By Megan Shank

Step out of the Beijing airport, and taste the tang in the air. For the remainder of your time in the capital, it will linger, metallic, on the back of your tongue. Is it burning plastic? Coal? The sweat of migrant workers who have come to chase dreams and money? The boozy breath of corrupt officials? The hot asphalt poured for wide boulevards? The lingering dust of razed neighborhoods, a powdery earthen scent that haunts like an odiferous ghost? Pop music blares. Repairmen bike through neighborhoods with megaphones advertising their services. Garlic hits food vendors’ woks with a sizzle. Amateur opera singers warble in the park. Buses belch fumes. Modern subway doors swoosh open, people smoosh together. Old men with t-shirts rolled up over their bellies sit on stools in alleyways and chat. Young lovers wearing matching outfits interlace fingers and stroll in shopping malls. More than a million smokers could be lighting their cigarettes at any given moment. With enough of a spark, it almost feels like the atmosphere could burst into flames and smolder.

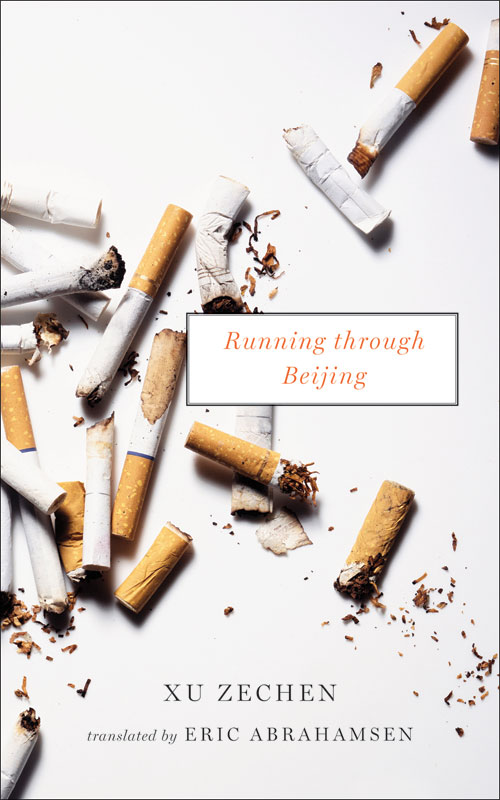

Xu Zechen’s slim 2008 novel Running Through Beijing, recently translated into an English version published by Two Lines Press (2014), transported me back to that city and all its colorful inhabitants. The novel captures the taste and tension of Beijing better than any I’ve ever read. I felt the grit from Beijing’s frequent sandstorms sting my eyes. I savored on my tongue again the spicy mutton of a hotpot joint. Readers will internalize the restlessness and loneliness of young strivers. And Eric Abrahamsen’s translation is so deft, it’s hard to remember that it wasn’t originally written in English. He especially executes slang-filled dialogue with pizzazz.

We meet the raffish Dunhuang on the day he’s released from prison. With the rest of his crew still in jail for selling fake IDs and only a few bucks in his pocket, Dunhuang wanders the streets smoking cigarettes and ducking dirt devils. His only mission is to get back on his feet – and, later, to find a young woman named Qibao for his still imprisoned comrade Bao Ding. Unfortunately, Dunhuang only recognizes the young woman by her ample backside, so he begins a butt tour of Beijing. Xu’s description of this mission seems a lewd wink at what Tolstoy wrote about happy families being all alike: “The majority of asses are unappetizing…The unpleasant ones were each unpleasant in their own way, but the nice looking ones were all similar.”

Dunhuang befriends Xiaorong, a young woman selling DVDs. She is also a transplant but, unlike Dunhuang, has a clearer vision of what she wants for her long-term future: a family and a place of her own back home. The two quickly develop a personal and professional connection – they shack up and Dunhuang begins selling Xiaorong’s DVDs, particularly the highly profitable porn – but other relationships and a crackdown on the illegal DVD market complicate their simple bond, as do several unfolding mysteries of identity.

Dunhuang – whose father randomly chose his name from a newspaper article about the discovery of caves with fantastic Buddhist art – hustles to survive. The book’s title references the German film, Run Lola Run, which makes a cameo. But no matter how fast Dunhuang sprints to deliver DVDs, he doesn’t have much control over the direction of his life. It’s almost as if he were just one speck of dust among countless others blowing, drifting, settling and resettling around Beijing. He meets a diversity of characters along the way. Some seem real to the point of vulgarity; others feel like people from a half-remembered dream. Everyone craves diversion.

Still, Dunhuang experiences a subtle transformation: he gains a new appreciation for art films and increased acumen for business psychology. He’s a highly likable character, and we root for him as he searches for Qibao, negotiates with shifty landlords, navigates his relationship with Xiaorong, and runs into other DVD hawkers who carry children as a defense mechanism against police detainment.

Articles about the Chinese economic boom dominate the newspapers, but Running Through Beijing sheds light on often overlooked underworld sites and transactions – on the karaoke bars that are fronts for brothels, on the counterfeit industry – and demonstrates how the Chinese success story doesn’t extend itself to all players, no matter how great their sacrifices.

The first three-fourths of the book are stronger than its final pages, and its conclusion feels both too tidy and too melodramatic. The author also suddenly abandons Dunhuang for a time to follow Bao Ding, which is jarring. But the writing throughout has great verve and humor. Some lines made me laugh out loud, especially Dunhuang’s ability with insults, calling people cabbage heads, for instance, or saying one woman is “too ugly to argue with.”

During one storm in the book, 300,000 tons of dust descends on Beijing and cakes everything with a yellow film. Much of it comes from Beijing’s construction of buildings and roads. The quest for development and connection has rendered unclear conditions and created an alien landscape. Dunhuang scratches his cell phone number in the sand, along with “DVDs,” and waits.

Megan Shank co-edits the Asia Section of the LARB.