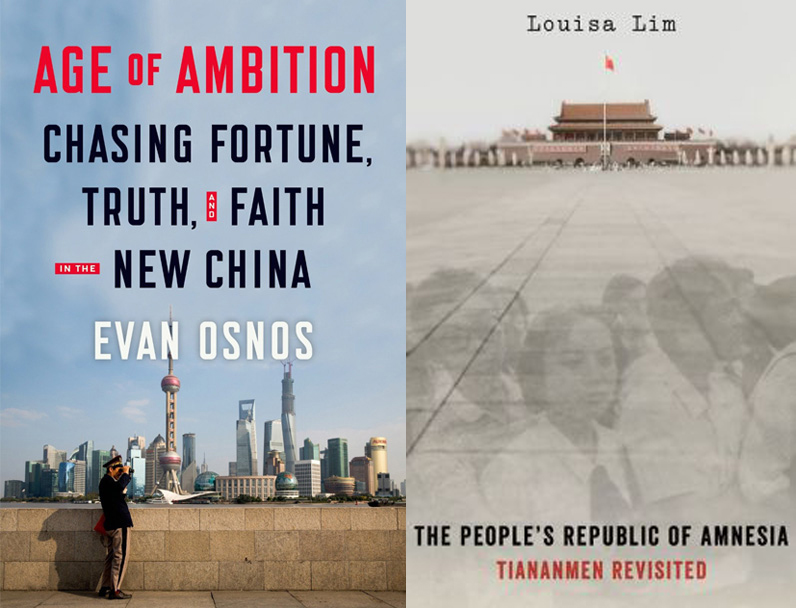

In 2008, I wrote in the Guardian that there had recently been a “notable acceleration” in the frequency with which “illuminating books of reportage” on China had been appearing. It had become routine, I explained, after writers like Peter Hessler and Ian Johnson had come onto the scene, for two or three engagingly crafted books a year to come out that were by journalists who had spent considerable time in China and had sharp insights to share about the country’s recent past and current situation. Still, the year of the Beijing Games was special, since it saw Factory Girls, The Last Days of Old Beijing, Out of Mao’s Shadow, and Smoke and Mirrors all published within a single twelve-month stretch. I continue to admire that quartet of books, but the proximity of their publication dates no longer seems so striking. Why? Because we are mid-way through a three-week period that, when it ends, will have seen the appearance of not just one but two major additions to the list of powerful books on China by talented journalists. I mean, of course, Evan Osnos’s Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China (just out from FSG and garnering very strong reviews, such as this one in the Washington Post) and Louisa Lim’s The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited (which is officially published by Oxford on June 4, but is already available as an e-book, and getting positive assessments as well, such as this write-up in Kirkus Reviews).*

I caught up by email with Osnos and Lim — both of whom will be speaking in Southern California soon and both of whose books are reviewed, in the same article, in this week’s New York Times Sunday Book Review — and they generously agreed to not only answer a question from me, but also to play interviewer as well as interviewee and ask each other one question apiece. My query for each of them is simple: What is in your book that you are proud of having there, but that you had no idea you would deal with when you started writing or planning the project?

Here, in the order in which they will be coming out this way are their answers, with Evan Osnos (who’ll be doing two events at UC Irvine on May 27) weighing in first, and then Louisa Lim (who will be speaking at the Milken Institute in Santa Monica on June 12) going next. After that will come Evan’s question to Louisa and her answer; and then, closing out the interview, Louisa’s question to Evan and his reply.

Evan Osnos: Not long after I started work on the book, a story appeared in the Chinese press about a little girl in southern China who was hit by a van and ignored by more than a dozen passers-by. It was caught on closed-circuit television, and the video, as you would imagine, was wretched. The girl, who was known as Little Yueyue, was hospitalized, while her parents, a young couple who had a small hardware shop, struggled to bear the attention. The story spread rapidly, sparking a large, angry, self-critical discussion in China about how such an event could happen, and what it said about the state of public morality. The debate was impressive in its openness to self-examination, and it showed us how much the Chinese public is struggling with deep questions about the moral basis of the society, the responsibilities that one citizen has to another, and the values that will shape their lives in the years ahead. What surprised me even more, however, is that, months later, when I went down to southern

China and reconstructed the accident, as part of my book, I found that the headlines had missed a critical part of the case. It reminded me of the mythology around the story of Kitty Genovese, a woman whose death in New York in 1964 became as much a myth as a window into the American experience. The story of Little Yueyue turns out to be far more complex and revealing about China than it first appeared.

Louisa Lim: The entire last chapter of my book – in which I uncovered the forgotten crackdown in 1989 in the southwestern city of Chengdu – was a complete surprise to me. I had heard rumors of protests in Chengdu, 1100 miles from Beijing, but I had no idea about the scope of the unrest until I began tracking down eyewitnesses, official Chinese reports and US diplomatic cables. The marches in Chengdu mirrored Beijing’s, but were followed by huge demonstrations on the morning of 4th June 1989 protesting against the killings in the Chinese capital. The marchers carried mourning wreaths and signs saying, “We Are Not Afraid To Die.” The People’s Armed Police tried to disperse the crowds using water cannons and batons, leading to three days of on-and-off pitched battles, during which the police were forced to withdraw to a municipal compound for their own safety. According to official Chinese reports, 8 people were killed and 1800 injured. There was another even more violent incident, in which security forces savagely assaulted ‘rioters’ they had rounded up in a hotel courtyard, using batons to smash their heads. Five independent witnesses described to me how they had seen the bodies of those rounded up being thrown into two trucks “like slabs of meat” or “carcasses” and driven away. Official Chinese accounts said seventy people were detained at that particular hotel, but from this distance, it’s impossible to say what happened to those people, and whether they survived the beatings.

