiliar experience, personal and collective, of history, of the other side?

Ting GUO writes bilingually and divides her time between Shanghai, Beijing, Taipei, and Cambridge, MA. She graduated with degrees in anthropology and religious studies at the University of Edinburgh and previously worked for the University of Oxford and Purdue University.