What shocked me most was that an entire chain of events that happened in living memory could be forgotten, from the protests by hundreds of thousands of people to the fighting in the streets, and the barbaric beatings. For those I spoke to, the experience of reliving a trauma that had been suppressed up for so long proved difficult but ultimately cathartic, and later on one of my interviews wrote to thank me, saying, “I lived for years disturbed by the fact that we had witnessed a crime and that it seemed no one else knew about it or cared enough or would risk enough to make sure it was told.”

EO: Louisa, you describe the astonishing story of a mother whose son was killed during the crackdown at Tiananmen Square. A quarter-century later, the spot where he died is now covered, 24-7, by a surveillance camera, which is, presumably, designed to record (and discourage) anyone who seeks to memorialize the death. In our years in China, we watched the rise of increasingly sophisticated and expansive surveillance technology. It’s not unique to China — American and British cities are now covered in cameras — but in China the extent is ambitious, and, most important, the goal of documenting and recording stands in contrast to the determination to forget, which you describe so well. Based on what you learned about the apparatus of amnesia, who in China decides what to remember and what to forget? How much is it based on hard-and-fast principles, and how much is it case-by-case?

LL: That’s a great question. The symbol of the surveillance camera is particularly apt because it represents the asymmetry of information in China; any footage recorded by those all-seeing cameras belongs to the organs of the state (in this case, the security apparatus) rather than the individual. And so the process of documenting and recording history remains in the hands of the Communist party. It uses its propaganda organs — its newspapers, television stations, films, textbooks and its censored internet – to dictate what can be remembered in public. But we have seen cases in recent years where public pressure, especially from the media, allowed public discussion of topics that had previously been taboo, such as the Great Famine of 1959-1962.

There are clear red lines, such as not mentioning June 4th 1989 in the official media, but these sometimes fail because of case-by-case mistakes. For example, there have been several incidents in recent years where references to June 4th 1989 appeared in state-run newspapers because young censors and editors simply failed to recognize Tiananmen-related material in order to censor it. Thus the government’s success in enforcing collective amnesia is paradoxically threatening its own control over information.

What’s sobering is that this year, for the first time, we appear to be seeing a concerted effort to stop private remembrances of Tiananmen. Five of the fifteen people who attended a “June 4th commemoration seminar” in Beijing early in May have been criminally detained. Chen Guang, an artist who was one of the soldiers deployed to clear Tiananmen Square in 1989, was also taken into detention after staging a work of performance art in front of around a dozen friends. That these people who staged small acts of private remembrance should be punished is a clear warning to others.

LL: You preface your book, Evan, with a quote from Confucius: “The commander of a mighty army can be captured, but the aspiration of an ordinary man can never be seized.” Yet as the book progresses, we increasingly see aspirations unrealized, or recalibrated, as they knock up against the reality of life in China. Was there a particular moment during your time in China when you realized that the Age of Ambition was beginning to slide into an Age of Disappointment? And to what extent does the Communist Party itself bear some responsibility for the widespread sense of frustration by raising expectations – for example by making people aware of their rights– and then failing to deliver on them?

EO: It’s an imperfect science, but if I had to identify a point when that sense of disappointment — of narrowing possibility, of constrained opportunity — began to set in, it was probably after the Olympics in 2008. Part of that was, perhaps, inevitable; the Olympics had been such a national adrenaline rush, people had devoted so much political, economic and nationalist energy into it, that there was always going to be a hangover afterward, but then it was aggravated by some iconic issues: the contaminated baby-formula scandal, the surge of corruption and conspicuous consumption that flowed from the 2009 stimulus. To the degree we can generalize, people became aware of political and economic deferred maintenance, and you began to see the collision between the aspirations that had been unleashed, and the state’s limited ability to accommodate them. To me, that is the ambiguous power, and uncertainty, presented by ambition; as a concept, it is inherently hostile to the status quo, and that sets up the tension that we see today inside the country and in its relations with the rest of the world. The Communist Party had no choice but to raise people’s expectations — that was its pathway to survival — but the political and economic inequities in a one-party system, which privileges connected insiders, also limits its ability to deliver on the promise. That is the political puzzle that the Party faces today.

* In fact, if we take books that move between China and other parts of the world and that veer into the realm of fiction, the current three-week stretch is even more extraordinary. In between Osnos’s May 13 release date and Lim’s June 4 one, fall the publication dates of new books by two other people whose past coverage of China I’ve admired: Howard French’s China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa (just out from Knopf) and Adam Brookes’ spy novel Night Heron (May 27, Redhook). Osnos, Lim and French’s publications, incidentally, are all included in “Five Good Books,” a recent Atlantic.com post by James Fallows, who does an excellent job of providing short descriptions of what makes each work special. As for Night Heron, Publisher’s Weekly recently called Brookes a “thriller writer to watch”; watch for a review of his debut novel soon in this publication.